In the 1950s, the Jet Age was in full swing, and manufacturers were looking to make the biggest advancements with this new technology. High-performance internal combustion engines had dominated in the 1940s, but the jet engine, which was developed slowly at first, had virtually revolutionized the aircraft industry overnight once engineers saw its potential. This prosperous post-war era is considered by many to be the golden age of aircraft design, as it seemed no idea was too outlandish.

During this time, the U.S. had no shortage of weird and wonderful experimental aircraft all utilizing this new technology, like the XF-84 “Thunderscreech,” the Lockheed XFV, and the VZ-9 Avrocar.

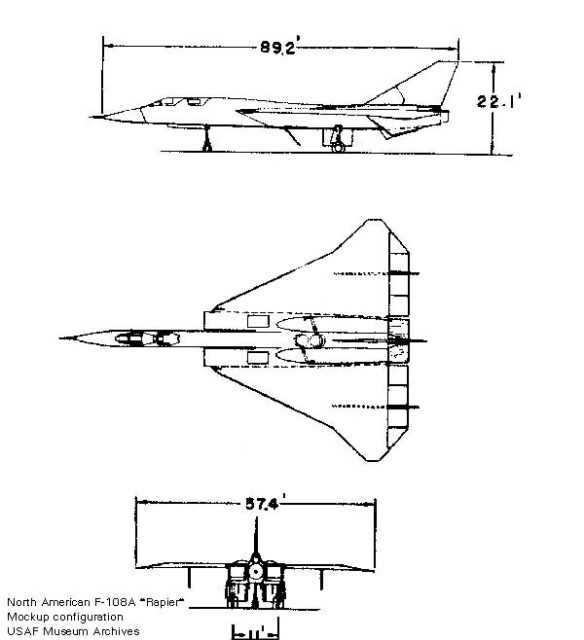

One of the more extreme aircraft to be proposed during this period was the XF-108 Rapier.

The XF-108: an interceptor for the ages

The aircraft was designed by North American, the same manufacturer who brought the world the P-51 Mustang. If the XF-108 had actually flown, it would have been one of the highest performing and most advanced aircraft of its era.

It was born out of a need to protect the U.S. against the threat of approaching Soviet bombers armed with nuclear weapons if a war between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. ever broke out. As an interceptor, the XF-108 was designed for range and extremely high speeds, so it could greet and shoot down Soviet bombers long before they were over U.S. territory.

Designers had originally hoped the XF-108 would be able to accompany the even more advanced XB-70 Valkyrie bomber, which was being developed by North American, too. At the time, the XB-70 was assumed to be too fast to intercept, but the addition of a nimbler but equally fast fighter on its missions would have improved its chances of survival even more.

However, designers were met with engineering challenges that were simply too much to overcome with the technology available to them, so this idea was eventually dropped. Despite this, North American planned to use the General Electric YJ93 engine in both aircraft to reduce production and development costs.

The XF-108’s cutting-edge design

Speed was the name of the game for the XF-108. It was powered by two of the aforementioned General Electric YJ93 engines that produced 29,300 pounds of thrust each, with afterburners. This is more than the F-15 Eagle or Eurofighter Typhoon. With this power, the XF-108 was expected to reach a speed just shy of 2,000 mph.

To detect approaching bombers, the XF-108 was equipped with AN/ASG-18 prototype radar. It was paired with an infrared search and tracking system and was highly advanced for the time. This device had a range of up to 300 miles and could accurately detect bomber-sized targets at about 100 miles.

The drawback to the radar was its size, as it weighed nearly 1,000 kilograms.

For shooting down bombers, the XF-108 was armed with three GAR-9 missiles. These were designed alongside the AN/ASG-18 radar and had a range of about 100 miles at a speed of over 3,000 mph. The range of this missile was so great that it had its own radar-guidance system installed so it could still reach its target while out of range of the aircraft it was launched from. They were stored in an internal bay on a rotary launcher.

The interceptor was incredibly large relative to other aircraft at the time. At 27 meters long, the XF-108 was longer than the F-22 Raptor and even a B-17 Flying Fortress.

The XF-108 was shaping up to be a truly deadly aircraft, and one of the most advanced of the era. However, it never got to fly, as it was one of the many victims of the intercontinental ballistic missile.

Cancelation

Both the U.S. and Soviet Union had been hard at work developing intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) since WWII, having been heavily inspired by Nazi Germany’s V-2 rocket. ICBMs were much better at delivering a nuclear weapon than bombers because they were easier to hide, able to reach their target within 30–40 minutes, and able to reach such high speed (around 4 miles per second) that interception would be impossible.

The Soviets achieved the first successful ICBM launch in August 1957 with the R-7 missile. This moment immediately changed the priorities of nations around the world. The ICBM simply rendered the bomber obsolete, and therefore an interceptor to shoot down the bombers was no longer needed.

The XF-108 program was canceled just two years after the launch of the R-7. Only a mock-up had been built.

More from us: From DC-3 To RV — Air Force Vet Gives A Plane A New Life As An RV

The development of the XF-108 wasn’t completely wasted, though. North American managed to use much of what they had learned from the XF-108 in the A-5 Vigilante, a carrier-based bomber that has a clear lineage to the XF-108.

The AN/ASG-18 radar would later be used in the YF-12 program, and the GAR-9 missile would eventually mature into the AIM-54 Phoenix that was paired with the F-14 Tomcat.