The Battle of the Somme is one of the bloodiest battles in human history. Lasting three and a half months, it was one of the most destructive periods of fighting in the First World War.

Here are some facts about that battle.

Conscripts Versus Volunteers

France and Germany had used conscription before the war. Young men in both countries spent compulsory time in the armed services before returning to civilian life. As a result, there was a large pool of experienced soldiers to draw on when raising the vast armies the war consumed.

The British were in a different position. Not having made use of large-scale conscription, their armies at the Somme were made up of volunteers receiving their first taste of Army life. The majority of the fighting took place between British and German troops. As a result, the Allies were at a disadvantage, fielding inexperienced men against experienced ones.

Colonial Veterans

The British did have experienced troops from their overseas territories. The Indian Army provided professional soldiers. Australians and New Zealanders from the ANZAC fighting force, bloodied by the bitter fighting at Gallipoli, brought experience and courage. Canadians who had served at Ypres meant some men knew what was involved in fighting on the Western Front.

Well Dug in Germans

By the time of the Battle, the front lines in the area had been stable for over a year. The Germans, who were taking a more defensive approach to the Western Front, made good use of the time. They had three layers of trench lines; concrete bunkers dug deep into the ground, and extensive maps of the local terrain. They understood where an attack was likely to come against them and therefore where a British bombardment would fall.

Conflicting Approaches

British tactics at the Somme were a compromise.

By 1916, the British had adopted a French tactic. Troops moved forward in waves, each one moving through its predecessors while they consolidated their hold on the ground that had been taken. In this way, each advance was made by fresh troops. General Sir Henry Rawlinson, whose Fourth Army formed the heart of the British advance, believed the tactic was too sophisticated for his inexperienced troops. He advocated a simpler advance.

Rawlinson differed from Field Marshal Haig, the overall British Commander, in two other aspects of the plan. Firstly, Rawlinson promoted a “bite and hold” approach, making and consolidating small advances. Haig, by contrast, sought a large advance to make a breakthrough. Rawlinson wanted a massive bombardment to soften up the Germans, while Haig thought that would remove any element of surprise.

Haig believed in letting officers on the ground take responsibility for their area. As a result, the Somme tactics were a mixture of Haig’s grand objectives and Rawlinson’s more cautious approach.

Massive but Ineffective Bombardment

Before their attack, the British bombarded the German trenches for a week. Despite Rawlinson’s intentions, this did not break the defenders. The British did not have enough guns. They did not have enough of the right kind of shells, and many turned out to be duds. They did not know about the deep German bunkers, and so did not take them into account.

After all the shelling, the Germans were still ready to defend their trenches.

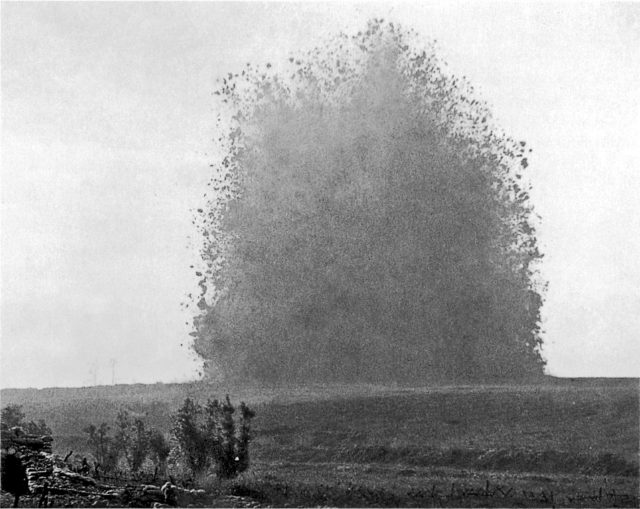

Silence as the Signal

On the morning of July 1, 1916, the British detonated massive explosions under key German positions. When the fallout cleared, British troops emerged from their trenches, ready to advance.

Knowing from previous bombardments that an attack was coming, the Germans recognized the silence of the artillery as a signal that the time had come. They hurried from their bunkers and took up positions to fight.

The Tyneside Losses

As the German guns opened up, the British took devastating losses. 3,000 men of the Tyneside Irish set out during the initial advance. By the end of the first day, less than 50 of them could still fight.

Filming the War

Geoffrey Malins, the first official British War Office Cinematographer, was on hand to film the attack. Before the first advances, he shot footage of the Lancashire Fusiliers crouching in trenches ready to go over the top. He then got back to the lines in time to film the massive mine that was detonated beneath Hawthorn Redoubt, footage that would become famous. Although there to observe, Malins was almost hit several times.

Failing to Take Hawthorn Crater

From the start, Allied advances were disappointingly small. The crater that had once been Hawthorn Redoubt should, in British minds, have been an area of success. After all, the German defenses there had been devastated. However, by the time the British reached the crater, the Germans were defending the other side. The British had to withdraw.

The Tanks

September saw some of the most successful British advances thanks to a new secret weapon – the tank.

Haig had hoped to use 100 tanks in his initial advance in July, but by September he still had less than 50. Of these, 25 made it to the front lines. With their assistance, the British took the village of Martinpuich and overran German positions at the edge of Delville Wood. Despite many tanks getting bogged down and one destroyed, their use was a great success.

Ending It

As the British advanced through a slow, grinding series of assaults, the Germans fell back to their next line of defense. On November 18, Haig decided the attacks had done enough. The next day, he declared the Battle over.

What Was Achieved

Over the course of three and a half months, the Allies took 120 square miles of land from the Germans; an area roughly half the size of the city of Chicago.

Over a Million Casualties

There were over a million casualties in the fighting on the Somme. The Germans suffered half a million, the British 415,000, and the French 195,000. Those who survived, many of them fresh-faced volunteers months before, had become hardened veterans of trench warfare.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.