The Medal of Honor is the highest military award for bravery that America can bestow upon its soldiers. The medal is awarded personally by the President of the United States, and since its inception in 1863 it has been awarded on only 3512 occasions – around half of those were during the American Civil War.

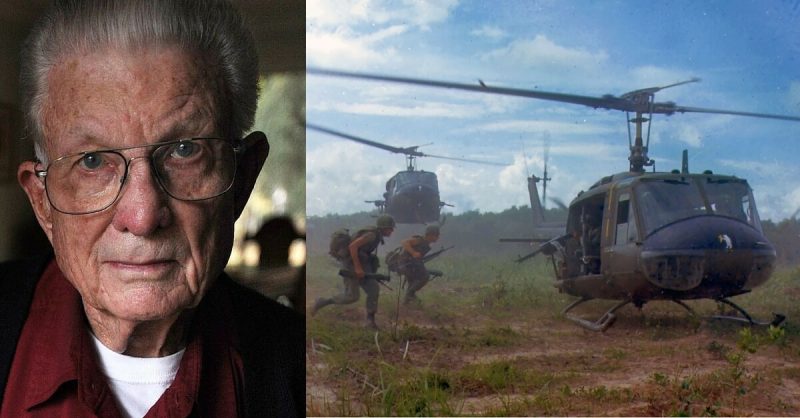

The US Secretary of Defence has recently approved the award of a Medal of Honor, and once it has been endorsed by Congress, then President Obama will put his signature on a document to make it official. The medal will go to Vietnam veteran Charles “Chuck” Kettles from Michigan who, on 15 May 1967, carried out an extraordinary act of bravery on the field of battle. For this action he has was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross in 1968.

It wasn’t until 2012 that a local campaign was launched by William Vollano, a coordinator with the Veterans History Project, for Kettles to receive the Medal of Honor, according to Peters’ office.

His citation for the Distinguished Service Cross:

For extraordinary heroism in connection with military operations involving conflict with an armed hostile force in the Republic of Vietnam, while serving with 176th Aviation Company (Airmobile) (Light), 14th Combat Aviation Battalion, Americal Division. Major Kettles distinguished himself by exceptionally valorous actions on 15 May 1967 while serving as aircraft commander of a helicopter supporting infantry operations near Duc Pho. An airborne Infantry unit had come under heavy enemy attack and had suffered casualties.

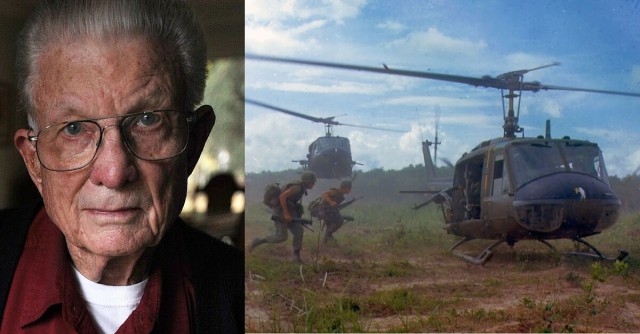

Major Kettles immediately volunteered to carry reinforcements to the embattled force and evacuate their wounded from the battle site. Although friendly artillery had pounded the hostile positions, the enemy was well entrenched and fighting fiercely. Major Kettles led a flight of helicopters into the landing zone through a savage barrage. Small arms and automatic weapons fire raked the landing zone and inflicted heavy damage to the ships, but Major Kettles refused to leave the ground until all the craft were loaded to capacity. He then led them out of the battle area. He later returned to the battlefield with more reinforcements and landed in the midst of a rain of mortar and automatic weapons fire which wounded his gunner and ruptured his fuel tank.

After leading more wounded aboard, he nursed the crippled craft back to his base. He then secured another ship and led a flight of six helicopters to extract the Infantry unit. All but eight men had been loaded when Major Kettles directed the flight to take off. Completely disregarding his safety, he maneuvered his lone craft through a savage enemy fusillade to where the remainder of the Infantrymen waited. Mortar fire blasted out his windshield, but he remained on the ground until the men were aboard.

The enemy concentrated massive firepower on his helicopter and another mortar round badly damaged his tail boom, but he once more skillfully guided his heavily damaged ship to safety.

By the time he returned to the United States in 1970 Major Kettles had flown more than 600 missions in total and gained 27 air medals. He served at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonia in Texas until his retirement from the army in 1978.

Now, 48 years after the events described here he is about to receive his country’s highest possible award for valour. Modest about his achievement on that day, Kettles says that the fact the names of the men he rescued are not on the Vietnam Memorial wall in Washington DC is “enough gratification”.