A World War II survivor, Mac Colquhoun, recalls strolling the grounds of his prisoner-of-war camp with bags of dirt hidden beneath his clothing. The 98-year-old demonstrates the way he hid the bags of dirt under his pants leg. The reason he hid dirt? That is how Allied prisoners got rid of the dirt left over from the escape tunnel they were digging.

Colquhoun is originally from Saskatchewan, Canada. He recalls leading the life of a healthy farm boy before signing up with the Royal Canadian Air Force in the 1940s. He remembers that his bomber was crippled by heavy flak in 1943. His lieutenant ended up parachuting into a field; another crew member landed safely, one, unfortunately, died during the escape, and the rest of the seven men crew were never found. Colquhoun ended up in a POW camp Stalag Luft III in Sagan, Poland.

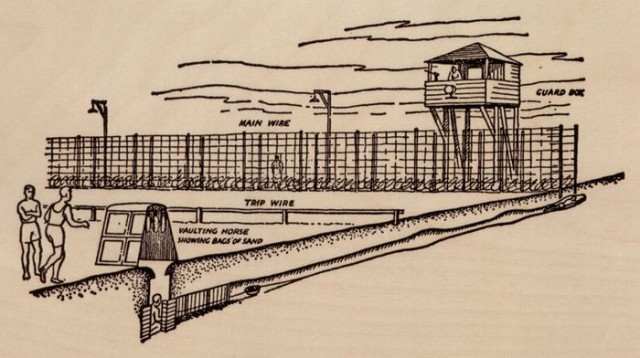

It was in this camp that the famous “Wooden Horse” escape plan took place. To stage this escape from the camp, the prisoners used plywood from Red Cross crates to build a gymnastics horse that was put out on top of the tunnel being dug in the prison yard each day.

One or two prisoners would be hidden in the horse; they would continue digging until time to remove thehorse for the day. They would cover the ground where they had been digging; others would remove the loose dirt from the excavation and stuff it into bags hidden under their clothes, secretly dispersing it whenever and wherever they could.

Colquhoun’s role was to haul the extra dirt away, and the memory of it is clear to him. The trickiest part was in hiding the tunnel’s yellow sand, which stuck out in sharp contrast against the brown topsoil of the camp. The prisoners hid a lot of the yellow sand beneath vegetable gardens; some sand was stored in a roof, and other had been poured down a hole in a theater stage. To disperse the rest of the dirt inconspicuously, other prisoners would follow the dirt dispenser who had sand trickling down his pants leg, kicking up the soil around him.

After the hard work of the prisoners, three were able to escape through this tunnel. To choose who got to escape, they decided that the ones who spoke German were to leave first. That way, those who spoke the local language and had a better chance of making it home. These three eventually did end up making it back home to Britain safely.

As for “Great Escape”, Colquhoun said that this idea was hatched in a different part of the camp just across the wire from his. There were 76 prisoners who managed to escape. However, 73 were captured and out of these, 50 were executed. Six of those 50 were Canadians. Colquhoun had heard that Hitler decided himself which escapees would be killed. There was an air raid that disrupted this escape plan, which Colquhoun states was a good thing, for if they had all escaped, they would have been executed for sure.

Two years after having been shot down and as Russian soldiers were nearing Sagan, Colquhoun was moved west to another German camp. Colquhoun recalls that this was in winter; he and his fellow prisoners did not have any proper clothing against the cold. One of his bomber crew members actually froze to death during the move, the Times Colonist reports.

When it came close to the end of the war, the prison camps’ guards started disappearing. That is when Colquhoun and his friends took matters into their own hands. They stole a car and drove it 200 kilometers to an airport that was being used by the Allies. The only thing they could do to pay for tickets to get on the plane was use the car they drove as leverage. Thankfully, the two men made it to England without any issues. Later that year, Colquhoun was back in Canada. He started a family and had a 25-year career as an accountant.

In his room where he was interviewed hangs a picture of the 50 men who were executed after the Great Escape. Colquhoun now lives in a residence hall with almost 229 other Veterans.