At exactly 2:25 PM, Confederate Colonel Edward Porter Alexander scribbled this note and rushed it off to General George Pickett: ”If you are coming at all you must come at once, or I cannot give you proper support, but the enemy’s fire has not slackened at all. At least 18 guns are still firing from the cemetery itself.”

But those 18 Federal guns began to fall silent. So, Alexander watched carefully, waiting to see if the Confederate artillery barrage had done its job.

It was July 3, 1863, moments prior to what remains the most well-known, controversial, and roundly debated infantry assault in American military history, forever known as Pickett’s Charge. Smoke was still swirling from the greatest cannonade the North American Continent had ever witnessed as Alexander peered through his glasses, trying to fathom if the Rebel bombardment had created the necessary conditions for their infantry to advance.

He watched closely as Federal batteries limbered-up and departed the critical area (which he incorrectly thought was a cemetery), while none replaced them. After five minutes of meticulous observation, he scribbled another note, sending it off at 2:35: “For God’s sake come quick. The 18 guns are gone. Come quick or I can’t support you.”

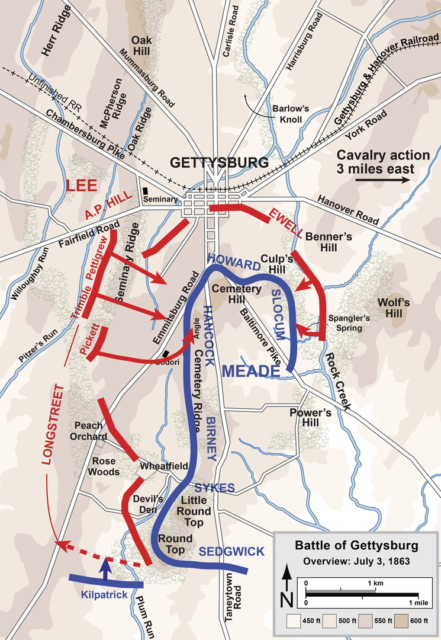

Two days earlier advanced elements of both armies had collided west of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania in a meeting engagement neither side wanted nor sought. Nevertheless, troops were fed into the maelstrom as they arrived, and by days end the Federals were beaten back, only to reform on Cemetery Ridge, south and east of town. The Confederate Army then took position on Seminary Ridge, facing the Federals about a mile west.

