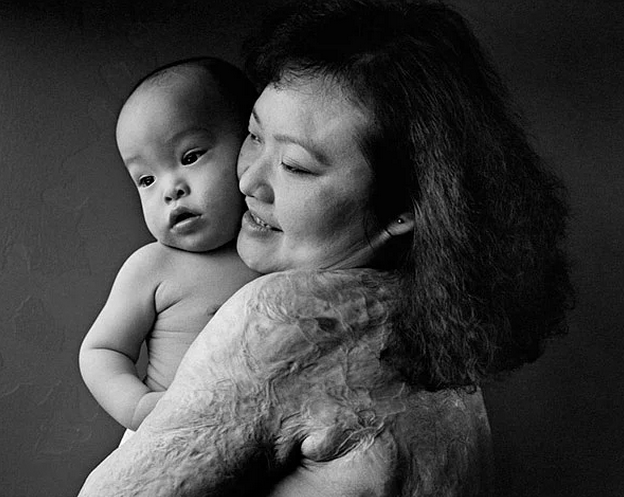

Kim Phuc was bitter and full of hatred for 10 years after the napalm bombs were dropped on the Vietnamese temple where she was taking refuge with her family. Covered by scars on over 65% of her body, she was in terrible pain and believed no one could love her. “I had a lot of physical and emotional pain,” she says.

She finally found “peace and joy” at the age of 19 when she converted to Christianity. “It changed my life. My heart healed,” states Phuc, who is now 54.

Over the last two decades, Phuc has been travelling the world to tell her story of hope. The emotional scars healed decades ago. The physical scars are healing now as she undergoes laser treatments.

Her conversion to Christianity was only the first step to healing for her. She converted during a difficult period when the Vietnamese government made her quit medical school to give media interviews. This nearly ended a dream she had since shortly after the attack – to be a doctor. She was always grateful to the doctors and nurses that helped her through 14 months of agonizing treatments, some of which were so painful she passed out during them.

“They were there every moment I needed them,” she says. “I said, ‘OK. I want to be like them.’ I can help myself and another who needs help just like me.”

After leaving the hospital, she went back to her village to find it was nearly completely destroyed. Relatives had been sent to “re-education” camps and returned “mentally damaged.”

Not being able to go to med school and become a doctor was devastating. “I stopped wanting to live… I doubted God.”

As a result, she went to the library and read every religious book she could find. She hoped to find the answer to her questions: Why me? Why do I have to suffer? She says, “I thought no one would love me and I’d never have a normal life.”

That’s when she found the New Testament of the Bible and the Christian belief in forgiveness.

“No way. How can I forgive the people who did this to me?” she recalls thinking as she read the verses. It took her a long time to reach a point where she could.

In 1986, the Vietnamese government finally allowed her to move to Cuba and attend medical school. There, she met Bui Huy Toan from North Vietnam and fell in love. He told her that her scars made him love her even more.

There was more disappointment when she learned that her injuries left her without the physical strength to become a doctor. Fortunately, she now had someone to share the pain with. They married and then defected to Canada five years later. Over the years, their family grew to include two sons.

Phuc started a foundation in 1997 in order to help children who are victims of war. She also became a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador for peace. Ever since, she’s been travelling and telling people about love, hope and forgiveness as she shares her story.

Some, however, are not ready to hear such a radical message. Once, after speaking in Ohio, a woman who had lost a daughter in the Oklahoma City bombing confronted her angrily. Phuc invited her to dinner.

“[The] whole dinner she was upset about my philosophy. I said, ‘You know what? I can’t change what happened in the past. I was nine. I got burned so badly, but what can I do? I never live in the past. I learn from it.’”

She was able to reach the woman, who agreed to try to forgive.

Another time, she was visiting a burns unit in Uganda. It was her first time in a burn unit since she’d left the hospital twenty years before. “It brought me back to the burn unit I was in. So painful. So scary.”

During the visit, she met a woman whose husband threw acid in her face. “She said, ‘Kim, you talk about forgiveness. How can I forgive my husband who did this to me?’”

Phuc told her that she had had the same question “for a long time in my life.” But she had learned “through experience God loves me for who I am, not how I look. I trusted God to bring the right people to my life. And He did.

“’But trust God. If you are true, a true friend will come into your life.’”

“The nurse saw me later and said, ‘Kim, I’m so thankful you spent time with her. After you left she stood up. She’s smiling. You gave her hope. She doesn’t want to die anymore.’”

These stories are what sustain Phuc. She is not paid by her foundation. She and her husband live off his salary as a social worker.

The physical scars are healing now. The emotional scars are already gone. “I learned how to move on, how to cope, and I’m thankful,” she says.