The common thread of history winds through battles and wars, and the last battle of the American Indian Wars was not at Wounded Knee on December 28th, 1890 as the official record states. Instead, this thread ends in the knot at Bear Valley, near the Arizona border with Mexico, on January 9th, 1918.

Over the span of the thirty year period between the two dates, the Army and small groups of Native Americans across the west engaged in semi-regular skirmishes.

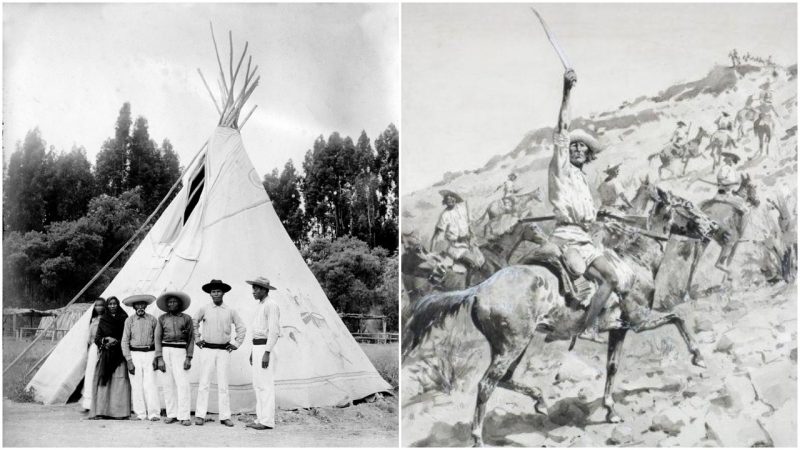

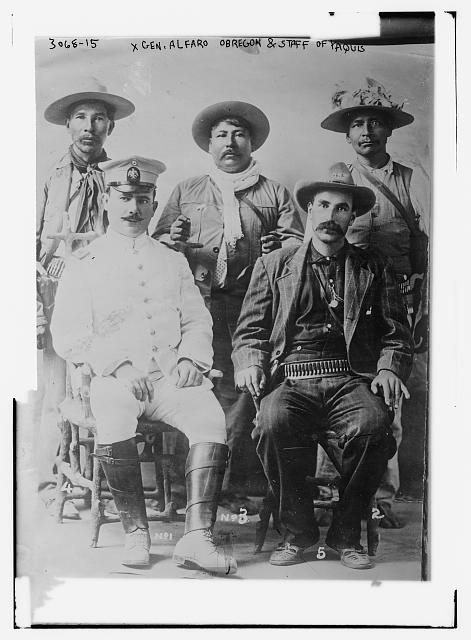

The final battle at Bear Valley was actually a continuation of an earlier conflict between the Yaqui people of Sonora, who were fighting for an independent Mexican homeland. It was a war that had been waged by these people for decades until it was absorbed by the exploits of the larger Mexican Revolution.

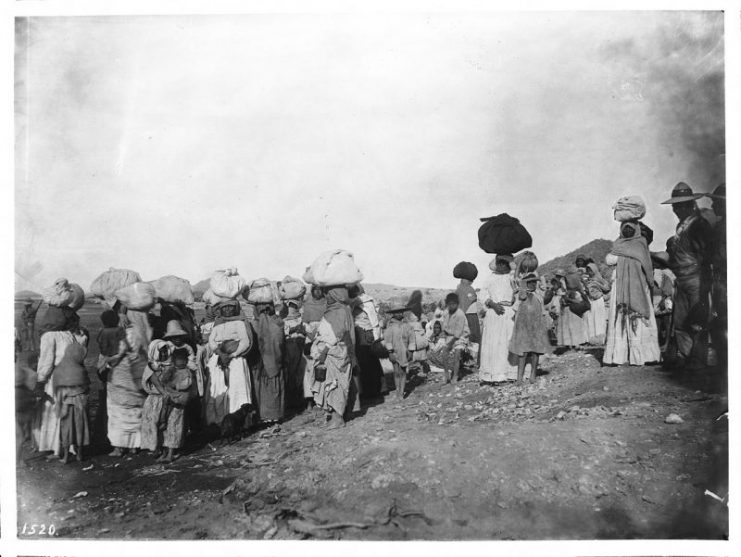

Many of the Yaqui people regularly crossed the borders into the United States to find work on the cotton farms of southern Arizona, after which they would spend the money they earned on firearms and ammunition to continue the war.