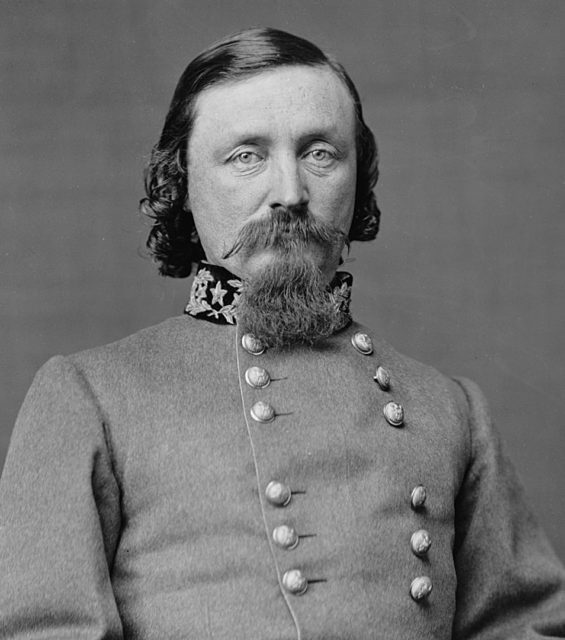

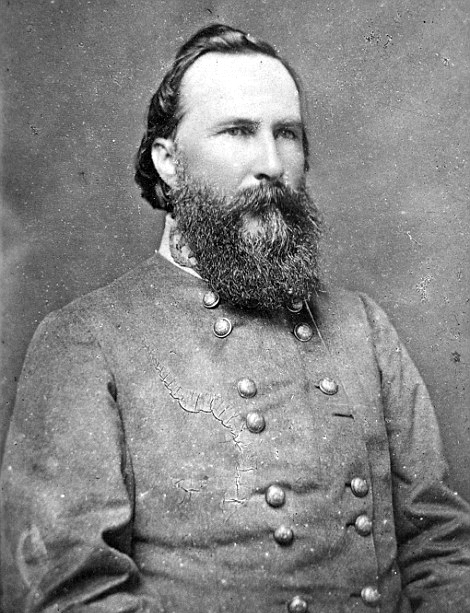

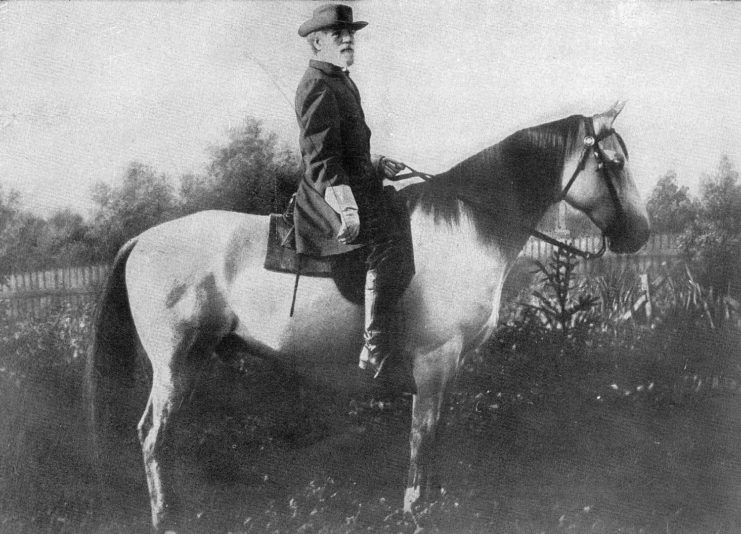

The following day, July 2, General Robert E. Lee, the Rebel commander, tried to sweep the Federals from their position with a massive assault along the Union left flank, which ultimately fell short, setting up a do-or-die Confederate attempt on day 3. Receiving Alexander’s dispatch, Pickett raced to General James Longstreet, who General Lee had placed in overall command of the day 3 attack. Pickett requested permission to advance. Believing the assault would fail, Longstreet said nothing. He apparently could not bring himself to give the order he fancied

ruinous, not only for the battle, but perhaps even for the Confederate cause. Pickett waited a moment or two, then said: “I am going to move forward, Sir.” Once again, Longstreet did not respond.

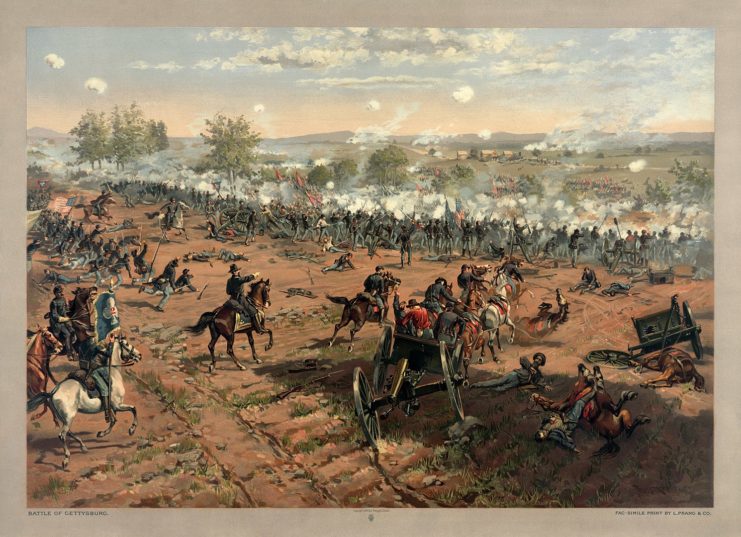

It was a steaming-hot Pennsylvania afternoon. Winds whipped the trees as the grey-clad and butternut divisions assembled, then moved from the cover of trees out into the open. From across the valley almost a mile away the Federal divisions watched in sudden awe, and for a moment time seemed to hang in suspension, as if marking the occasion.

As novelist William Faulkner later wrote in Intruder in the Dust: “For every Southern boy fourteen years old, not once but whenever he wants it, there is the instant when it’s still not yet two o’clock on that July afternoon in 1863, the brigades are in position behind the rail fence, the guns are laid ready in the woods and the furled flags are already loosened.”

Longstreet rode out to where Alexander was observing the Federal position, and when Alexander notified him the ammunition was critically low, he insisted that Pickett be stopped, and Alexander

immediately replenish his supply. But that would take an hour or more, he was told, and the Federals would be far better off in an hour than they were at present. “Our only chance,” said Alexander, “is to follow it up now – to strike while the iron is hot.”

