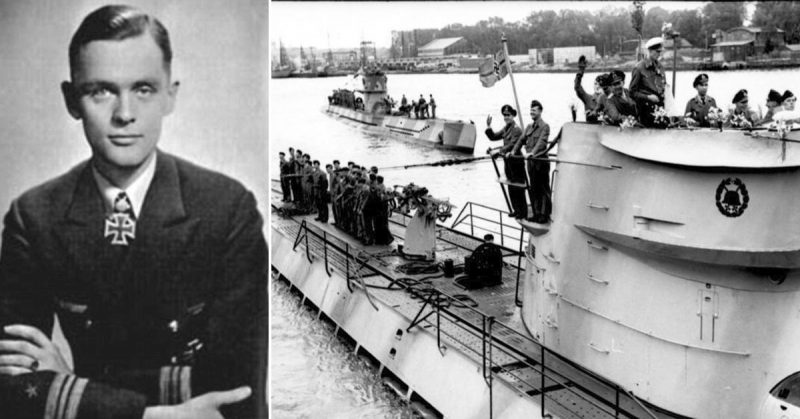

The list of surviving World War II veterans is getting shorter and shorter. On June 9, 2018, Korvettenkapitän Reinhard Hardegen, the last surviving U-boat Commander of the German Navy, died in the German city of Bremen at the age of 105.

Hardegen is credited with sinking over twelve American ships, eight British ships, a Norwegian steam merchant ship, a Portuguese steam merchant ship, a Panamanian motor tanker, an unarmed Latvian steam merchant ship, and a Swedish motor merchant ship.

Originally, Hardegen had served in the Marineflieger (Naval Air Force), training as a pilot. An airplane crash in 1936 left him with severe injuries and a shorter leg, stomach problems, and chronic diphtheria. However, with great determination, he was able to get appointed to U-124 under Korvettenkapitän Georg-Wilhelm Schulz as First Watch Officer.

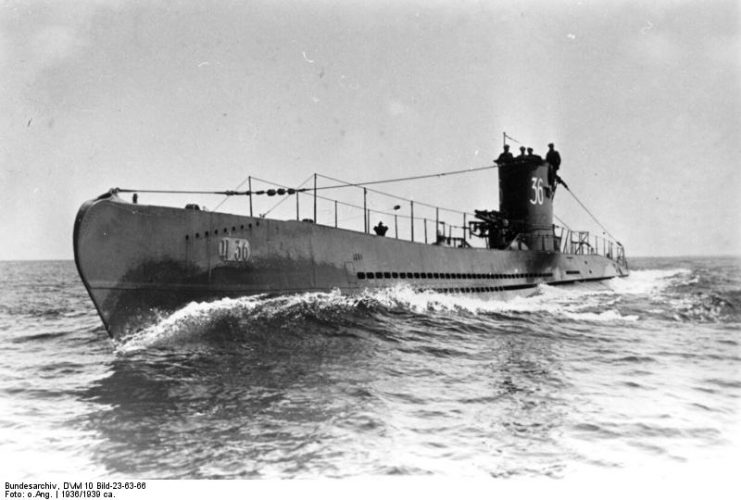

In 1940, he received his own command on U-147, which formally went into service in February of 1941. The next month, the U-147 sank the Norwegian steamer Augvald. In May of 1941, Hardegen took command of the U-123 and sank five ships over that summer.

In December of 1941, shortly after the United States entered World War II, the U-123 and four other U-boats were sent to the East coast of the United States to attack freighters sailing to Europe in Operation Paukenschlag (Drumbeat). The purpose was to demoralize American citizens and put a stranglehold on supplies to Great Britain.

Hardegen made his way to the Canadian coast, sinking more ships on the way and earning himself the Knights Cross in the process.

With only a tour book and basic map of the East Coast, Hardegan was instructed to attack ships off the coast of New York and move southward to North Carolina, continuing to attack until it was time to return to occupied France for refueling.

The Americans were still stunned by the attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese and gave little thought to Germans on the East Coast. There were no blackouts or radio silence and ships without destroyer escorts were sitting ducks.

The British, having been involved in the war since 1939 when Hitler attacked Poland, had a tracking system for U-boats already set up in the town of Bletchley in Buckinghamshire, England, where the World War II codebreakers made their home.

U-boat tracker Rodger Winn knew of Hardegen and his determination and had tracked the group of U-boats as they crossed the Atlantic. Winn urged the United States to prepare for attacks, but Rear Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner, the director of War Plans in Operation refused to utilize the U.S. Office of Naval Intelligence because of internal problems caused by too many egos. Captain Alan G. Kirk, the head of the ONI was so disillusioned by the internal problems he resigned in October of 1941.

In January of 1942, the U-123 was off the coast of Cape Cod listening to the wireless transmissions of both military and merchant ships. The British freighter, the Cyclops, had begun its journey back home when it was attacked by Hardegen. After being hit on her port side with a torpedo, she sank within five minutes.

Making its way into New York harbor, the Norwegian tanker Norness was on the way to Halifax loaded with petroleum when U-123 attacked. It took five torpedoes to sink the ship, in water that was so shallow that parts of the ship never submerged. Still the U.S. Navy did not react.

A few days later U-123 had made its way south to Cape Hatteras, sinking passing ships along the way. Once in southern waters, Hardegen torpedoed six more ships before turning for home and leaving more sunken ships in its wake.

In March, U-123 returned to the waters off the coast of Virginia. Hardegen destroyed two tankers and attempted to sink the USS Carolyn, a heavily armed ship camouflaged to appear as a freighter. After shooting a torpedo that revealed the ship’s armament, U-123 turned to flee.

The Carolyn dropped depth charges and sent shells flying toward the submarine but failed to hit it. Hardegen took advantage of the opportunity and sent a torpedo into the ship’s engine room, exploding the ship into pieces.

Hardegen was finding more resistance than earlier in the year but still managed to sink several more ships, including the Gulfamerica, a tanker on its maiden voyage off the coast of Jacksonville, Florida.

As United States destroyers began to succeed in destroying the U-boats, Operation Drumbeat was wound down, and the surviving submarines headed for home in April.

After the war, Hardegen was a senior executive in a marine oil company and served in Bremen’s parliament. He wanted it known that he was not a Nazi. He disagreed with some of Hitler’s policies and criticized him to his face, an extremely dangerous thing to do. Hardegen claimed he fought for Germany, not Hitler.