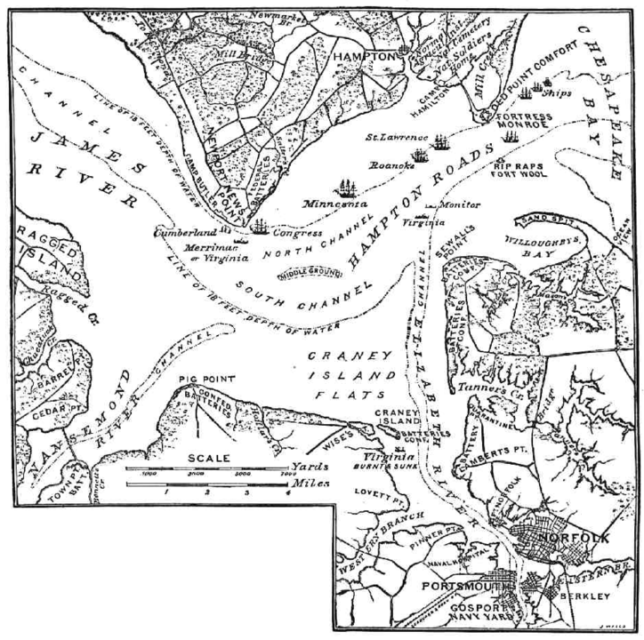

It was March 8, 1862, a Saturday. On the waters of Hampton Roads off Newport News, Virginia – where the Chesapeake Bay empties into the Atlantic Ocean – the Federal warships Cumberland and Congress bobbed easily on a light chop.

The sky was blue, the day warming, the morning uneventful. Drying wash flapped on a light breeze, harmonicas offered-up pleasant tunes, as sailors went about their usual duties. Then, abruptly, around 12:30 in the afternoon, all that changed.

Across the Bay, far to the south, emerging from the Elizabeth River at Norfolk, something odd, something never seen before, had just been spotted. Heads turned, fingers pointed, as binoculars and telescopic glasses were quickly yanked from their cases. A trail of black smoke could be seen rising from a smokestack, below that what appeared to be an enormous hull moving very slowly, bearing WNW.

“I wish you would take the glass and have a look over there, sir,” said the quartermaster of the watch. “I believe that thing is a-comin’ down at last.”

General Quarters was sounded. Drums beat the rhythm as men scurried cross decks, pulling down laundry, racing to the guns, preparing for battle. Truthfully, there was no rush. It would take almost an hour before the hulking mass would be near enough to spot the gun tubes that lined its casemate, or the iron that covered its hull.

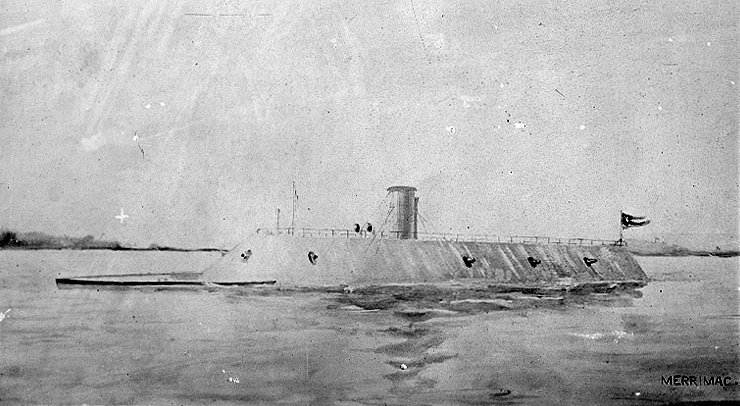

At that point there was no doubt, however, it was the rechristened USS Merrimack, clearly identifiable now by the Confederate, seven-star, blue naval jack flying from her stern. The Confederates had renamed her Virginia, but everyone – friend and foe alike – still called her Merrimack.

She had been joined by several vessels of the Confederacy’s James River Squadron – Raleigh, Beaufort, Jamestown, Patrick Henry, along with the tug, Teaser – all of them smaller, and far less formidable than the Merrimack.

