The rural English village of Burwash in the county of Sussex is well-known because of its association with Rudyard Kipling. The famous author of ‘The Jungle book’ written in 1894, when Kipling was living in Vermont, Canada, and the poem ‘If’, published in 1910.

Like so many English villages, Burwash saw many of its young men march off to fight in the trenches in First World War battlefields. A lot of those men never came home again – almost a million men died in what was referred to as ‘The Great War’. There is a memorial to the men of Burwash who sacrificed their lives fighting for their country, and among the 135 names inscribed there is that of Lieutenant John Kipling of the 2nd Battalion Irish Guards, who died, aged 18 years, on 29th September 1915.

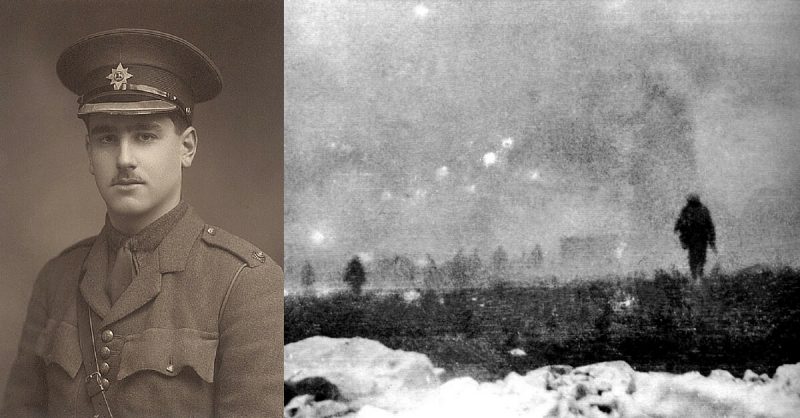

John was Rudyard Kipling’s son, born in Sussex in 1897. When the war was declared, in 1914, John was keen to play his part, and first applied to join the Royal Navy. He was rejected because of his poor eyesight, so he used his famous father’s name to secure a place as a commissioned officer in the Irish Guards.

John Kipling celebrated his 18th birthday in August 1914 and arrived in France the same day. A short period of training followed after which he was sent to take part in what has become known as the Battle of Loos, on the Western Front. The battle is notorious for the huge losses suffered by the British army.

In the first four hours of the battle, 8,000 men were killed, and by the end, British losses totalled 59,247. It was a disaster, and John Kipling was among the dead. The exact circumstances of his death were not known at the time.

John’s body was never found, despite vigorous efforts by his father to get at the facts. Rudyard Kipling was embittered by the loss of his son, and he never stopped trying to discover where his remains lay. He died, aged 70, in January 1936.

In 1992, the Commonwealth War Graves Commission suddenly changed the name on an unknown soldier’s headstone to ‘John Kipling’, sparking a wave of interest.

In 2002, research by military historians Tonie and Valmai Holt suggested that this grave may be that of another officer, Arthur Jacob of the London Irish Rifles.

Meticulous research has revealed that the remains in the grave can be none other than those of Kipling’s son. John Kipling finally had a memorial of his own, almost 80 years after his death. There were three issues that needed to be solved before the unknown soldier could be identified as Kipling’s son:

- There was another lieutenant that had gone missing at the same time, it was later learned he was taken to hospital

- The body was recovered a few miles from where John Kipling was fighting, this turned to be a clerical error.

- The recovered body had the rank of first lieutenant while John was officially a second lieutenant, this too proved to be an error as he was shown to be paid a first lieutenant salary.

With these three issues solved, there could be no doubt that the recovered body was in fact John Kipling

“It is one of the great ironies that Kipling should have been the person to select the phrase ‘known unto God’ for all unknown soldiers, and then not know what happened to his own son,” says Phillip Mallett, author of Kipling: A Literary Life to the BBC.

Kipling worked with Winston Churchill to ensure that all gravestones were the same shape and size, regardless of military rank. The long lines of matching gravestones lining war cemeteries are their legacy.