A recently translated book is likely to put to bed the rumors regarding Hitler’s survival at the end of WWII. The book is the memoir of a Russian translator who worked in Berlin during the fall of the city, and one of the tasks she was given was to prove Hitler’s death.

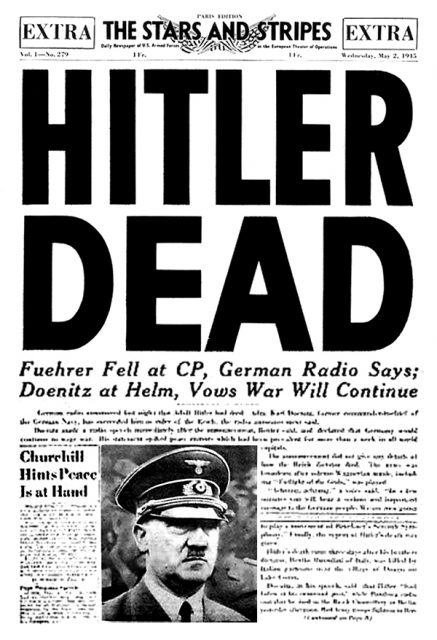

Toward the beginning of May 1945, Belin was in chaos with gunfire crackling as the Red Army mopped up the last of the German forces, and Russian troops celebrating amongst the rubble littering the streets. Everyone was looking forward to the coming peace and word had reached Allied High Command that Hitler had killed himself on the 30th April 1945. However, there was no proof of this fact.

Work on rounding up the German leaders progressed, and many of the team members were translators who worked with the intelligence community. One of these translators was a young Russian lady by the name of Yelena Rzhevskaya. Her normal job was translating the transcripts from the interrogations of captured German officers, and there seemed nothing strange when she was summoned to the office of her commanding officer, Colonel Gorbushin.

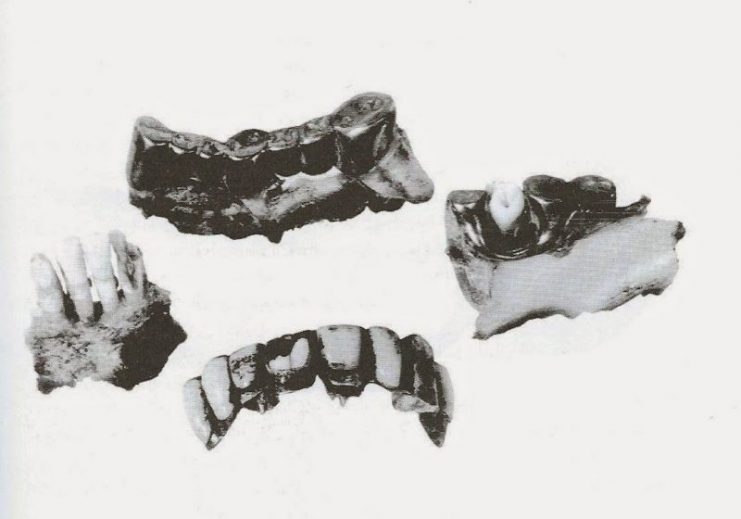

When she entered the room he handed her a box. There was nothing particularly special about the dark red box; it was a little beaten up and had a soft, satin lining. However, the contents of the box took her back as she found it contained a set of teeth. Colonel Gorbushin told her that they were supposedly Hitler’s teeth and she was to guard them with her life! She was about to embark on a very strange assignment.

Although German radio had reported that Hitler had killed himself, many in the Allied leadership did not believe it and were certain that he had escaped Berlin and was on his way to South America in a submarine or he was headed to the border and anonymity amongst Nazi sympathizers living outside of Germany. Ms. Rzhevskaya was tasked with using the set of teeth she’d been given, which had been found in the grounds of the Reich Chancellery, to determine whether or not they did, in fact, belong to Hitler, once and for all proving that he was dead. She was completely surprised, and, staring at the grisly fragment contents of the box, asked her superior why she had been chosen for this task. He flippantly said that as she was a woman, they decided she was less likely to get drunk and lose them!