Longstreet, despondent, replied haltingly. “I don’t want to make this attack. – I believe it will fail – I do not see how it can succeed – I would not make it even now, but that Gen. Lee has ordered & expects it.”

Alexander said nothing. A long, gloomy silence hung between the two officers for perhaps twenty minutes as Pickett, and the other Confederate commanders, readied the assault. Alexander recalls the

moment: “I do not recall looking at my watch again that day.” Then he glanced back and “I saw Pickett’s line approaching at a good fast gait.” Victory in battle – and perhaps the war – now hung in the balance.

Hours before, in the stillness before dawn, Robert E. Lee had risen, breakfasted, then called for his horse. Riding up the western slope of Seminary Ridge, he sought Longstreet, such that the two might confer on the strike Lee now planned to make. Earlier plans for a morning attack had been scrapped.

Now Lee wanted Longstreet – with the addition of Pickett’s division, recently arrived – to launch his entire corps at the Federal line on Cemetery Hill, striking just north of Little Round Top, on the far left of the Federal position.

Longstreet listened intently, we are told, with a growing sense of demoralization. For what Lee now proposed was essentially what Longstreet had attempted the day before, yet a strike that had been repulsed at every point. To try it again after having sustained heavy losses – even with the addition of Pickett – seemed foolish, if not desperate.

Longstreet suggested, rather, a turning movement around the Federal left, which Lee rejected out of hand. Lee pointed forcefully toward the Federal line. “The enemy is there,” he exclaimed, “and I am going to strike him.”

The two conferred for some few minutes more, Longstreet pointing out that any such strike would expose the right flank of the attacking party, and that his division had been seriously diminished in the previous day’s fighting. Lee concurred, agreeing to fix the point of attack farther north, while supplanting two of Longstreet’s brigades with two from A. P. Hill’s division. That would bring the strength of the proposed assault up to 15,000, sufficiently powerful, it was thought, to break the center of the Federal line.

But Longstreet believed Lee’s decision to be ruinous and, after careful consideration, spoke his mind. “General,” he said, choosing his words with great care, “I have been a soldier all my life. I have been with soldiers engaged in fights by couples, by squads, companies, regiments, divisions, and armies, and should know as well as anyone what soldiers can do. It is my opinion,” he continued, pointing toward Cemetery Ridge, “that no 15,000 men ever arrayed for battle can take that position.”

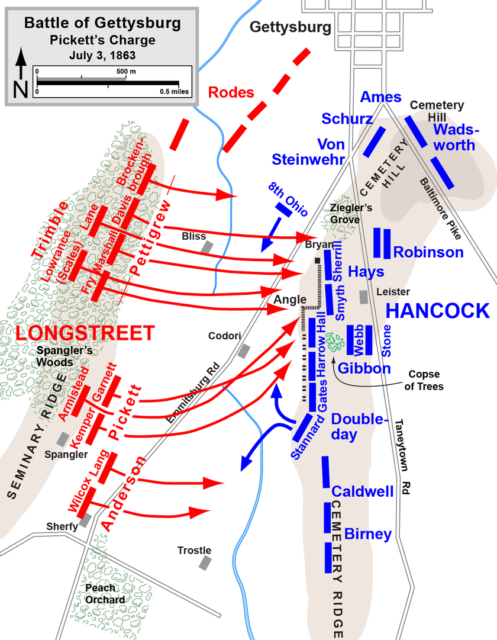

Lee’s mind was made-up, however. Pickett was summoned, but Lee did agree to augment the attacking force with four of Heth’s brigades, to be commanded by Johnston Pettigrew, since Heth was down. The divisions were to be aligned with Pettigrew on the left, Pickett on the right, with Pettigrew’s front line supported by the brigades of Lane and Lowrance. Picket’s front was to be supported by Armistead, with the additional brigades of Wilcox and Lang, if necessary.

The objective was a small clump of trees near what Alexander thought to be the graveyard on Cemetery Ridge, essentially the center of the Union line. To accomplish this, the assaulting troops would have to cross over almost 4/5 mile of open, undulating farmland. Initially, there would be a gap between the two attacking divisions, then, as the assault commenced, the left flank of Pickett’s troops would join the right flank of Pettigrew’s, ultimately forming a unified front at the point of attack.

