Prominent French journalist Anne Sinclair is the daughter of legendary Parisian art dealer Paul Rosenberg. She is now 68.

On February 23, she opened an exhibition at Musée Maillol of 66 paintings that once passed through her grandfather’s gallery: they represent modernist masterpieces in 20th-century art: cubism, expressionism, and Fauvism. They are also a witness to the brutality and darkness of the Holocaust.

The exhibit entitled ‘21 rue La Boétie,’ after the address of Rosenberg’s original Paris gallery and her own memoir, is an earlier version, which opened in Liège last fall.

Rosenberg was an early proponent of Pablo Picasso, George Braque, and Henri Matisse. A number of his most valuable pieces, including a 1918 Picasso portrait of the dealer’s wife and daughter, were stolen by Hermann Goering, the high-ranking Nazi official, and expert on stolen art pieces.

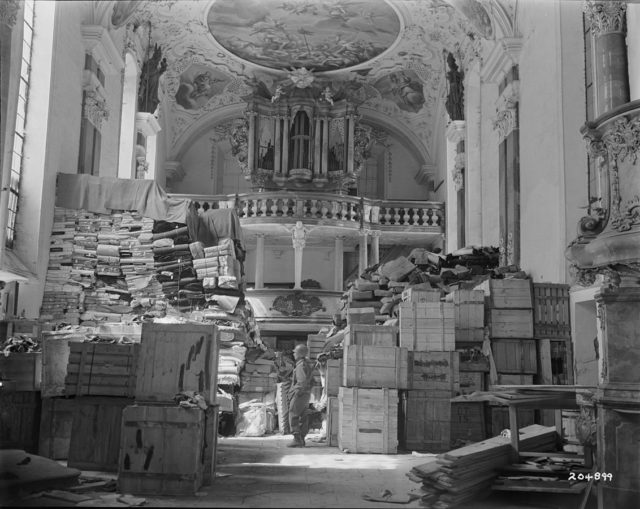

After Germany invaded France in 1940, the Nazis took hundreds of thousands of works of art from Jewish dealers and collectors. The French government estimates approximately 100,000, but specialists say the number is at least triple that. In cruel sarcasm, the Nazis changed the mansion into what they termed the Institute for the Study of the Jewish Question throughout the war.

Since her grandfather’s passing in 1959, Sinclair and her family have endeavored to recover as many missing works from the Rosenberg collection as possible, often being involved in prolonged legal battles.

For Paris-based art historian Emmanuelle Polack, who steered most of the research to recover two Matisse canvasses that were returned to Sinclair and her family, the restitution project is both collective and personal.

“When you return a painting, you give back an identity, a memory, a family, but also a culture,” Sinclair said.

Close to 100 years after the end of the Second World War, the story of the Nazi onslaught on European art, owned by Jews or otherwise, is well documented. Following the war, the Nuremberg trials listed looting as a war crime. Following decades of delays, a number of high-profile compensation cases have been victorious.

In 2006, the Austrian government was forced to return a famous Gustav Klimt portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer, the wife of a Jewish industrialist who later passed away in exile after Nazi persecution, to her niece.

In most cases, restitution is not the rule but the exception. The burden of proof lies with the plaintiff. Public institutions usually resist returning works of art held in their possession for decades.

Matters are further complicated when a particular artwork might have been stolen by the Nazis from its original Jewish owners but then legally obtained by an unsuspecting purchaser after the war. In addition, few claimants have the resources to contest a case that can last more than ten years.

Some European governments have halted searches for the rightful owners of stolen artworks. According to Agnes Peresztegi, a Paris-based lawyer and president of the Commission for Art Recovery, France is at the forefront.

Some countries have started, she said. France has not even touched the surface.

French Ministry of Culture statistics reveal more than 60,000 stolen works of art were returned from Germany at the end of the war. Although over half were reclaimed by their original owners in the latter part of the 1940s, 25 percent were retained by France. About 13,000 of those were bought, with the proceeds going into the French treasury; the remaining pieces went to French museums.

Many remain on public display, marked with an anonymous ‘MNR,’ the French initials for ‘National Museums Recovery.’

In the mid-1990s, when then-President Jacques Chirac for the first time officially apologized for France’s role in the Holocaust, the French government launched an inquiry into the provenance of these works. Since compensation began in 1951, only 107 of the works retained by the French government have been relinquished, 79 from the MNR collection.

Progress has been delayed since then, primarily because the government does not have the money for intensive searches, say researchers. Despite an effort in recent years by French senator Corinne Bouchoux to reopen the restitution project, critics say not much has changed, Stars and Stripes reported.

What he would like, says Polack, is for there to be a positioned welcome center that could acquaint people who have questions, noting that many descendants are intimidated by the bureaucratic red tape associated with filing such a claim. It should be the honor of France to accomplish this, an honor for citizens to be involved in this; if there is ever the opportunity to repair, even by a slight amount, then is should be done.