It reads more like the unbelievable exploits of the Terminator. But the remarkable heroics ofLieutenant-General Sir Adrian Paul Ghislain Carton de Wiart are entirely true.

In what many are describing as the best Wikipedia entry ever, the soldier’s page opens with the following paragraph: ‘Sir Adrian Paul Ghislain Carton de Wiart VC, KBE, CB, CMG, DSO (5 May 1880 – 5 June 1963) was a British Army officer of Belgian and Irish descent.

‘He served in the Boer War, First World War, and Second World War; was shot in the face, head, stomach, ankle, leg, hip, and ear; survived a plane crash; tunnelled out of a POW camp; and bit off his own fingers when a doctor refused to amputate them.

‘He later wrote that “Frankly I had enjoyed the war” when describing his service in the First World War.’

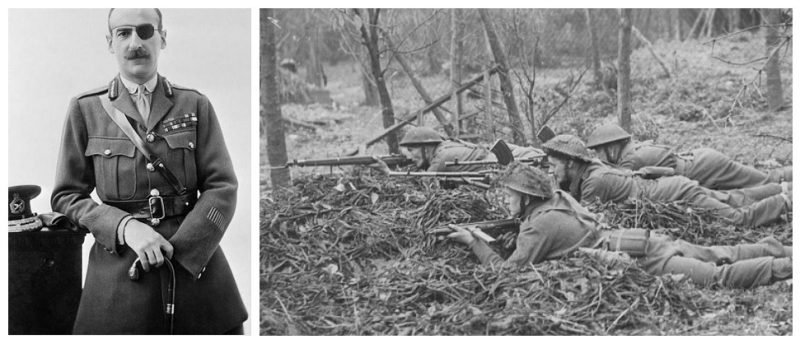

Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart was a one-eyed, one-handed war hero who fought in three major conflicts across six decades, surviving plane crashes and PoW camps. His story is like something out of a Boy’s Own comic.

Carton de Wiart served in the Boer War, World War One and World War Two. In the process he was shot in the face, losing his left eye, and was also shot through the skull, hip, leg, ankle and ear. In WW1 he was severely wounded on eight occasions and mentioned in despatches six times.

Having previously lost an eye and a hand in battle, Carton de Wiart, as commanding officer, was seen by his men pulling the pins of grenades out with his teeth and hurling them with his one good arm during the Battle of the Somme, winning the Victoria Cross.

WW1 historian Dr Timothy Bowman believes Carton de Wiart’s example helps debunk some myths.

“His story serves to remind us that not all British generals of WW1 were ‘Chateau Generals’ as portrayed in Blackadder. He exhibited heroism of the highest order.

“Evelyn Waugh supposedly used Carton de Wiart as the model for his fire-eating fictional creation, Brigadier Ritchie Hook, but Waugh’s fictional creation experienced considerably fewer adventures than his real life counterpart.”

It says much for Carton de Wiart’s character that despite being one of the most battle-scarred soldiers in the history of the British Army, he wrote in his autobiography: “Frankly, I had enjoyed the war.”

He was born into an aristocratic family in Brussels on 5 May 1880. In 1891 he was sent to boarding school in England, going on to study law at Oxford.

In 1899 he saw the opportunity to experience his first taste of war. Abandoning his studies, he left for South Africa to serve as a trooper in the British Army during the second Boer War. As he was under military age, wasn’t a British subject and didn’t have his father’s consent, he pretended to be 25 and signed up under a pseudonym. It was a baptism of fire which ended with him receiving bullet wounds to the stomach and groin, necessitating a return to England. Although eager to get back in the mix again, he had to wait more than a decade to experience further front-line action.