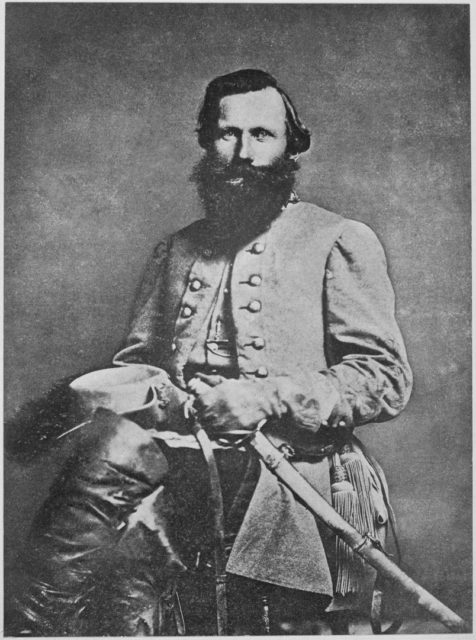

Augmenting the infantry assault, Lee ordered the commander of his cavalry, the flamboyant J.E.B. Stuart, to circle around the Federal right flank with some 4,500 cavalrymen and strike their rear in cooperation with the Pickett’s assault. His mission was to create confusion among the fleeing Federal fugitives, and hopefully connect with either Pickett or Pettigrew’s divisions, thus slicing the Federal Army in two.

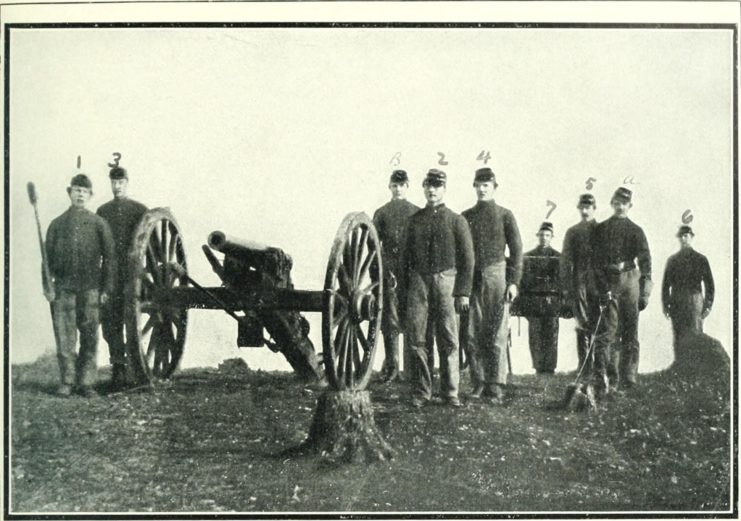

The infantry attack was to be proceeded by a short but altogether shocking cannonade meant to silence the Yankee artillery, while scattering and bewildering their infantry. To accomplish this, 80 guns from Longstreet’s Corps were deployed along a one-mile arch fronting Seminary Ridge, another 63 guns from Hill’s Corp adding their thunder farther north along the Ridge. In all, those 140 guns represented the greatest concentration of artillery ever aligned for battle in North America.

Colonel Alexander, commanding Longstreet’s artillery, recalled the situation: “My orders were as follows. First, to give the enemy the most effective cannonade possible. It was not meant simply to make a noise, but to try & cripple him—to tear him limbless, as it were, if possible…When the artillery had accomplished that, the infantry column of attack was to charge. And then, further, I was to ‘advance such artillery as you can use in aiding the attack’”

Across the valley on Cemetery Ridge, the Federals had also unlimbered a daunting array of batteries along the entire length of their position, from Culp’s Hill to Little Roundtop. “The Federal guns in position on their lines at the commencement of the cannonade were 166,” Alexander tells us, “and during it 10 batteries were brought up from their reserves, raising the number engaged to 220.”

For hours the two lines eyed one another silently across the valley, but seven minutes after 1 o’clock that silence was suddenly interrupted by two shots from the Washington Artillery, positioned near the center of the Confederate line. It was the signal for the cannonade to commence. “As suddenly as an organ strikes up in church,” Alexander recalled, “the grand roar followed from all of the guns.”