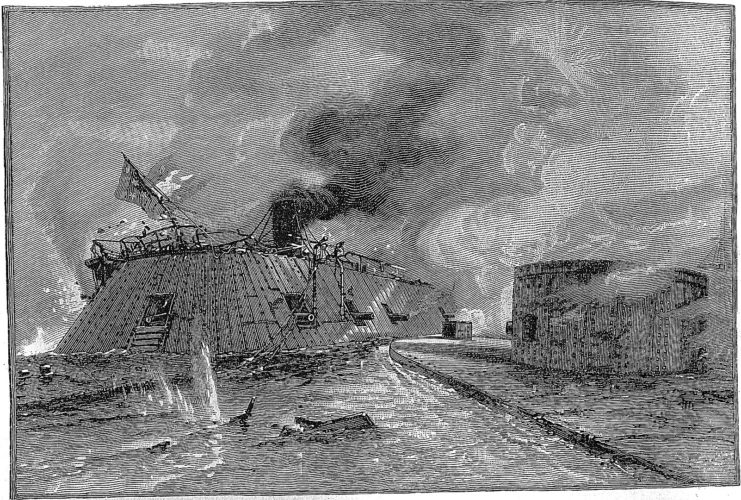

The Merrimack had been a frigate under construction at the Federal Navy’s yard in Norfolk at the beginning of the war. That yard was then put to the torch when the Navy decided to abandon Norfolk to the Confederacy, but much of the Merrimack survived the flames. Salvaged and retooled as an ironclad, the vessel, now a lumbering, iron monster with sloping sides, and a formidable collection of guns, looked far more like some leviathan risen from the deep, than any recognizable vessel of the day.

As Cumberland and Congress cleared decks for action, the other wooden ships of the North Atlantic Blockading Squadron – St. Lawrence, Roanoke, and Minnesota attempted to get underway and escape as quickly as possible. Cumberland, a powerful sloop-of-war, was the flagship of the Home Fleet, a wood-and-sail vessel of the Raritan-class. She had been recently streamlined and refitted with twenty-two 9” Dahlgren smoothbore cannon, one 10” Dahlgren, and a 70 lb. naval rifle – a daunting array of weaponry.

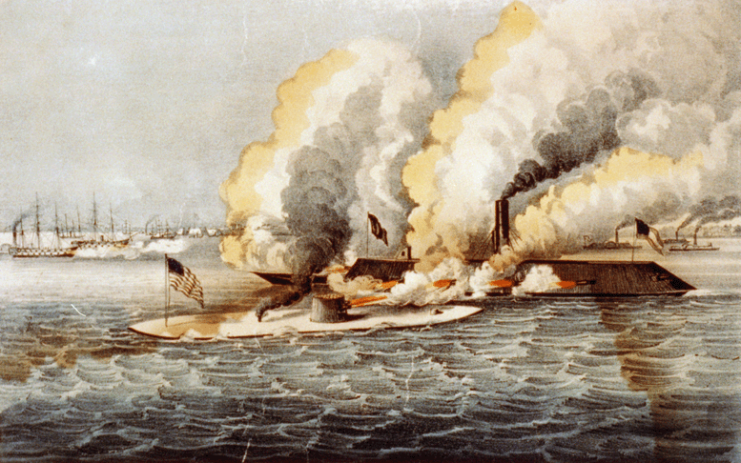

But the Merrimack – now armed with three 9” Dahlgren guns on each broadside, a Brooke rifle fore and aft, and an additional Brooke rifle on each broadside – appeared unimpressed. The ironclad churned-on slowly but steadily, straight at Congress, a wood and sail frigate bearing 48 32 pounder guns, and four 8” smoothbore cannon.

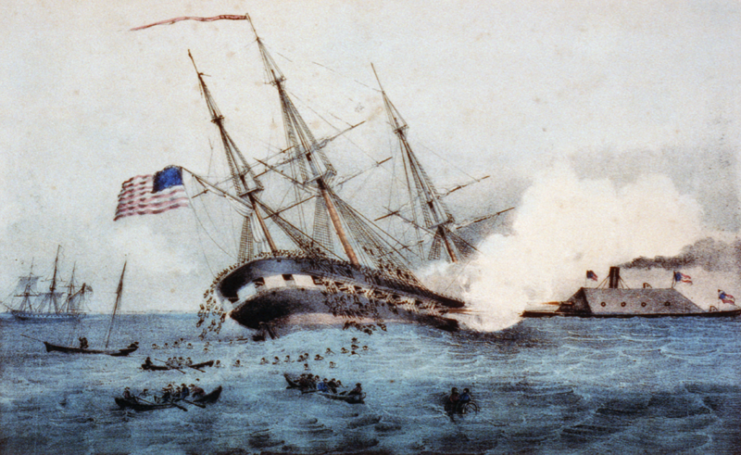

The crews of both Federal warships looked-on in amazement as Merrimack closed to within two hundred yards. “The Congress then fired a full broadside point-blank. Nine hundred pounds of hurtling metal smashed fully home. In horror the gunners saw the balls ricochet into the air likes pebbles off a roof.”

