For the United States during the Cold War, no project was too crazy or too expensive. One of these, known as Project Azorian, cost the equivalent of $4 billion in today’s money. This funded a major recovery effort on the seafloor. The project took place in the 1970s and was an unprecedented undertaking at the time. It was one of the most complex and extensive projects of the Cold War.

What was it for? Well, to find out more about the Soviets, obviously.

In 1968 the Soviet submarine K-129 became the subject of intense interest from American intelligence services.

At the time K-129 was a rather dated design, as it was launched in the late 1950s and many technological advancements had been made since then. She was a Golf II-class submarine (NATO’s reporting name) that was 100 meters (330 ft) long and weighed 3,000 tons. In 1964 the submarine underwent extensive modernization upgrades, receiving the Soviet Union’s latest electronic systems.

But what made her really special was her armament of the newest submarine-launched nuclear ballistic missile, the R-21. The R-21 was the first Soviet missile that could be launched underwater, and for the 1960s, was extremely advanced technology.

K-129 is lost

A Project 629A (NATO reporting name Golf-II class) diesel-electric Soviet ballistic missile submarine K-129, hull number 722. (Photo Credit: CIA / Public Domain)

In 1968 K-129 set out on a patrol in the Pacific Ocean that would last from February to May 5, but by March she had failed to make her scheduled radio check-ins to her headquarters. After repeated attempts to contact her, the Soviet Navy ordered that she break radio silence to inform them of her status. By the third week of March, K-129 had still not made contact, so the Soviets declared her missing and launched an enormous search and rescue effort conducted by 40 vessels and 53 aircraft over the course of two months.

Without any sign of K-129, the search was called off.

The Americans are listening

Being the 1960s, the US was naturally curious as to what could have caused such a stir in the Pacific. They knew for the Soviets to make such an effort, they had lost something important.

The US was presented with an opportunity to peer behind the curtain of the Soviet Union, so they began investigating themselves. The US simply referred to their Sound Surveillance System (SOSUS) that was set up throughout the 1950s and 60s to listen to Soviet submarine activity. They quickly discovered that SOSUS had picked up an underwater explosion near the Soviet search area.

They triangulated the position of the sound to a five-mile area and dispatched the submarine USS Halibut to visit this location. Before October 1968 the US found the wreckage, situated 4,900 meters (16,000 ft) below the surface. Halibut spent three weeks studying the wreck and took 20,000 photos. The US found that K-129 remained mostly intact, and still contained R-21 missiles.

But finding the wreckage was not enough for the US. They wanted to raise it.

Raising K-129

Nothing like this had been done before, especially with the depths and weights involved with the K-129 wreckage. To keep such an enormous project a secret, the US handed it over to the CIA.

To raise the submarine, the CIA discussed using rockets or inflatable balloons, but both of these were simply too unpractical. They eventually settled on using a huge claw to pick up K-129.

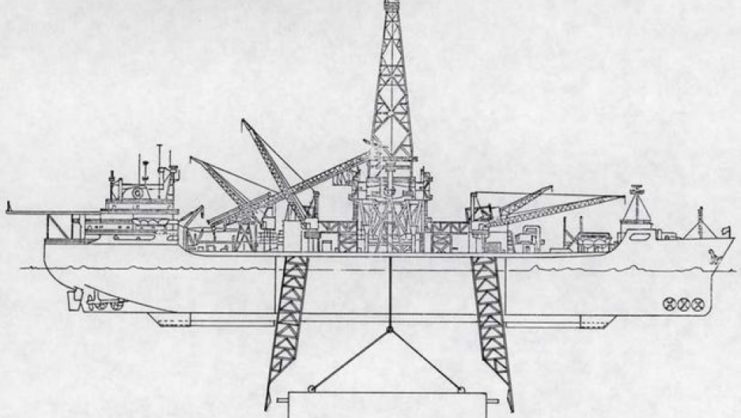

Lockheed was tasked with designing the claw, which would be lowered from a task-specific vessel on the surface. Global Marine, a world-leading deep-sea mining company, was to construct the ship.

As a result, Global Marine produced the 190-meter (618 ft) long Glomar Explorer. Its hold featured a large moon pool for the K-129 to be lifted in through.

However, the CIA faced another problem: how do they convince the world that a major operation being conducted in the Pacific was not a secret government mission?

They solved this problem with eccentric billionaire business magnate Howard Hughes. Hughes was extremely wealthy, was no stranger to large projects, had worked with the government before, and no one would be surprised to see him funding an ocean-floor-based mission. He was the perfect man for the job.

Glomar Explorer arrived above K-129 in 1974, six years after the submarine was lost. During the preparation for the task, the group was buzzed by Soviet ships, but fortunately, the cover story had worked.

The claw was able to grab onto the submarine, but during its ascent to the surface the equipment partially failed, causing over half of K-129 to drop back down into the abyss. Despite this, the mission successfully collected a large portion of the submarine. The exact contents of the recovery are still classified to this day, although it is rumored to have contained important documents and nuclear weapons.

The US planned another mission to retrieve the rest of the submarine, but this was aborted when the entire operation was exposed by a reporter.

Are you a fan of all things ships and submarines? If so, subscribe to our Daily Warships newsletter!

The US did find six bodies and the remains of even more in the wreckage. These sailors were given a proper sea burial, which the Americans filmed and sent to the Russians in 1992.