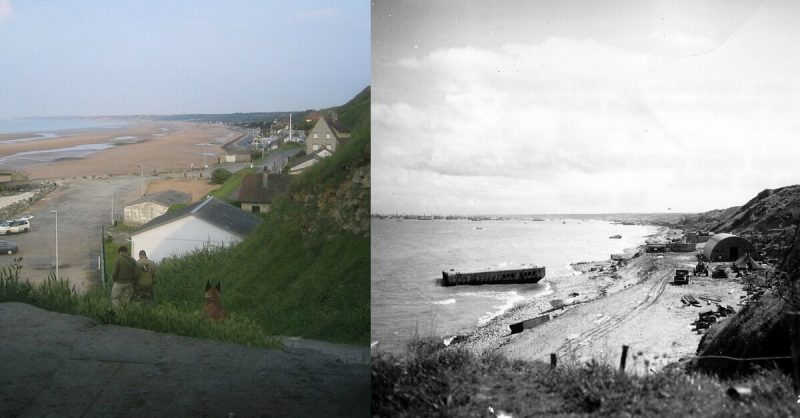

Today, Omaha Beach in Normandy, France looks like any other northern French coastal beach, with the lapping waves of the English Channel. However, over 71 years ago it was filled with the sight of thousands of American troops landing on the beach, being fought off by the German Soldiers.

Researchers have been excavating the beach to see what remnants of the battle they can find. Pieces of shrapnel, glass and iron can still be found just under the beach’s surface.

Two geologists, Earle McBride and Dane Picard, first visited Omaha beach in 1988. They took away a sample of sand for another project but found remnants of the D-Day invasion.

The geologists from the University of Texas, Austin, say that they should have thought that they would find war time artefacts, but the beach just looked like an ordinary beach, and there are no apparent war remnants there at all.

When the sand sample was initially examined back in the US, there was nothing to be found and other priority projects took over, before they could come back to it at a later date. When they did, they completed a full analysis and amongst the granules of sand were grains of metal thought to be fro shrapnel. Other elements included beads of glass and iron, which may have been caused by the explosions of mortar.

The scientists say that regular sand becomes round because it is constantly bashing other grains of sand. The iron elements, meanwhile, are of rust that must be from shrapnel thrown all over the beach by explosions. The actual beads of glass and iron were just 0.5 mm across. Around four percent of the entire sample was from shrapnel.

Landings at Omaha Beach were necessary in order to link up the British landings to the east at Gold with the American landing to the west at Utah, thus providing a continuous lodgement on the Normandy coast of the Bay of the Seine.

On D-Day, the untested 29th Infantry Division, along with nine companies of U.S. Army Rangers redirected from Pointe du Hoc, were to assault the western half of the beach. The battle-hardened 1st Infantry Division was given the eastern half. The initial assault waves, consisting of tanks, infantry, and combat engineer forces, were carefully planned to reduce the coastal defenses and allow the larger ships of the follow-up waves to land.

Opposing the landings was the German 352nd Infantry Division, a large portion of whom were teenagers, though they were supplemented by veterans who had fought on the Eastern Front. Of the 12,020 men of the division, only 6,800 were experienced combat troops, detailed to defend a 33 mi front.

Very little went as planned during the landing at Omaha. Difficulties in navigation caused the majority of landing craft to miss their targets throughout the day. The defenses were unexpectedly strong, and inflicted heavy casualties on landing U.S. troops. Under heavy fire, the engineers struggled to clear the beach obstacles; later landings bunched up around the few channels that were cleared.

Weakened by the casualties taken just in landing, the surviving assault troops could not clear the heavily defended exits off the beach. This caused further problems and consequent delays for later landings. Small penetrations were eventually achieved by groups of survivors making improvised assaults, scaling the bluffs between the most heavily defended points.

By the end of the day, two small isolated footholds had been won, which were subsequently exploited against weaker defenses further inland, thus achieving the original D-Day objectives over the following days.

The geologists say that the elements of the D-Day invasion won’t last in the beach’s sand forever, as coastal erosion takes place and the sea washes it out into the channel.