At the outbreak of WW1 in November 1914, Carton de Wiart, now naturalised as a British subject, was serving with the Somaliland Camel Corps, fighting the forces of the Dervish state. During an attack on an enemy stronghold, he was shot in the arm and in the face, losing his left eye and part of his ear. He received the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for his exploits. Speaking in 1964 Lord Ismay, who served alongside Carton de Wiart in Somaliland, described the incident:

“He didn’t check his stride but I think the bullet stung him up as his language was awful. The doctor could do nothing for his eye, but we had to keep him with us. He must have been in agony.” Lord Ismay also gave an insight into Carton de Wiart’s innate love of fighting:

“I honestly believe that he regarded the loss of an eye as a blessing as it allowed him to get out of Somaliland to Europe where he thought the real action was.”

Carton De Wiart was awarded the Victoria Cross for actions at La Boiselle.

He returned to England to recover in a nursing home in Park Lane. He was to return to this same place on each subsequent occasion he was injured. This became such a regular occurrence that they kept his own pyjamas ready for his next visit.

While recuperating from these injuries, Carton de Wiart received a glass eye. It caused him such discomfort that he allegedly threw it from a taxi and instead acquired a black eye patch.

Such setbacks were not to delay him long. He soon realised his ambition to fight on the Western Front when he was sent to Ypres in May 1915.

During the Second Battle of Ypres, the Germans launched an artillery barrage in which Carton de Wiart’s left hand was shattered. According to his autobiography, Happy Odyssey, he tore off two fingers when the doctor refused to amputate them. His hand was removed by a surgeon later that year.

The way he overcame injury and disability remains an inspiration, says Colour Sgt Thomas O’Donnell, who served in Afghanistan with the 1st Battalion Scots Guards. “For him to have endured all those injuries and gone through so much rehabilitation in so many conflicts and to never give up is really inspirational, particularly given the inferior medical facilities they had then. I just don’t know how he managed it.

“Soldiers like Carton de Wiart are a real example for troops serving today. It’s quite sad that having sacrificed so much his story isn’t particularly well-known. I think as well as remembering the war dead, it is vital we remember what injured soldiers like him went through in countless conflicts.”

After a period of recovery, Carton de Wiart once more managed to convince a medical board he was fit for battle. In 1916, he took command of the 8th Battalion, Gloucestershire Regiment, and while commanding them at the Somme his legend was cemented.

He electrified his men. The eye patch, empty sleeve and striking moustache, combined with his bravery, made him famous, with men under his command describing his presence as helping to alleviate their fear before going over the top.

During fierce fighting, the battle for the village of La Boiselle swayed back and forth. When three other commanding officers were killed, Carton de Wiart took charge of all units fighting in the village and led from the front, holding off enemy counterattacks.

He received the Victoria Cross, the highest British military award for gallantry, for his actions at La Boiselle. He, however, declined to even mention the medal in his autobiography, later telling a friend that “it had been won by the 8th Glosters, for every man has done as much as I have”.

“They shifted us from Ypres then back on the Somme again to the Devil’s Wood, and that’s where the old man got shot through the back of the head. But fortunately it missed his spinal cord.”

Some historians have contended that Carton de Wiart’s bravery at times bordered on recklessness, and that this may have explained his being passed over for promotion to divisional command in WW1.

But Bowman believes there were mitigating factors. “He was a brave soldier and effective leader of men. He was well qualified to hold divisional command, but so were many others, and his habit of turning up in the front line and getting himself injured didn’t bode well for his ability to manage a division.

Carton de Wiart lived in Poland for most of the inter-war period but his military career was not yet over. When World War Two broke out, he led a campaign in Norway in 1940 and was briefly stationed in Northern Ireland.

In April 1941 he was dispatched to form a British military mission in Yugoslavia, but his aircraft was shot down over the Mediterranean. After swimming to shore, he was captured by the Italians. Despite being in his 60s, he made numerous attempts to escape the PoW camp, on one occasion eluding recapture for eight days – quite a feat given his distinctive appearance and lack of Italian.