In 1917, General Plutarco Elias Calles, military governor of Sonora, made an informal request for American help in stopping the cross border arms trade. Simultaneously, cattle ranchers complained about the Yaqui bands trespassing on their lands and periodically killing stray cattle for either food, or hides to make crude sandals to better make the journey across the desert.

Most of the United States Army was still mired up to its neck in France fighting in the Great War, but the Buffalo Soldiers of the 10th Cavalry stayed home. After watching just how the British cavalry fared against the German machine guns early in the first world war, the army decided to leave their cavalry at home in the U.S.

That meant that the cavalry were free to see to the cross border trade, and that’s exactly what they did. Arizona subdistrict commander, Colonel J.C. Friers of the 35th Infantry put his men and those of the 10th into position along the border to attempt to stall the arms smugglers.

It was early in January of 1918 when Captain Frederick H.L. “Blondy” Ryder had thirty of the men of Troop E take the Bear Valley position in an abandoned rancho on a high ridge. It was a decently adroit strategic move, as the high rock formation provided a panorama view of their surroundings.

On the eighth of January, they got their first bit of information about the movements of the Yaqui from a local cattleman, who reported that his neighbor had found a fresh beef kill with parts of its hide stripped away to make sandals.

First Lieutenant William Scott took a detail and reinforced the observation post, and about mid-day on the 9th, Scott relayed using hand signals that the Yaqui were in sight and moving. They were gone by the time troopers had saddled up, but Scott followed them and relayed their changed position.

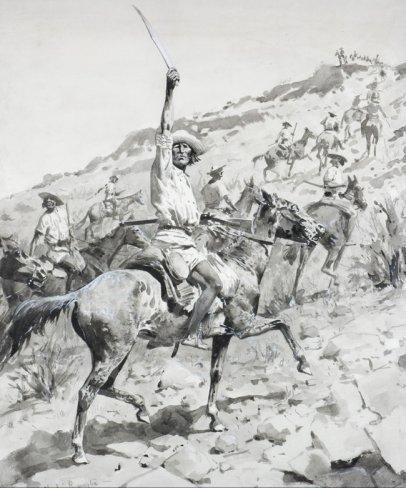

Near their objective, the troopers dismounted and advanced in a skirmish line. Captain Ryder thought he’d lost contact and was about to return to the horses when he stumbled on some abandoned packs. They were right on top of the Yaqui. He reformed his skirmish line and advanced, and soon they were under rifle fire.

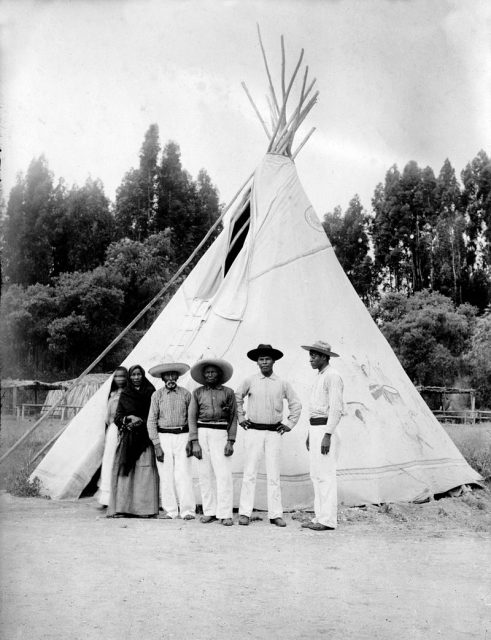

The Yaqui used their environment to maximum effect, drawing back and hiding behind boulder and brush, falling back and keeping behind cover while firing rapidly. The Yaqui offered the cavalrymen a fleeing target while the troops continued their inexorable advance.

