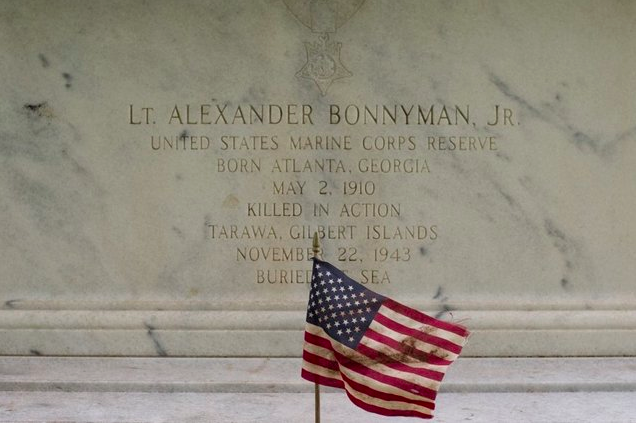

Just outside Knoxville, TX, in the Highland Memorial Park, stands a memorial for Lt. Alexander Bonnyman, JR. If you look closely at the photo you’ll see that Lt. Bonnyman’s remains are not in Tennessee as the bottom line reads, “Buried At Sea”. But Lt. Bonnyman’s remains were most definitely NOT “Buried At Sea”.

Lt. Bonnyman was killed in action during the 76 hours of hell that it took the US Navy, Marine Corps and Army to invade and overcome the entrenched 4500 strong Japanese contingent on a tiny Pacific atoll known as Tarawa in the chain of islands known as the Gilberts.

To carry the fight from Pearl Harbor to Japan, US military planners devised an island hopping campaign that took the US to many virtually unknown islands across the Pacific. After a bloody 7 month fight on Guadalcanal which was nearly lost, the US knew that their path to Japan went through the Mariana Islands. But to take the Mariana Islands, the Navy first had to capture the Marshall Islands. And you couldn’t take the Marshall Islands without first knocking out a Japanese air strip on the island of Tarawa in the Gilberts. So a successful push to Japan brought Tarawa directly into the crosshairs.

After a near disaster on Guadalcanal, much of 1943 was spent in building the strength of the US Navy and the Marine Corps. Hundreds upon hundreds of ships were built and thousands upon thousands of troops were trained.

Tarawa would be their first big test. So on November 20, 1943, a force of 35,000 Americans invaded Tarawa which was garrisoned by 4,500 Japanese who had been there building fortifications for more than a year.

The Japanese had installed four 8-inch Vickers howitzers purchased from Britain during the Russo-Japanese war which ended in 1905. 500 pillboxes with machine guns were built from sand, logs and concrete along with an additional 14 artillery pieces. All dug in and waiting for the Americans who the Japanese knew were certain to come.

The US invasion force arrived with 6 front line aircraft carriers and 11 smaller carriers. In support were 12 battleships, 8 heavy cruisers, 66 destroyers and 36 troop transports carrying the entire 2nd Marine Division and a significant part of the Army’s 27th Infantry Division.

As the force sailed over the horizon and into the view of the Japanese on Tarawa, the shore batteries opened fire. Returning fire against the four 8-inch guns were two US Battleships, the Maryland and Colorado, each blasting away with their much larger 16-inch guns. It wasn’t long before the Japanese guns were silenced and at that point, in the pre-dawn hours of November 20, one thousand guns of all calibers arrayed offshore on nearly 100 warships, opened fire on tiny Tarawa, a land mass of just 0.59 square miles. A person could hardly blame the Admirals in charge for thinking that no one could survive the massive barrage. They would be proven wrong as the Japanese had prepared deep underground bunkers with thick concrete to protect them from just such a barrage. They suffered very few casualties among the 4,500.

At 0900, the first landing craft began heading towards the beaches on the far side of a lagoon that had been cleared of mines. Unfortunately, the lagoon was surrounded by a high coral reef and due to an unusually low, high tide condition, the wood bottomed Higgins Boats could not clear the reef. A few tracked LVT “Alligators” were able to crawl over the coral reef and head towards the beaches. Sadly, these pre-war designed flimsy vehicles only had wooden sides and as they slowly crossed the lagoon towards the beach, the Japanese defenders, returning to their above ground positions opened fire on the LVT’s. Only a few made it to shore. Most were riddled by machine gun fire. Seeing the chaos, officers stuck on the reef decided to try to walk across the relatively shallow lagoon towards the beach rather than wait. Hundreds were gunned down in a withering crossfire from Japanese pillboxes on either side of the horseshoe shaped lagoon..

Eventually the Americans would land enough troops and equipment to overcome the Japanese. Before it was over, almost 1700 US Servicemen and 4,700 Japanese would die in a fight for this tiny spit of land that is smaller than 100 football fields.

One of the men who came ashore onTarawa was Lt. Alexander Bonnyman. He was unusual in that he was 33, rather old for a WW2 Marine. Being too old to be drafted, he volunteered for the Marines out of a sense of adventure. He had been on Guadalcanal and for his actions while fighting there , he received a battlefield commission 2nd Lieutenant. On Tarawa, he lead a squad whose job was to clear obstacles, usually with explosives.

on D-Day +1, the 2nd day of fighting, Bonnyman was with a group that was attacking across the airfield when they came upon a large concrete bunker. As they fought towards the front of the bunker, Bonnyman and his team encountered a large Japanese force. A major firefight broke out and Bonnyman’s squad began to run low on ammunition. They retreated to get more ammunition and quickly returned with Bonnyman in the lead. A massive fight ensued and eventually the Marines took the bunker with the Japanese suffering more than 150 killed. But the Japanese wanted the bunker back and counterattacked several times trying to push the Marines back. It was while fighting off one of these counterattacks that Lt. Bonnyman, leading from the front, was killed in action.

