German Chancellor Angela Merkel and French President Francois Hollande met in Verdun, the site of a 300-day WWI battle that failed to produce a victor.

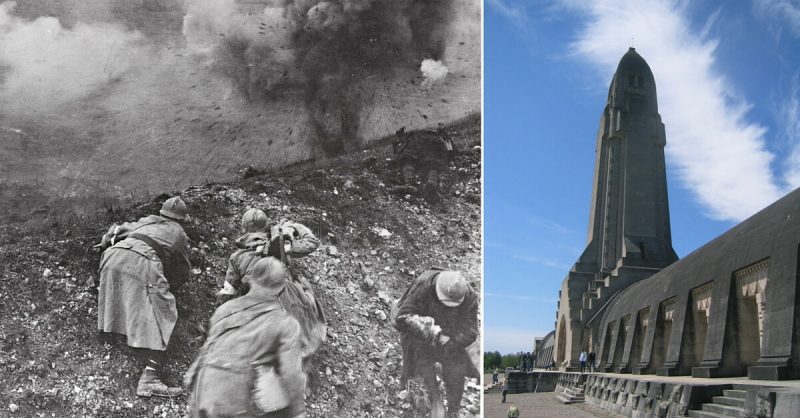

“Operation Judgment” began on the morning of February 21, 1916 with a nine-hour long barrage from hundreds of German artillery. Nothing like it had ever been seen before; the sound of the cannons could be heard 120 miles away. Ernst Jünger, the German author, called it a “storm of steel.” World War I had started a year and a half earlier, but Verdun became its enduring symbol.

During the battle, hundreds of thousands of French and German soldiers lost their lives.

The hills of Verdun along the Meuse River were not just a strategic military location for the French; they were a symbol of the long-running conflict between France and Germany. It was there that the Carolingian Empire was divided into three kingdoms. It was there that eastern and western France would evolve at the end of the medieval period. The French were not going to allow a place of such historical significance to fall into the hands of the Germans without a fight.

Verdun was not a good place for the Germans to strategically begin an invasion into France. Supreme Commander Erich von Falkenhayn was not just looking for a breakthrough, but for the chance to bleed the French dry.

Philippe Pétain was the commander in charge of defending Verdun. More than 70% of all French soldiers were ordered to fight at least once in the trenches of Verdun for eight to 10 days. Someone from almost every family in France participated in the battle, with the greatest numbers between February and June of 1916.

Starting in July 1916, von Falkenhayn put the German military in the area on a “strict defensive” as German troops were needed elsewhere, particularly on the Somme front. By October, the French were advancing. By December, they had retaken most of the lost territory. However, it is less accurate to say that the French “won” than to say that they outlasted the Germans in a great human catastrophe.

According the military calculations, around one million steel projectiles weighing 1.35 tons landed in an area of less than 12 square miles. The noise deafened many in the area, leaving some soldiers with profound trauma in later life.

“Unlike the ‘war of movement’ on the Marne,” the military historian German Werthe once wrote, “the battle in the Meuse region was characterized by dullness and monotony, which made it a symbol of the lethal banality of the four years of trench warfare.”

In Douaumont, the ossuary is a touching memorial to the men who died in that battle. Inside the main tower lie the remains of 130,000 French and German soldiers, all unknown. Even to this day, random bones from gardens, fields, and forests are brought to the ossuary.