A new online exhibition of photographs, music, recipes and information gives the viewer a taste of the contribution made by Philadelphia to America’s effort during World War I. This online exhibition follows on the success of the Together We Win: The Philadelphia Homefront during the First World War exhibition that ran between the 11th November 2016 until the 21st April 2017. The exhibition was put on by the Library Company of Philadelphia.

This interesting and innovative on-line exhibition has sections that cover all that was seen during the live exhibition. There are sections showing photographs of life in Philadelphia during this period from both military and civilian viewpoints and recordings of popular wartime music. There are posters that the authorities used to urge Americans to conserve food and buy war bonds to raise money for the war effort and a few recipes for dishes popular during that era.

Some of the fascinating aspects that you can enjoy are:

National League for Woman’s Service

Based at “Little Wakefield” in Germantown, this League taught women how to contribute to the war. Their slogan was “if you cannot be a fighting soldier, be a farming soldieress” and their classes in home economics and basic food production were immensely popular. The ladies were taught basic farming, and they grew a range of fruits and vegetables such as peas, corn, peaches, raspberries, and cabbages as well as cultivated bees. This building is now St. Mutien’s Christian Brothers’ residence on the La Salle University campus.

Food Conservation during WWI

Sugar was hugely important in the manufacturing industry within Philadelphia with 130 chocolate, and candy manufacturing concerns within the city and several large sugar refineries were based on the Delaware River. Some amazing statistics from the time showed that Americans ate, on average, 85 lbs sugar per person per year, when compared to the English who ate 40 lbs sugar and the Germans who ate 20 lbs. This poster from the war years shows how many ships were needed to import all this sugar and perhaps there are still lessons for us to learn today!

Industry in Philadelphia during the war

Philadelphia boasted the world’s largest shipyard, Hog Island, built during the war years. A local newspaper, the Philadelphia Inquirer, covered the launching of the first ship from the shipyard. They estimated that around 100,000 people braved the summer heat to see the Quistconck take to the water for the first time.

The Women’s Permanent Emergency Association of Germantown

This association was founded in 1889 to provide emergency assistance to the victims of the Johnstown flood, but with the outbreak of war in 1914, they began to support the Belgian refugees. When America entered the war, their relief efforts stepped up a gear, and by the end of the war, they had sent more than 7,500 articles of clothing, 65,000 items of hospital supplies and more than 5,000 knitted garments.

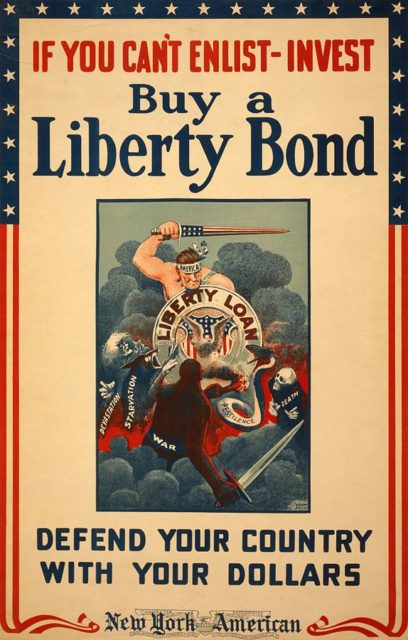

War Bonds

The cost of the war was bound to strain the government coffers, and huge drives were held to raise money by persuading the general public to buy War Bonds.

Not only were posters employed to great effect but also public parades were used to exhort the public to assist with financing the war. These parades were called Liberty Rallies, and their aim was to raise money. In this photograph, one of the big sugar refineries in Philadelphia, McCahan’s Sugar Refining Company, dressed a truck with young ladies wearing the national dress of America’s allies with a large sign proclaiming that 600 of their employees had bought war bonds.

Peace is proclaimed

A copy of the Statue of Liberty was erected outside the Philadelphia City Hall, and it became a rallying point for many rallies. Later this statue was replaced by a copy of the winged Victory and when the news came through that peace had been declared the city erupted spontaneously. Thousands of people jammed the city center to celebrate the end of the war and one resident; Morris G. Condon III wrote: “A solid seething mass of humanity stacked shoulder to shoulder as far as you could see was jammed in the streets. I can still hear my father swearing, pulling my mother through the crowds, and she, near tears, pulling me. It seemed everyone in the city was jammed into the City Hall area in all directions.”

The war had come to an end, and the residents of Philadelphia celebrated with everyone else, but grim reminders of the price paid by so many would soon become evident. Men brutalized by the war and many sporting grievous wounds soon arrived back in the city, and the grim reality of war was brought home to all residents. Yes, they had done their part and risen to the occasion, but none of them appreciated the cost of this war on their sons, husbands, and fathers until these men returned to them, HuffPost reported.

Slowly life returned to ‘normal’ as the industry once again started and residents no longer had to go without in support of the war effort. New crises would arrive but everyone was touched by the war and World War I would not be forgotten so quickly.