Painting by Sir William Orpen, 1919 (National Portrait Gallery, London)

Prisoner of war in Italy (1941–1943)

Carton de Wiart was a high profile prisoner. After four months at the Villa Orsini at Sulmona, he was transferred to a special prison for senior officers at Castello di Vincigliata. There were a number of senior officer prisoners here because of the successes made by Rommel in North Africa early in 1941. Carton de Wiart made friends, especially with General Sir Richard O’Connor, Thomas Daniel Knox, 6th Earl of Ranfurly and Lieutenant-General Philip Neame VC. In letters to his wife, Ranfurly described Carton de Wiart in captivity as “… a delightful character” and said he “…must hold the record for bad language.” Ranfurly was “…endlessly amused by him. He really is a nice person – superbly outspoken.”

The four were committed to escaping. He made five attempts including seven months tunneling. Once Carton de Wiart evaded capture for eight days disguised as an Italian peasant (which is surprising considering that he was in northern Italy, couldn’t speak Italian, and was 61 years old, with an eye patch, one empty sleeve and multiple injuries and scars). Ironically, Carton de Wiart had been approved for repatriation due to his disablement, but notification arrived after his escape. As the repatriation would have required that he promise not to take any further part in the war, it is probable that he would have declined anyway.

Then, in a surprising development, Carton de Wiart was taken from prison in August 1943 and driven to Rome. The Italian government was secretly planning to leave the war and wanted Carton de Wiart to send the message to the British Army about a peace treaty with the UK. Carton de Wiart was to accompany an Italian negotiator, General Giacomo Zanussi, to Lisbon to meet Allied contacts to facilitate the surrender. But to keep the cover, Carton de Wiart was told he needed civilian clothes. Distrusting Italian tailors, he stated that “[he] had no objection provided [he] did not resemble a gigolo.” In Happy Odyssey, he described the resultant suit as being “as good as anything that ever came out of Savile Row.” When they reached Lisbon, Carton de Wiart was released and made his way to England, reaching there on 28 August 1943.

China mission (1943–1947)

Within a month of his arrival back in England, Carton de Wiart was summoned to spend a night at the Prime Minister’s country home at Chequers. Churchill informed him that he was to be sent to China as his personal representative. He was granted the rank of acting lieutenant-general on 9 October, and left by air for India on 18 October 1943.

As his accommodation in China was not ready, Carton de Wiart spent time in India getting an understanding of the situation in China, especially being briefed by a genuine tai-pan, John Keswick, head of the great China trading empire Jardine Matheson. He met the Viceroy, Field Marshal Viscount Wavell and General Sir Claude Auchinleck, the Commander-in-Chief in India. He also met Orde Wingate.

Before arriving in China, Carton de Wiart attended the 1943 Cairo Conference organized by Churchill, U.S President Roosevelt and Chinese General Chiang Kai Shek. There is a famous picture of these leaders gathered in a Cairo garden, with Carton de Wiart standing behind them in company.

When in Cairo, he took the opportunity to renew his acquaintance with Hermione, Countess of Ranfurly, the wife of his friend from prisoner of war days, Dan Ranfurly. Carton de Wiart was one of the few to be able to work with the notoriously difficult commander of US forces in the China-Burma-India Theatre, U.S Army General Joseph Stilwell.

He arrived in the headquarters of the Nationalist Chinese Government, Chungking (Chongqing), in early December 1943. For the next three years, he was to be involved in a host of reporting, diplomatic and administrative duties in the remote war time capital. He worked with Chiang kai-Shek and when he finally retired he was offered a job by Chiang.

Carton de Wiart’s impressive array of medals. L to R, top row: Star badge, Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire; Badge, Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the British Empire; Companion of the Order of the Bath; Companion of the Order of St. Michael and St. George; Knight of the Legion d’Honneur.

Bottom row: Victoria Cross; Distinguished Service Order; Queen’sSouth Africa Medal, with clasps: South Africa 1901, Transvaal, Orange Free State, Cape Colony; Africa General Service Medal, with clasp Shimber Berris, 1914-15; 1914 Star; British War Medal, 1914-20; Allied Victory Medal, with oak leaf for Mention in Dispatches, 1914-19; France and Germany star; Africa Star; Burma Star; Italy Star; British War Medal, 1939-45; Coronation Medal, 1937; Coronation Medal, 1953; Officer of the Belgian Order of the Crown; silver Cross of the Polish Order of Military Virtue; Belgian Croix de Guerre (WWI); Polish Cross of Valour (WWI); Polish Cross of Valour (WWII); French Croix de Guerre (WWII), with oak leaf for Mention in Dispatches.