The Merrimack was not only unscathed by the broadside, but unfazed. Hardly a metal plate had been rattled loose. The ironclad then came about and unleashed a four-gun broadside, tearing Congress to pieces. Below decks, smoke billowed, men screamed, and blood pooled like water. The era of the wooden warship – an era that had reigned for at least five thousand years – had just been brought to an abrupt and frightful end. The age of the iron warship had dawned.

As Congress took on water, Merrimack came about, then headed straight for the Cumberland. Attached to her prow was an iron ram – a weapon not used widely since the days of Greece and Rome – with which she intended to dispatch the Federal sloop-of-war. The ironclad fired one shot with its forward gun which exploded below decks, then rammed Cumberland dead on the bow.

Mayhem reigned onboard the Federal sloop as the ironclad backed away full astern, turned slightly, and found a comfortable position just off Cumberland’s shattered bow where she raked the Federal warship with impunity. The Cumberland soon went-up in smoke and flames. That accomplished, the ironclad returned to the wounded Congress, which was trying to limp away to safety.

But Merrimack caught her easily and turned broadside. Raking the frigate from stem-to-stern, the ironclad simply tore her to shreds, and the Congress eventually blew to pieces when her magazines took fire.

By day’s end the Federal squadron had been virtually annihilated. Both Congress and Cumberland were on the bottom, while the other three Federal vessels had run aground in their haste to escape. For those looking on, it appeared the Confederacy had developed a superweapon.

Thus, as the Merrimack returned to its berth that evening –intent on returning the following morning to finish-off the stranded Federal squadron – it appeared the Confederacy had engineered a new weapon that would, not only break the Federal naval blockade, but revolutionize naval warfare entirely.

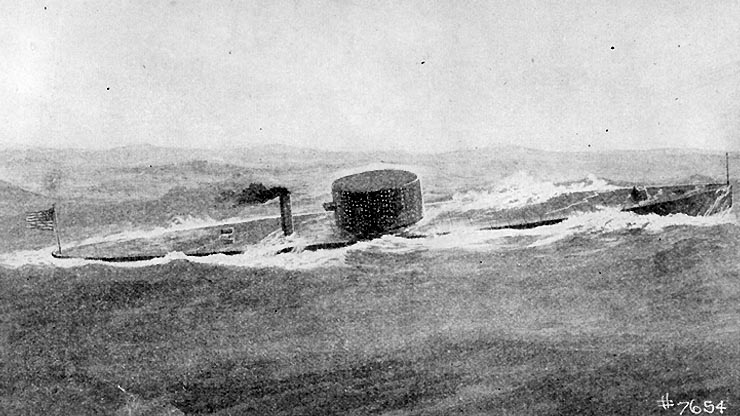

As the Merrimack slipped away on the evening tide, however – and unknown to everyone present – another ironclad was then steaming-up Bay. As if Neptune, with an eye for high drama, had written the script himself, this ironclad finally cut its engines, dropped anchor, and took-up a position in defense of the stranded Minnesota. It was, of course, the USS Monitor.