With Tarawa sitting near the equator, the remains of fallen soldiers needed to be buried quickly. Most of the dead on Tarawa were buried in a series of temporary graves that were long pits dug into the sand with the names of the fallen and the location of the burial pit recorded by the graves registration people. Lt. Bonnyman was placed with 34 others in a burial pit near the dock in the lagoon.

After the fighting was over, the Marines and everyone else quickly left Tarawa to prepare for the next battle. It wasn’t until 1946 that graves registration crews from the US military returned to exhume the bodies of the remaining 500 US servicemen still in temporary graves around tiny Tarawa. Try as they might, they could not find the pit that contained Lt. Bonnyman and his 34 comrades, The men in that location and several hundred more in other lost locations around the atoll were declared “unrecoverable” by the Quartermaster General’s Office in 1949. It was at this time that Bonnyman’s family was told that he had been “Buried at Sea”.

In 1947, Lt. Alexander Bonnyman was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Then Secretary of the Navy, James Forrestal presented the Medal to Bonnyman’s daughter who accepted it on behalf of family. Bonnyman was one of four who were awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor for their bravery on Tarawa. Only Bonnyman’s remains were never found.

According to Bonnyman’s grandson, Clay Bonnyman Evans of Niwot Colorado, the family never recovered from Alexander’s death. Alexander’s parents died never quite accepting the fate of their son. At the family burial plot in Tennessee, the family erected the memorial inscribed with Alexander Bonnyman’s name and the fact that he had been “Buried at Sea”.

That would have been the end of the story were it not for an organization called History Flight, an NGO that offers individuals an opportunity to fly in vintage WW2 aircraft and funds their own search efforts for American MIA servicemen around the world in coordination with the Defense POW/MIA Acccounting Agency of the US Government. History Flight’s founder Mark Noah became interested in the missing men on Tarawa when he was searching for a downed plane in the Tarawa lagoon in 2006. In 2008, they returned to the island with ground penetrating radar to locate as many burial sites as they could find. Since then, teams from History Flight have recovered the remains of nearly 120 individuals.

Earlier this year, Clay Bonneyman Evans returned to Tarawa with one of the teams that thought they had found the pit that might contain the remains of his grandfather. Sure enough, as the forensic archeologists slowly uncovered first one set of remains and then another, the remains of Alexander Bonnyman were also revealed. Bonnyman’s identification was easy compared to most for he had a number of gold teeth, something quite unusual amongst the much younger typical Marines who fought during WW2. A forensic lab in Hawaii confirmed his identity with a DNA match.

Bonnyman’s daughters have decided to reinter Alexander with his parents, 2 brothers and 1 sister at the family plot in Knoxville at a ceremony to be held this September. With this, a 70 year mystery will also be put to rest.

Medal of Honor citation

The President of the United States takes pride in presenting the MEDAL OF HONOR posthumously to

FIRST LIEUTENANT ALEXANDER BONNYMAN, JR. UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS RESERVE

for service as set forth in the following CITATION:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty as Executive Officer of the 2d Battalion Shore Party, 8th Marines, 2d Marine Division, during the assault against enemy Japanese-held Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands, 20–22 November 1943. Acting on his own initiative when assault troops were pinned down at the far end of Betio Pier by the overwhelming fire of Japanese shore batteries, 1st Lt. Bonnyman repeatedly defied the blasting fury of the enemy bombardment to organize and lead the besieged men over the long, open pier to the beach and then, voluntarily obtaining flame throwers and demolitions, organized his pioneer shore party into assault demolitionists and directed the blowing of several hostile installations before the close of D-day. Determined to effect an opening in the enemy’s strongly organized defense line the following day, he voluntarily crawled approximately 40 yards forward of our lines and placed demolitions in the entrance of a large Japanese emplacement as the initial move in his planned attack against the heavily garrisoned, bombproof installation which was stubbornly resisting despite the destruction early in the action of a large number of Japanese who had been inflicting heavy casualties on our forces and holding up our advance. Withdrawing only to replenish his ammunition, he led his men in a renewed assault, fearlessly exposing himself to the merciless slash of hostile fire as he stormed the formidable bastion, directed the placement of demolition charges in both entrances and seized the top of the bombproof position, flushing more than 100 of the enemy who were instantly cut down, and effecting the annihilation of approximately 150 troops inside the emplacement. Assailed by additional Japanese after he had gained his objective, he made a heroic stand on the edge of the structure, defending his strategic position with indomitable determination in the face of the desperate charge and killing 3 of the enemy before he fell, mortally wounded. By his dauntless fighting spirit, unrelenting aggressiveness and forceful leadership throughout 3 days of unremitting, violent battle, 1st Lt. Bonnyman had inspired his men to heroic effort, enabling them to beat off the counterattack and break the back of hostile resistance in that sector for an immediate gain of 400 yards with no further casualties to our forces in this zone. He gallantly gave his life for his country.