Governors and representatives of 10 states in the western US met on April 7, 1942, with Milton S. Eisenhower, the director of the War Relocation Authority (WRA) and other federal officers. The meeting, held in Hotel Newhouse in Salt Lake City, Utah, was held to discuss relocating Japanese from assembly centers to camps in the badlands of each state.

Milton Eisenhower was an educator and a brother to the future president Dwight D. Eisenhower. He reminded the attendees that two-thirds of the 120,000 Japanese citizens that had been detained were Japanese-American citizens and that one-fourth of them were under the age of 15.

Eisenhower said that he did not want just dump people into the region indiscriminately. He had a program in mind that would put people to work in useful public tasks like farming, manufacturing, and public works. He had in mind for the camps to be self-supporting.

Eisenhower pressed on the officials that these were professionals – lawyers, doctors, domestic workers, college students, etc. They wanted to keep busy and be useful.

Four months after Pearl Harbor, however, hysteria and racism won out over Eisenhower’s desire to handle the situation in “an American way.”

The Idaho governor, Chase Clark, called the Japanese “rats” and agreed to allow them in his state only if they were guarded by the military in concentration camps. The Idaho attorney general wanted to “keep this a white man’s country.”

The governor of Wyoming, Nels Smith, believed there would be Japanese people hanging from every tree. Herbert B. Maw, governor of Utah, complained that if the Japanese were too dangerous for the West Coast, then they were too dangerous for Utah.

Only Governor Ralph Carr of Colorado was the only one to speak on behalf of the Japanese. Stating that he grew up in a town and had experienced racism firsthand, finding it shameful and dishonorable. He simply stated, “If you must harm them, you must harm me.”

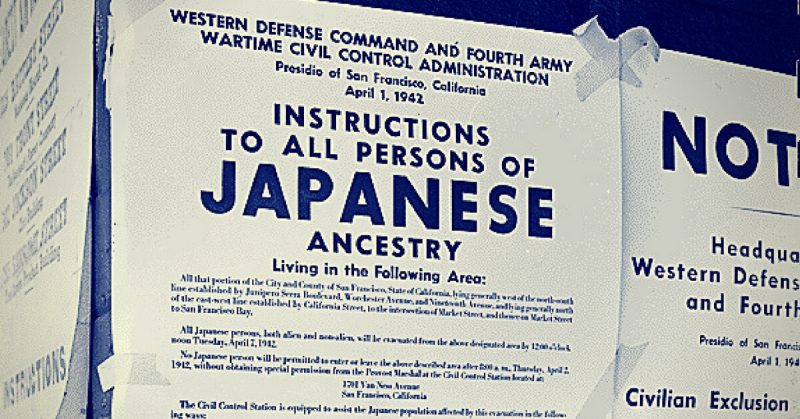

They used the 1940 census to find Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast and built ten inland internment camps. There was no guarantee of due process of law for anyone taken to the camps.

Harry J. Ueno was born in the US. He was sent to Japan to live with his grandparents while his parents farmed in Hawaii. When he was 16, he returned to the US and began working at a Washington lumber mill until the early 30’s. At that time, the mill unionized and the Japanese workers were forced out.

He moved to San Francisco, married and raised three children (who all enlisted in the US military) while working as a buyer/manager for fruit markets that serves the upper class.

On May 10, 1942, he was picked up and sent to Manzanar. He worked as a cook in Block 2. While there, he established a mess hall workers’ union, kept records, and voiced complaints about food shortages, pay inequity and corruption in the camp administration.

Ueno was suspected of joining a group of men that beat up a suspected FBI informer. He was sent to the Dalton Wells isolation center. A riot occurred at Manzanar where guards shot and killed two inmates.

Dalton Wells was a former Civilian Conservation Corps camp. It was rundown, primitive and isolated. Family contact was not allowed. Mail was censored. Prisoners were harassed, pressed into getting in fights and then arrested for it.

The camp director told Ueno that anyone could die there and their body would never be found, The Salt Lake Tribune reported.

Ueno was put in the camp jail for talking to other prisoners. On April 27, 1943, Ueno and other prisoners were locked in the back of a 4×6 foot box, loaded on a flatbed truck and taken to another isolation center and then to yet another one. It was months before Ueno could make his way home.