The Federal artillery responded, and the small valley was suddenly alive with smoke, death, and shrieking shells. The ground reverberated, as if continually rattled by a string of small, but unending earthquakes. The combination of artillery fire was so loud that 90 miles distant in Philadelphia people gazed into a clear sky, expecting a thunderstorm, and the roar was reportedly heard 150 miles away.

Colonel Frank Haskell, a Yankee staff officer situated near that clump of trees the Confederates had selected as their objective, later wrote one of the most compelling and literary accounts of the moment.

“We watched the shells bursting in the air, as they came hissing in all directions. Their flash was a bright gleam of lightening radiating from a point, giving place in the thousandth part of a second to a small, white puffy cloud, like a fleece of the lightest, whitest wool…The shell would seem to stop, and hang suspended in the air an instant, and then vanish in fire and smoke and noise.”

A civilian in town, crouching in her basement, thought the thunder sounded “as if the heavens and earth were crashing together.” So intense was the concussive effect, many soldiers reported blood dribbling from their ears and noses.

Soon the valley became engulfed in smoke, such that all the gunners could manage was to fire at the red muzzle bursts a mile distant, hoping for the best. Most of the Confederate shots flew long, however, causing pandemonium behind the Yankee lines, but failing to dislodge much of their artillery or infantry.

Then the Federal guns began to fall silent, but this was not due to the effectiveness of Rebel artillerists, but rather orders from General Henry Hunt, chief of Federal artillery. Wanting to conserve ammunition, Hunt had given the order, hoping it might induce the Rebels to initiate their infantry assault which, by then, everyone knew was coming. The ploy worked, and at 2:35 Alexander sent the fateful note to Pickett, urging him forward.

The Confederate infantry – which had waited out of sight in the woods along Seminary Ridge during the cannonade – now emerged and formed once again in the bright sun and open fields south of Gettysburg. They formed along an extended front that, according to the American Battlefield Trust, stretched across the undulating farm fields for over a mile. For the Federals on the ridge opposite, the sight was breathtaking.

Colonel Haskell: “None on that crest now need be told that the enemy is advancing. Every eye could see his legions, an overwhelming resistless tide of an ocean of armed men sweeping upon us! Regiment after regiment, and brigade after brigade, move from the woods and rapidly take their places in the lines forming for the assault.”

The actual number of men arrayed for battle that afternoon has been hotly debated since 1863, but due to faulty Confederate casualty counts for days 1 & 2, will probably never be known with any precision.

Earlier assessments had gauged the combined strength of the attack at roughly 12,500, less than what Lee had counted on.

But more current analysis suggests the strength of Pickett’s (5,830) and Pettigrew’s (6,761) divisions actually totaled closer to 12,591. Adding the combined weight of Wilcox and Lang’s brigades at 1,480, the number of infantrymen arrayed for assault that hot afternoon now appears to be about 14,071, but still less than what Lee had calculated necessary to break the Federal line. (Trudeau, 2002)

When at last the lines were set and properly dressed, the order to advance was given, and the massive assault lurched forward. Again, Haskell, recalling every detail, breathes life into the scene: “The red flags wave, their horsemen gallop up and down; the arms of eighteen thousand men, barrel and bayonet, gleam in the sun, a sloping forest of flashing steel. Right on they move, as with one soul, in perfect order, without impediment or ditch, or wall or stream, over ridge and slope, through orchard and meadow, and cornfield, magnificent, grim, irresistible.”

Soon the Federal artillery opened, with deadly effect. Marching at “common time” it would require almost twenty minutes for the advance to traverse the open valley, twenty minutes in which they would be mauled by long and short range shells, before marching directly into the gun sites of the Federal infantrymen, ready, and waiting.

Wyman White, nearby with the U S Sharpshooters, recalls the Confederate charge: “They came at a quick step until about half the distance had been crossed, then they deployed into several lines and charged at a double quick until our fire seemed to partly paralyze their ranks, so their advance was hardly perceptible in the smoke.”

Firing from enfilading angles, the Union artillery could hardly miss, and the results were gruesome. Atop Little Roundtop, Lt. Rittenhouse observed the effect his battery of six rifled guns had on the Rebels. “I watched Pickett’s men advance, and opened on them with an oblique fire, and ended with terrible enfilading fire,” he later wrote. “Many times a single percussion shell would cut out several files, and then explode in their ranks; several times almost a company would disappear, as the shell would rip from the right to the left among them.”

