Nazi scientists developed an impressive arsenal of weapons during World War II. From nerve agents and weapons that spread disease, to the V-1 and V-2 rockets – the German scientists were at the forefront of weaponry.

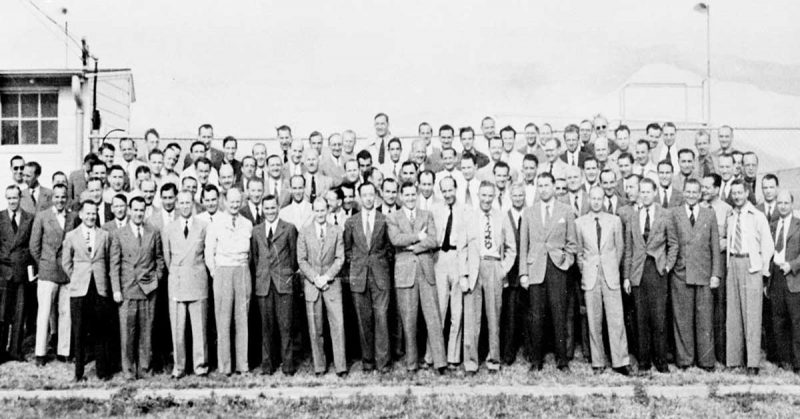

As the war wound down in 1945, the Americans and the Soviets began working to bring Nazi scientists to their countries to develop weapons for them. 71 years ago, 88 Nazi scientists landed in the USA and began working for the American government.

After Germany had surrendered, the American troops searched Germany for hidden weapons. American officials were shocked at what was found. Annie Jacobsen wrote about the American search for Nazi scientists in her book, “Operation Paperclip: The Secret Intelligence Program that Brought Nazi Scientists to America.”

She says that the American government and military leaders had no clue that the Nazis were developing a Bubonic plague weapon. That’s when they realized that they needed to get those weapons for themselves.

The Soviet Union was thinking the same thing, so there was a drive not to get left behind. They developed Operation Paperclip, a plan to bring 88 captured Nazi scientists to the USA and put them back to work for America.

The military tried to whitewash the past of their new recruits (or “prisoners of peace,” as the scientists called themselves) but some of them were involved in pretty troubling work for the Nazis. As an example, Wernher von Braun not only developed the V-2 rocket, but he had first-hand knowledge of the concentration camps and chose prisoners from the camps to work on his rockets.

The project was top secret. The government did not want it to be public knowledge that these men whose designs had killed so many people in Europe, on top of all the deaths caused by the government they were supporting, were working for the US. Even the agents in the Office of Special Investigations who tracked down Nazi officers after the war didn’t know the extent to which the government was working with them once they were captured, Smithsonian reported.

The contributions of these men were instrumental in advancing science in the US, including the Apollo space program. But the men making those contributions were tragically flawed; many supported the Nazi government and the Holocaust. The legacy of Operation Paperclip is questionable, at best.