The Munich Crisis in 1938 made Martin Davies, who worked as an assistant at the National Gallery in London, an extremely nervous man. He was worried that the valuable artworks in his care would be stolen or destroyed if war broke out and, because of this, he started looking for places to hide the museum’s paintings away from possible harm.

So in 1939, a number of paintings were removed from London and secreted at various remote locations in Wales, including three stately homes, the National Library in Aberystwyth, and the University of North Wales. It was Davies’ idea and a fairly good one at that, no enemy would think to search in such locations. The change was not without its issues though, for example Caernarfon Castle was used as a combat outpost and naturally became a bombing target for enemy forces. In one of the stately homes, the under-floor central heating pipes where a nightmare for the museum conservationists. The stashed paintings needed to be stored in a carefully controlled climate to prevent them deteriorating.

The only way to maintain the humidity levels for the delicate painting’s needs was by hanging up wet towels. The idea was ridiculous for artwork that was so prestigious, so it became an important mission to relocate these paintings to a place better suited to their standards. But 1940 came, and the Germans were nearly at the doorstep of London. People feared what would become of these national treasures if they fell into the hands of the Third Reich. It was said the art pieces would be sent privately, and in a hidden manner, to Canada for safe keeping, but certain government officials did not want that to happen. These government figures were scared that enemy boats would attack the transport ships and reap the rewards for themselves, or leave them to perish in the depths of the ocean. They said that hiding the paintings in barren caves and mountains would be a better idea than having the paintings away from England.

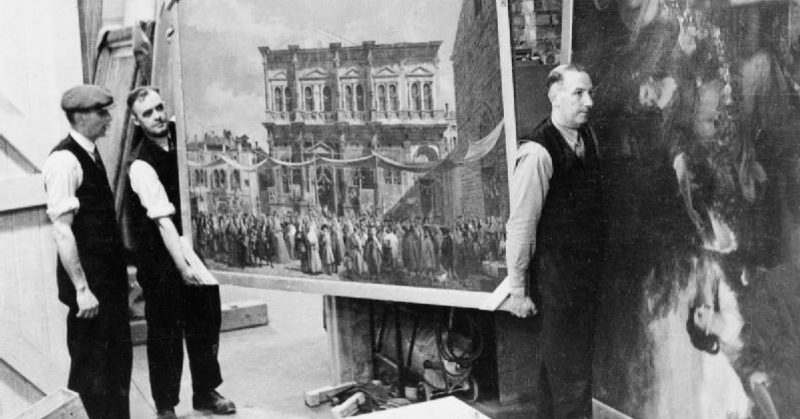

Soon after, a disused slate mine at Manod in Blaenau Ffestiniog, North Wales, was found to be suitable. It was quite a large mine, giving enough room for the entire collection of paintings to be stored, away from the face of danger. Once the site had been prepared, which included shifting several thousand tons of rock and creating special areas in which the environment could be carefully controlled and the paintings monitored, the National Gallery collection was carefully trucked to the site. This upped the gallery’s prestige drastically. Moving the masterpieces away from London proved to be a smart decision in this peculiar circumstance; the gallery site in Trafalgar Square was hit nine times during air raids.

It’s possible to view the artworks through the National Gallery’s online picture of the month, a modern day nod to the war time tradition of returning one picture to the London gallery every month as a boost to morale. One more long-term effect of the collection being kept in Wales was that the paintings were featured and detailed in catalogs for the first time. This pleased the keen public and art fans very much, as they could finally witness the beauty of the collection in print.

It was the best decision to relocate the paintings, otherwise all of them could have been destroyed. Martin Davies was soon promoted and moved up the ranks to gallery director. Being solely responsible for these paintings was a big undertaking for Davies, and for his efforts he also received a knighthood. He lived up to his potential, producing meaningful literature on the artworks for all to enjoy and be influenced by. It would have been a disaster if these illustrious works of art were left in London to potential destruction, we would have never gotten Martin Davies’ fascinating texts and may have lost the beautiful paintings themselves.