Carton de Wiart in Cairo, 1943

He regularly flew out to India to liaise with British officials. His old friend, Richard O’Connor, had escaped from the Italian prisoner of war camp and was now in command of British troops in eastern India. The Governor of Bengal, the Australian Richard Casey, became a good friend, his wife having nursed Carton de Wiart on one of his many hospital visits in World War I.

On 9 October 1944, Carton de Wiart was promoted to temporary lieutenant-general and to the war substantive rank of major-general.Carton de Wiart returned home in December 1944 to report to the War Cabinet on the Chinese situation. He was appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire (KBE) in the 1945 New Year Honours. Clement Attlee, when he became head of the Labour Government in June 1945, asked Carton de Wiart to stay on in China.

South East Asia

Carton de Wiart was assigned to a tour of the Burma Front, and after meeting Admiral Sir James Somerville, Commander-in-Chief of the British Eastern Fleet, he was given a front seat on the bridge of the battleship HMS Queen Elizabeth for the bombardment of Sabang in the Netherlands East Indies in 1945, including air battles between Japanese fighters and British carrier aircraft. It was the first time HMS Queen Elizabeth had fired her guns in anger since the Dardanelles in 1915.

A good part of Carton de Wiart’s reporting had to do with the increasing power of the Chinese Communists. The historian Max Hastings writes: “De Wiart despised all Communists on principle, denounced Mao Zedong as ‘a fanatic’, and added: ‘I cannot believe he means business’. He told the British cabinet that there was no conceivable alternative to Chiang as ruler of China.” He met Mao Zedong at dinner and had a memorable exchange with him, interrupting his propaganda speech to criticise him for holding back from fighting the Japanese for domestic political reasons. Mao was briefly stunned, and then laughed.

After the Japanese surrender in August 1945, Carton de Wiart flew to Singapore to participate in the formal surrender. After a visit to Peking, he moved to Nanking, the now liberated Nationalist capital, accompanied by Julian Amery, the British Prime Minister’s Personal Representative to Chiang.

A visit to Tokyo to meet General Douglas MacArthur came at the end of his tenure. He was now 66 and ready to retire, despite the offer of a job by Chiang. Carton de Wiart retired in October 1947, with the honorary rank of lieutenant-general.

Retirement and death

En route home via French Indochina, Carton de Wiart stopped in Rangoon as a guest of the army commander. Coming down stairs, he slipped on coconut matting, fell down, broke his back and several vertebrae, and knocked himself unconscious. He eventually made it to England and into a hospital where he slowly recovered. The doctors succeeded in extracting an incredible amount of shrapnel from his old wounds. He recovered and then went to Belgium to visit relatives.

His wife died in 1949 and in 1951, at the age of 71, he married Ruth Myrtle Muriel Joan McKechnie, a divorcee known as Joan Sutherland, a woman 23 years his junior (born in late 1903, she died 13 January 2006 at the age of 102), and settled at Aghinagh House, Killinardish, County Cork, Ireland, taking up a life pursuing salmon and snipe.

Carton de Wiart died at the age of 83 on 5 June 1963. He left no papers. He and his wife, Joan, are buried in Caum Churchyard just off the main Macroom road. The grave site is just outside the actual graveyard wall on the grounds of his own home Aghinagh House. Carton de Wiart’s will was probated in Ireland at £4,158 and in England at £3,496.

On the 2nd/3rd July 1916, he was awarded the VC. His citation reads:

“He displayed conspicuous bravery, coolness and determination in forcing home the attack, thereby averting a serious reverse. After the other Battalion Commanders had become casualties, he controlled their commands as well, frequently exposing himself to the intense barrage of enemy fire. His energy and courage was an inspiration to us all.”