To the casual observer, it seems that no-one learned anything during the First World War. The same disastrous tactics were repeated over and over again along the Western Front.

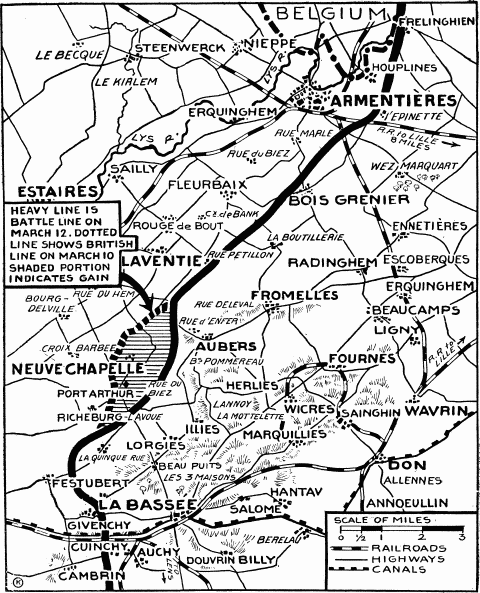

The Battle of Neuve Chappelle was an exception. It took place as the war was stalling in early 1915 and provided valuable lessons to both the Germans and the Allies.

A Large Battle within a Huge Offensive

Neuve Chappelle was one part of a major offensive.

The Germans were digging in for a defensive war. Committed to fighting on the Eastern as well as the Western Front, they hoped to hold the limited battle lines of France and Belgium with fewer men, allowing them to focus on attacking Russia.

The French were far more aggressive. They wanted to retake lost land for both patriotic and practical reasons – some of it was rich in resources valuable to the war effort.

The British were less determined to attack but backed their Allies. With the French advancing into the Woevre plain, they backed them with an assault on the Aubers Ridge.

This British contribution began at Neuve Chapelle.

Shell Shortages and Inconsistent Artillery

By March 1915, both sides were short of shells. Massive numbers had been used, and manufacturing had not yet caught up. Those available were often shrapnel, designed to kill infantry, rather than the high explosives needed to break defenses.

As a result, the bombardment before Neuve Chapelle was carefully planned. Aerial reconnaissance – a new part of war – helped the artillery pick targets.

Despite this, the results were mixed. The shrapnel shells cut much of the barbed wire facing the Indian troops to the south. On other parts of the line, the wire remained intact, ready to entangle men in front of the German guns.

March 10: First Attack and German Response

At 0800 on March 10, after a frantic half-hour of shelling, the assault began. Some troops, such as the 2/39th Garhwal Rifles and 2nd Lincolns, quickly cleared their target trenches. Elsewhere, entire units were mowed down by German fire. Commanders assumed these assaults had succeeded because no men came back. They were all dead or too badly wounded to retreat.

Meanwhile, a barrage pounded the Germans beyond the front line, to stop them entering the fray. This had the unfortunate side-effect of preventing further advances by the successful Allied troops.

The German plan to counter a breakthrough was to consolidate the flanks before filling the gap. They had some success; the 11th Jäger Battalion was putting up stiff resistance on the British left. However, the British persisted, driving back the Jägers.

The Assault Stalls

By 1300, the British had made significant advances with their initial wave of assaults, but orders had not arrived for the next wave of troops. As the soldiers on the front line consolidated what they had, the advance stalled until close to nightfall.

Meanwhile, the Germans brought up reserves.

When the British finally advanced, they found German strong points instead of the open ground they had expected. German artillery disrupted attempts to organize another attack. The advance stalled.

March 11: Renewed Attack

The next morning, the British went back on the offensive.

This time things were tougher. Thanks to the advances of the previous day and the digging in that had followed, the trench lines had moved. Information previously used to direct the artillery was out of date. Fog prevented them from seeing how the land now lay. Precious shells were spent pounding empty fields.

On the front line, information was also a problem. The 1st Grenadier Guards misidentified their location, leading to more wasted artillery. Units failed to communicate with those beside them. With orders coming separately from the Indian Corps and the IV Corps, there was little coordination. Information had to pass all the way up the lines and then back down for it to spread.

Amid this chaos, the Germans held up the British. As night fell, their VII Corps joined the front line, to provide further resistance.

March 12: Both Sides Attack

On the third day, both sides planned to advance.

The Germans seized the initiative. An artillery bombardment at 0430 was followed by an infantry advance at 0500. Their shelling was no more effective than the British had been the day before. With the British troops well dug in, the Germans faced strong resistance and were cut down.

Now the British began their last great assault of the battle. It was another uncoordinated affair. The 2nd Scots Guards, having taken a German position, had to withdraw after being shelled by their own side. It took four hours for news to reach headquarters that the German advance had stopped and they could launch a full offensive. The artillery, still reorganizing after the previous day, could not manage full bombardments until well into the afternoon.

Advances were made, and more ground was taken, but the skies were overcast, and dusk came bringing an end to the attack. The British secured what they had taken.

The Battle of Neuve Chapelle was over.

Lessons Learned

Several lessons were learned at Neuve Chapelle, in particular by the British. Some were useful, others counter-productive.

The blocking barrage was effective and would be used almost obsessively, more usefully on some occasions than others.

Need for light machine-guns to support the advance was recognized, leading to the development of the Lewis gun. It weighed less than a third of the Vickers Maxim.

One big problem was the failure of communication, partly organizational and partly from cut telephone wires. It was something both sides would grapple with throughout the war.

The highest profile lesson, spread by General Sir John French, was that the British had not had enough shells. In fact, shelling had sometimes been counterproductive, and more shells would not have helped. The belief they would, however, took hold of the public imagination, helping to bring down the government two months later.

For better or for worse, Neuve Chapelle was a learning experience.

Source:

Martin Marix Evans (2002), Over the Top: Great Battles of the First World War.