Despite enormous losses, the assault pushed on, men stepping forward to take the places of the fallen. The front line finally reached the fencing that ran the length of the Emmitsburg Pike, which fronted Cemetery Ridge at a distance of a few hundred yards. Here the Confederates began to clamber over the fence and at once became targets for Federal infantry.

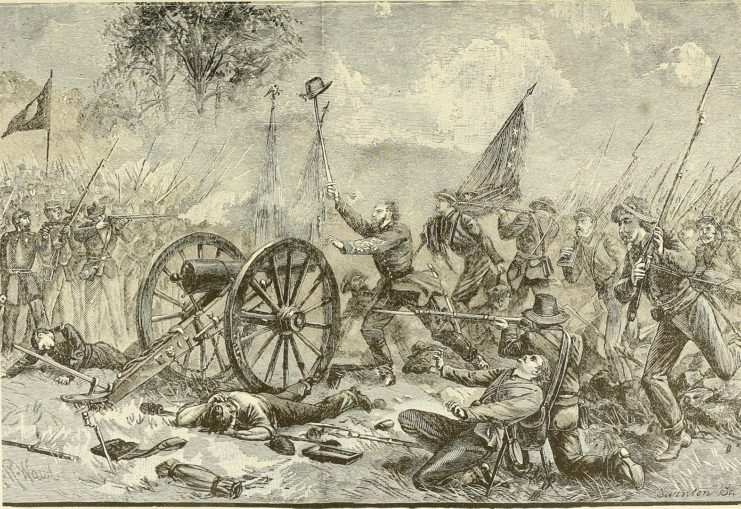

Rebels were cut down by the dozens as the Yankee fire intensified. Red battle flags tumbled, men staggered to their knees or were blown backward by a torrent of small arms and artillery fire. Nevertheless, somehow a mass of grey soldiers made it across the road and started straight toward the clump of trees that was their objective.

Meanwhile, on both the right and left, Yankee infantry formed along the flanks of the Confederate assault and began firing into the Rebels at close range. Watching from Seminary Ridge, one Confederate recalled the sight as “a vast bank of thick battle smoke, with thousands of shells exploding above the surface of a white, smoking sea.” What remained of the great assault – mauled, battered, and bloodied – jumbled together like a great angry fist, then surged forward toward the trees and the low stone wall that fronted them.

Lewis Armistead, leading Pickett’s supporting brigade, led the way, his hat placed on the tip of his sword. “Come on, boys!” he cried. “Give them the cold steel! Follow me!” Armistead led a few hundred men over the wall and was gunned down almost immediately, falling only feet from where he had crossed over.

Some of those hundreds managed to follow him over, however, and on the Federal side the two forces collided in a wild brawl of shots and shouts and sabers and fists. General Hunt was waiting near the trees, sitting his horse, screaming, “See ‘em! See ‘em!” as he emptied his revolver into the surging grey mass.

Men were screaming, hollering, fighting as guns fired, smoke swirled, and men toppled to the earth. The roar of combat was at this point so guttural, so primitive that one man recalled it as “strange and terrible, a sound that came from thousands of human throats, yet was not a commingling of shouts and yells but rather like a vast mournful roar.”

Importantly, as historian Noah Trudeau points-out – and suggestive of the truly do-or-die nature of the assault in Lee’s mind – General Lee had put an additional 11 brigades totaling some 11,000 men on notice to support the assault, but for reasons unknown, this massive force was never utilized.

Hence, as Armistead led his small band over the stone wall, there would be no Confederate reinforcements to support them. Perhaps Longstreet, believing the assault doomed from the start, refused to sacrifice more men in what he fancied a lost cause, thus only speculation remains as to what may have happened had those additional brigades been vigorously employed.

Federal reinforcements raced to the scene, but for the Confederates there were none, and soon the few hundred were shot or clubbed or beaten otherwise into submission. The great assault had not so much been repulsed as it had simply dissolved under a coordinated avalanche of fire.

To make matters worse, the Brigades of Wilcox and Lang were advanced after the assault had reached its climax. As a result, they accomplished nothing but draw fire from a whole range of Federal artillery on Cemetery Ridge, losing countless more men in an effort that did not accomplish, and could not have accomplished, a thing.