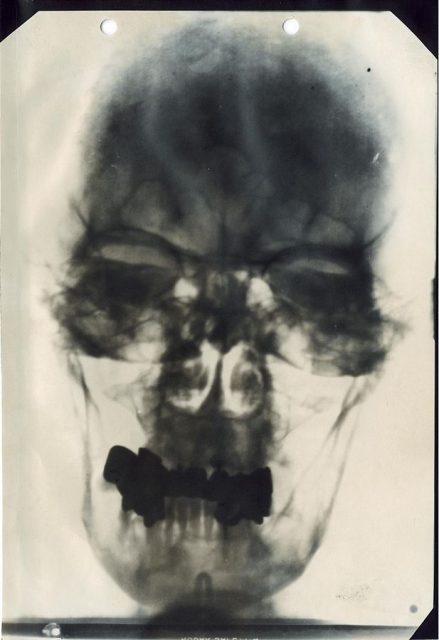

Yelena decided that the place to start was to find Hitler’s dentist. This was a mind-boggling task in the chaos that was Berlin at that time. She began by searching the cabinets of the Chancellery and found a file that contained x-rays of Hitler’s teeth and his dental records. She then set off with her driver and two other officers into the smoke and wreckage of the ruined city. Working their way around barricades, burned tanks, and other wreckage they eventually arrived at the hospital to try and locate the dentist himself.

No-one at the hospital knew who Hitler’s dentist was, but they directed Yelena and her entourage to the Charite Clinic, suggesting that Professor Carl von Eicken, who headed up the clinic, may well know. Back in their car, they headed for the Clinic and found a grim building painted with camouflage stripes for protection against air strikes. The department they were looking for was in the basement, and the building proved to be every bit as grim inside as out. Nurses, utterly exhausted, cared for the patients, with more and more wounded arriving all the time. Finding Professor von Eicken in the Ear, Nose and Throat Department, they asked him about the missing dentist and though he personally didn’t know, he took them to the dentistry section where they discovered that the dentist they sought was a Dr. Hugo Blaschke. The Russian team was directed to Dr. Blaschke’s surgery, which was located on Kurfurstendamm, one of Berlin’s most fashionable streets.

Arriving at the surgery, the Russian team was told that the dentist had fled to Bavaria. Not put off by this information, the Russians began searching the dentist’s rooms. In questioning the staff, they found that Dr. Blaschke may be in contact with one of his staff, a woman by the name of Kathe Heusermann. She was summoned to the surgery and soon a very pretty blond lady appeared. When she was told that the Russian team wanted to see her, she burst into tears fearing that she was to be raped again. Sadly, this was a fate that many German women suffered as the Allied forces rolled over Germany.

She was reassured that this group of Russians meant her no harm and Yelena spoke gently to her, asking if she knew where Hitler’s dental records were. Ms. Heusermann took out a box of cards, and as she flipped through them, the Russian saw cards for many members of the German High Command, along with their wives and children. Eventually, they found Hitler’s card, but the x-rays could not be found. Ms. Heusermann suggested that the only other place to search was the dentist’s surgery within the Reich Chancellery.

The Russian team was not sure that they would be able to find anything as the Chancellery was mostly a smoking ruin but they went with Ms. Heusermann and entered under the Nazi emblem of an eagle with the swastika in its talons. She led them to a dark room where the team could see a dentist’s chair and a small desk. Looking through the cabinets, the Russians hit pay-dirt and found the x-rays and dental records that they were looking for.

The next day, the Russian team sat with Ms. Heusermann and asked her to carefully describe Hitler’s teeth as she remembered them. With Yelena translating, they slowly documented the dental assistant’s memories with Yelena making careful notes of the specific names of the teeth, not simply their number in the mouth. She was careful to ensure there could be no ambiguity as to what the dental assistant said.

One sentence that Ms. Heusermann used provided the proof they were looking for. Ms. Heusermann stated that a gold bridge connected the 1st and 2nd and 3rd left teeth. She carefully described the crowns and roots of the teeth. The Russian team compared her description with the x-rays they had found and saw that her description matched the x-rays completely. Now for the final proof; did they match the contents of the dark red box? Comparing the description to the contents of the box, they found a 100% match. Here was the incontrovertible proof that the teeth belonged to Hitler. Yelena took them out of the box and passed them to Ms. Heusermann who positively identified them as Hitler’s teeth.

Yelena was convinced that the all rumors of Hitler escaping Berlin would now be laid to rest, but she was wrong. Stalin insisted that the proof was kept hidden as he detested the idea of talking with the Germans, and he believed that the knowledge of Hitler’s death or survival would be of tactical use in the discussions that would follow the peace negotiations. When, at the Potsdam Conference, he was asked if the Russians had any proof of Hitler’s demise he simply denied any knowledge.

Unfortunately, this meant that Kathe Heusermann became a possible embarrassment to Stalin, so she was imprisoned for ten years and labeled a dangerous criminal. She came close to starving to death until a fellow prisoner shared their food with her.

No-one knew what had happened to Hitler’s teeth after May 1945 until 2000, when the Russian authorities placed them on display as part of an exhibition to celebrate the 55th Anniversary of the end of WWII.

Yelena had returned to Moscow when her work in Berlin finished, but she only managed to find out what had happened to Heusermann in 1996. Yelena died in April 2017.

Without the work done by these two ladies, the world may well never have known for sure what happened to Hitler.