Casualties were light because of the excellent cover, but soon the troopers overwhelmed the small rear guard charged with covering the Yaqui retreat into Mexico.

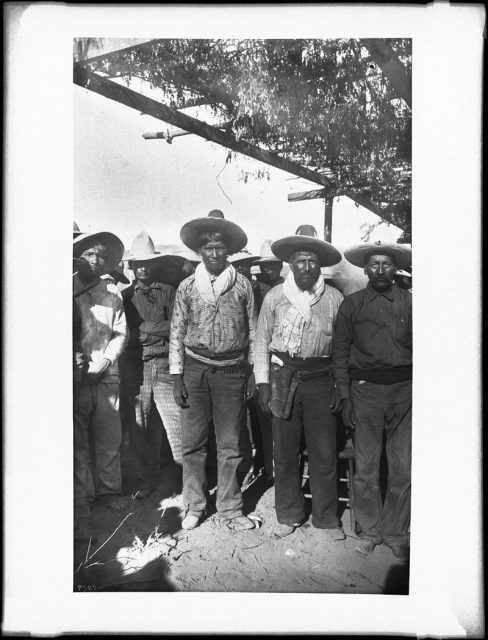

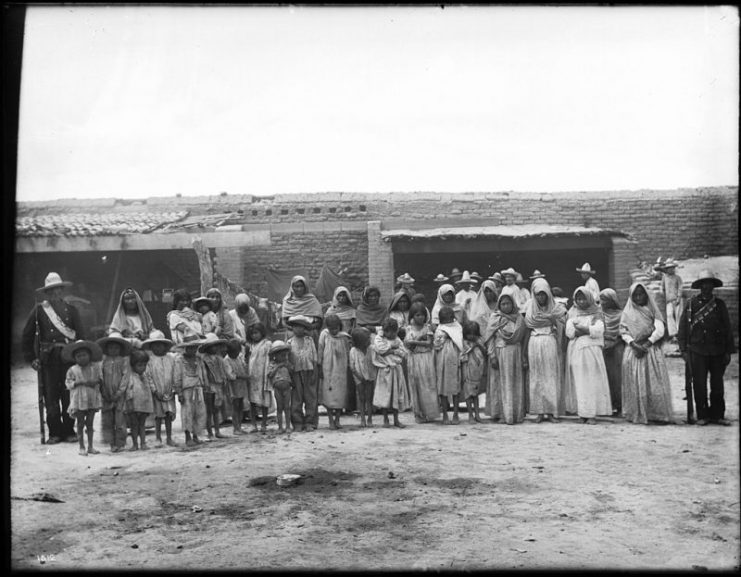

In the end, there were ten captives. The Yaqui admitted under questioning that they only fired on the American soldiers because they thought they were Mexican, and that they would have surrendered immediately if they had known their aggressors were American.

The Yaqui were held at Nogales for weeks prior to trial, where they engaged in everyday life of the common soldier, until finally they were transported to Tucson on orders from Washington, and they were charged with “wrongfully, unlawfully, and feloniously exporting to Mexico certain arms and ammunition, to wit: 300 rifle cartridges and about 9 rifles without first procuring an export license issued by the War Trade Board of the United States.”

The Yaquis plead guilty, and the men were sentenced to thirty days in jail. Overall, the Yaqui were pleased with the outcome, as their punishment in Mexico if they were deported would have been execution.

After this, the Yaqui disappear from history, only to resurface for a final time in 1928, when the Mexican army crushed them in an offensive that used heavy artillery, machine guns, armored cars and aircraft.