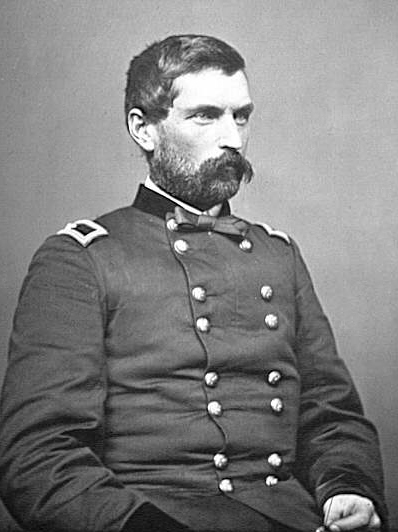

Meanwhile, 3 miles behind Cemetery Hill, Stuart’s attempt at striking the Union rear was foiled when a freshly minted, twenty-three-year old brigadier general named George Custer Armstrong spotted Stuart’s approach. Screaming “Come on, you Wolverines!” Custer led his entire Michigan cavalry brigade in a wild charge against the grey riders. That charge in turn inaugurated a raging cavalry struggle that spilled back and forth across the fields east of Gettysburg, until Stewart was forced to withdraw.

Back across the valley the remnants of the great assault ran or crawled or limped their way back toward Seminary Ridge, as the Yankees stood by their stone wall and screamed “Fredericksburg!

Fredericksburg! Fredericksburg! payback for that horrible day in 1862 at Marye’s Heights when they themselves had been savaged, trying to repeatedly attack troops positioned behind a stone wall.

As the broken men of Pickett’s and Pettigrew’s divisions stumbled back up the slope of Seminary Ridge, General Lee was there to meet them, offering fatherly reassurance. “All this will come right in the end,” he said, riding amongst them. “The blame is mine,” he repeated, absolving his men of any failure. “It’s all my fault.”

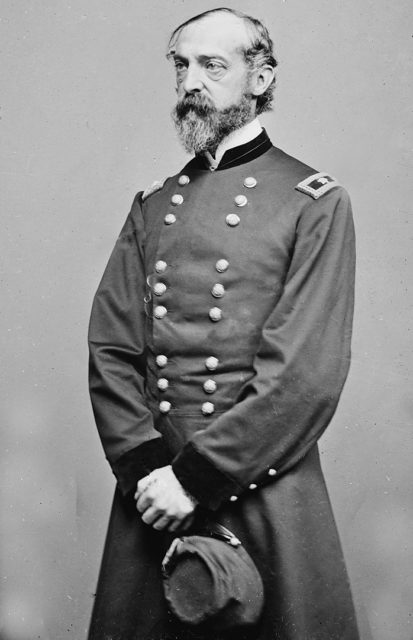

Expecting a Union counterstroke, the Confederates tried to mount a feeble line of defense, but that counterstroke never fell. Stunned by the day’s success, General George Meade, the Federal commander, was content to leave well enough alone, his casualties for the attack estimated at 2001. The sun eventually set on a mangled landscape of human carnage, followed in turn by a great thunderstorm, as if God intended to wash the horrific scene from memory.

Confederate losses were staggering. Of the roughly 14,071 men who comprised Pickett and Pettigrew’s main attack (including the brigades of Wilcox and Lang) 5,236 went down, killed, wounded, or missing.

Pickett’s Division alone suffered a 45% casualty rate. Every officer above the rank of captain in Pickett’s Division, save one, was either killed or wounded. Pettigrew’s Division was likewise decimated. “In Fry’s brigade two field officers escaped, in Marshall’s only one, and in Davis’s all were killed or wounded.”

Total casualties represented 37% of the attacking force.

General Lee had marched into Pennsylvania confident of a victory that might end the war in the South’s favor. His army would leave severely crippled, never again able to mount a serious offensive. After Gettysburg Lee was reduced to a war on the defensive, a war of attrition, of numbers, and a war in the long run, the South could not win. Lieutenant John T. Williams, of the 11 th Virginia, later summed up the Confederacy’s disaster at Gettysburg in a letter home. “We gained nothing but glory and lost our bravest men.”

by Jim Stempel

Jim Stempel is a speaker and author of nine books and numerous articles on American history, spirituality, and warfare. His newest book regarding the American Revolution – Valley Forge to Monmouth: Six Transformative Months of the American Revolution – will be released in November. For a full preview, pricing, and pre-publication reviews, visit Amazon here (https://amzn.to/34J4fZN) Or, visit his website (https://bit.ly/2EAWNVT) for all his books, reviews, articles, biography, and interviews.