Because of proposed cuts in the United States budget for 2019, the National Park Services would be severely reduced. This may have a negative impact on many NPS sites including those where Japanese Americans were confined following America’s entry into WWII in 1941.

In 2006, the government set up the Japanese American Confinement Sites Grants Program via the National Parks and set aside thirty-eight million dollars to educate the public as to the importance of remembering this sometimes controversial story in the nation’s history.

The grant money is typically used for site preservation, research, preserving oral and written histories, museums, educational materials, and archeology.

As the years go by, fewer and fewer formerly incarcerated Japanese Americans are left to tell the stories. In order to keep those stories from fading away, work must be done and that costs money.

According to Bruce Embrey, co-chair of a committee from the largest detention center, Manzanar, “Ever since Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act in 1988, every sitting president has worked to make sure this story of what happened to Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War II was in everyone’s minds.

Every president except the current president has made sure that the lessons from a xenophobic, racist law not be lost on our country.”

Most of the Japanese Americans affected were living in the western states and many eastern dwelling residents didn’t even know it was happening.

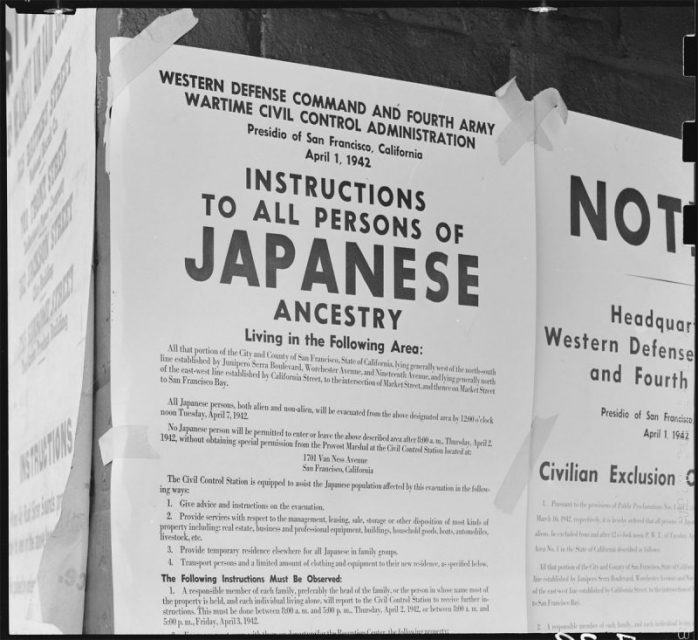

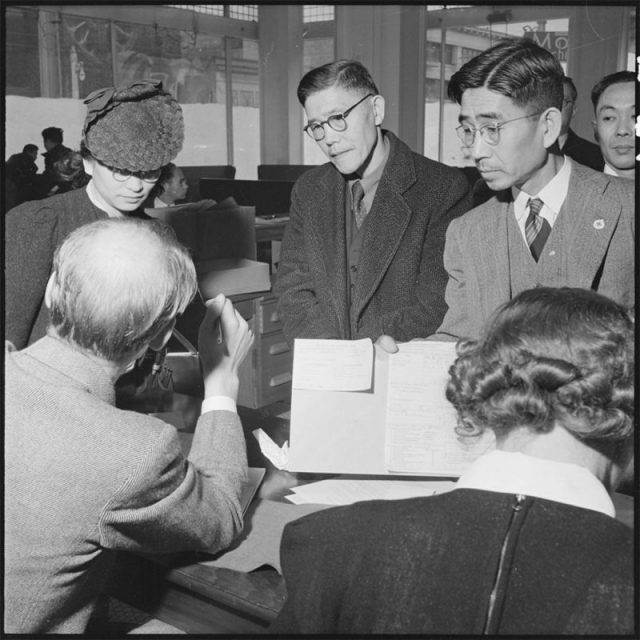

One hundred and twenty thousand Americans of Japanese descent were removed from their homes and forced into detention camps because their loyalties were in question simply because of their physical features. Most were hard-working people, born in the United States, who owned homes and lived quiet lives trying to make sure their children had a future.

When they were detained, they lost their homes, jobs, and any type of financial security they had earned. They were crowded into one of ten internment camps and forced to share tar paper shacks. Most of the camps were surrounded by barbed wire fencing with armed guard towers just as the Jews and Poles were experiencing in Germany.

If any of the inmates complained, they were sent to a camp set aside especially for those believed to be “disloyal” in Tule Lake, California. In Washington State, many families were temporarily housed in cow or horse stalls at the local fairgrounds until they were able to be sent to a permanent internment camp.

It all started when President Franklin D. Roosevelt succumbed to the national hysteria after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. He signed Executive Order 9066 giving the United States the right to detain anyone of Japanese descent.

In truth, the order was partly designed to protect the Japanese Americans from members of the public who turned against them making the assumption that because the attack on Pearl Harbor was carried out by Japanese, all Japanese must be bad.

The attitude in some ways parallels the present plight of Muslims in the U.S. who are being punished just because people who shared their ancestry or religion flew airplanes into the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. As one former prisoner commented, “If we were put there for our protection, why were the guns at the guard towers pointed inward, instead of outward?”

Fortunately, many influential activists are now speaking out. These include writer Tamiko Nimura, whose father was incarcerated at Tule Lake, Satsuki Ina, a psychotherapist, professor and filmmaker who was actually born at Tule Lake camp, educator Larry Matsuda, born at Camp Minidoka, and actor and writer George Takei, who spent much of his childhood in detention camps in Rohwer, Arkansas and Tule Lake.

Takei co-wrote and starred in Allegiance, a Broadway show that was based on his family’s experience during the war. Nimura and Matsuda have both published novels documenting the internment camp experience.

“This happened to us, and the language that’s being used today is very similar to what ultimately led to our incarceration,” said Satsuki Ina. “If the story of the Japanese Americans could be taught in the schools and public places where people could come and visit and see for themselves, it will educate people to keep it from happening again, to realize that we’re edging towards another dangerous violation of civil rights.”