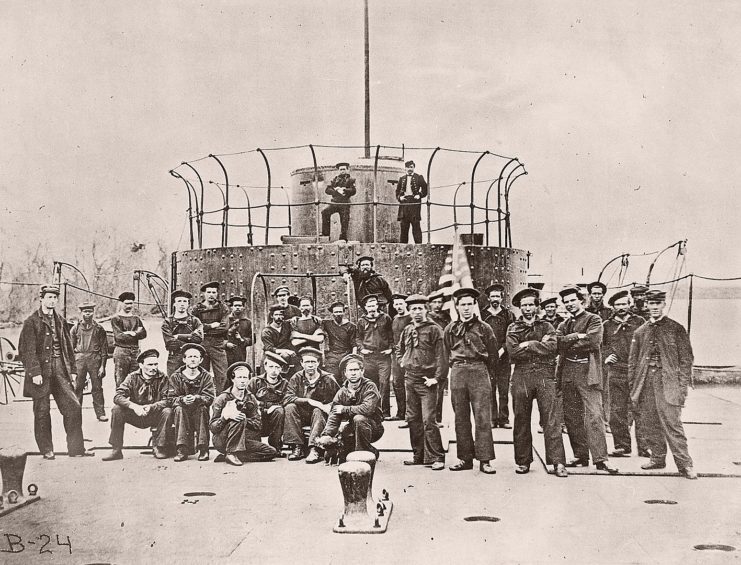

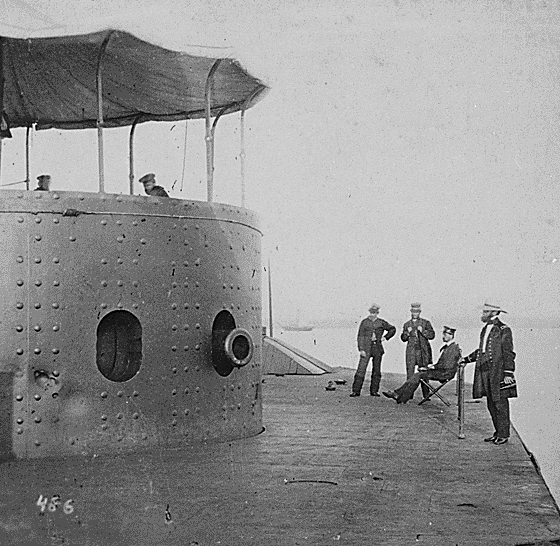

The brainchild of Swedish engineer John Ericsson, his design was so radical that initially the navy board hardly knew what to make of it. The Monitor was only 172’ in length, 41’ abeam. On the deck sat a small pilot house, a revolving turret sporting 2 11” Dahlgren naval rifles, and nothing more. Constructed on New York’s East River in just over 100 days, having received reports of the Merrimack’s imminent completion, Monitor had shoved-off for Virginia in early March.

Meanwhile, in Washington, President Lincoln, along with his cabinet, having received telegraphed reports of the prior day’s calamity, sat in benumbed silence. No one had the slightest idea what to do. Lincoln was reportedly so overwrought he could barely speak.

Secretary of War Edwin Stanton finally broke the silence, railing: “The Merrimack would sink every vessel in the navy, capture Fort Monroe, cut off Burnside in the Carolina sounds, retake Port Royal, and lay New York and Boston under ‘contribution.’” Then he threw-open a window, half-expecting to see the Merrimac steaming-up the Potomac River, presumably to open fire on the White House. According to Gideon Welles, then Secretary of the Navy, it was “the worst day of the war.”

The morning following the Merrimack’s frightening debut, March 9, the Confederate ram again journeyed across the Bay with the intention of destroying the stranded Minnesota, only to discover the tiny Monitor bobbing in the water like “a cheese on a raft,” gamely prepared to give battle. Much like a heavyweight fight, crowds jammed and jostled along the shoreline to watch as the spectacle unfolded.

The Merrimack opened the engagement with a broadside that flew high, and the Monitor returned fire, striking Merrimack, but doing little damage. Then, for hours-on-end, the combatants circled at close quarters, repeatedly scoring hits, but neither able to strike a decisive blow. Merrimack attempted to ram, but the more maneuverable Monitor dodged away, unharmed.

Damage was done to both vessels, but nothing disabling. In fact, at one point during the confrontation, the Merrimack’s guns fell oddly silent. Catesby Jones, the ironclad’s commander, inquired as to the pause. From the gundeck Lieutenant Eggleston responded wryly, “I find that I can do her as much damage by snapping my thumb at her every two minutes and a half.”

A shot finally struck the Monitor’s pilot house, momentary blinding the captain, and the vessel withdrew momentarily to make a change in command. It soon returned to combat, however, only to discover the Merrimack – thinking its foe had given-up the fight – departed. Both sides subsequently claimed victory, but there is little question the first clash of iron warships had ended in a draw.

Regardless of wins and losses, however, every wooden warship then in existence had been instantly rendered obsolete, naval blueprints altered forever. And while Merrimack had made a fine showing, it would be the gritty little Monitor with its low silhouette and revolving gun turret, that would inspire naval concepts of the future.

Indeed, it would not be overstatement to suggest that every battleship of the 20th Century – from Dreadnaught to Bismarck to Missouri – had direct bloodlines back to John Ericsson’s innovative design, and that on March 9, 1862 a page in the book of naval warfare had been emphatically turned.

Another Article From Us: Live Like a Bond Villain, 3 Remote Napoleonic-Era Forts For Sale

Jim Stempel is a speaker and author of nine books and numerous articles on American history, spirituality, and warfare. His newest book regarding the American Revolution – Valley Forge to Monmouth: Six Transformative Months of the American Revolution – will be released this fall. For a full preview, pricing, and pre-publication reviews, visit Amazon (https://amzn.to/34J4fZN) Or, visit his website (https://bit.ly/2EAWNVT) for all his books, reviews, articles, biography, and interviews.