Aside from the classic British-American film in 1957, Bridge on the River Kwai, the struggles prisoners of war endured in Burma and the making of the “death railway” became a “forgotten war” – it got lost in the Western Front’s heroics and the ugly truth about the horrifying gas chambers found in the Nazis’ prison camps.

But the making of the Burma Railway was one horror POWs made to work there would never forget.

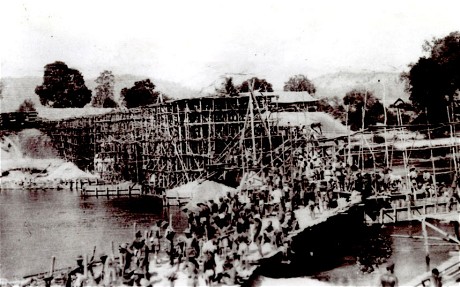

The Making of the Railway

Japan’s Imperial Army devised the construction of the said track to make transport of supplies from Burma to Bangkok easier at the height of World War II. About 180,000 Asian laborers, mostly romusha (forced laborers of the Japanese occupation of Indonesia) and 60,000 Allied POWs captured upon Singapore’s fall in February 1942 were taken into forced labor just so the project would get finished.

The line got finished in a year’s time but at the expense of the lives of around 100,000 laborers and 13,000 POWs. It is said that it cost one man’s life for every sleeper laid.

In the Burmese town of Thanbyuzayat, the end point of the the Burma railway, the “Death Railway”, 3, 149 tombstones of Commonwealth soldiers can bee seen to this day. At the other point, in Kanchanaburi, Thailand, lies the remains of 4, 946 men. All of them died due to the gruesome working conditions they had to go through so that the track could get finished.

But then, the trip home by the POWs from Burma were silent affairs, muted by more bigger news from the West. Each of them were only given £76 as compensation for their ordeals until the Government devised a more humane compensation scheme way back in 2000.

The Unraveling

But today is a different story. It has already been seven decades since the completion of the Burma Railway and a handful of British POWs who lived from the ordeals they experienced there are beginning to go up front and tell their story.

Many of them willingly shared their individual accounts in the hands of their Japanese captors in an interview for a documentary, Moving Half the Mountain, set to be televised this 2014.

One POW’s story, that of late Eric Lomax, is being adapted into film, The Railway Man, with Colin Firth and Nicole Kidman in the lead roles.

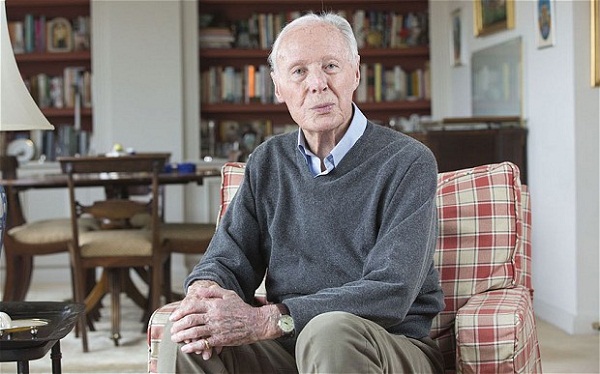

Among the last survivors from the Burma Railway is 95-year-old Sir Harold Atcherley who finally, after seven decades, published his own diary, the one he kept throughout the years he was imprisoned. He endured three years as a POW in Burma, writing down the daily life in the camp he was in by pencil on scraps of paper.

Throughout those seventy years, he had never spoken freely about his war experiences to anyone aside from his own family.

“There are certain things I know that I have never talked about and never would. It was only a few years ago that my son suggested it would be a good idea to publish it,” he explained in an interview with The Telegraph.

His Story

From the moment he was given orders to defend Essex when it was hit by an invasion scare in 1940, Sir Atcherley found the Army disorganized.

“It was a juvenile Dad’s Army. There were 120 of us guarding seven miles of coastline, with one Bren [machine] gun, our 1917 rifles and vests that felt as though they’d been run up by a rope-maker. There were no Army greatcoats so we were given London Passenger Transport Board drivers’ coats,” he recalled.

He was very unprepared for Singapore. After all, he really was an intelligence officer belonging to the 18th Infantry Division and was due to go to Iran for desert warfare training in January 1942 that would then bring him to the battlefields of the Middle East.

However, at the last moment his division was asked to aid the defense of the British colony (Singapore) from the invading Japanese forces.

The Allies numbered over 85,ooo, a greater count compared to the Japanese soldiers who were just around 30,000 but the latter was better prepared than the former.

“The Japanese were constantly outflanking us and used bicycles [to get around the island nimbly] wherever they could. Of our whole Army, only 800 people actually had any training in jungle warfare,” Sir Harold recounted.

The Allied forces were then forced to surrender in the middle of February, leaving then British Prime Minister Winston Churchill “smarting at the worst disaster and largest capitulation in British history”.

The Japanese were also surprised at the Allies’ surrender and were unprepared that soon, they ran out of supplies for their freshly-captured POWs. Sir Harold, along with his division, were later sent to a prison camp in Changi, located east of the island, and were forced to hunt for their own food.

Furthermore, their conditions deteriorated more when they were taken to Thailand in March 1943 to start working on Burma Railway. Originally, they were told by their captors to pack up as they were going to a “rest camp”.

“They told us we should take one-third sick and that it would be much easier to feed us there. That was the last time we ever believed anything they said to us,” he said.

Sir Atcherley’s entries in his diary mapped out their arduous trip to Ban Pong, Thailand through train.

“Five days and nights, allowed to get out of train for 30 minutes a day. No latrine arrangements; we had to urinate out of the wagon door, being held by others as we did so. Little or no sleep at night, very hot by day in all-metal box wagons, too many in each to allow all to lie down at the same time,” he wrote.

They then traveled on foot 200 miles from Ban Pong passing through the jungle into Three Pagodas Pass where they started their railway work.

“Monsoon rains had already started in earnest, 24 hours a day. No roofing on huts where we lived in constant pouring rain.”

They were made to work for up to 18 hours in a single day. They hacked a path through the jungle then used the hacked woods to build a double-decker bridge which would allow cars to pass through underneath the train track.

Their Japanese captors only allowed them 250 grams of rice for nourishment with any greens they could get themselves to go with their ration. heavy work and little food took over and in their weakened state, they soon became exposed to tropical ulcers, beriberi, a disease caused by vitamin B deficiency which causes wasting and paralysis; and dengue, fever brought about by mosquitoes.

“Cholera rife and men dying at the rate of 20 per day. Appalling state of tropical ulcers – cases seen myself of legs bared to the bone from ankle to knee. No sleep for the wretched patients, who moan all night long – their only hope for the morning to look forward to a repetition of all the previous day’s agonies. No man deserves such a death,” Sir Atcherley wrote.

They worked on the bridge for only eight months but of the 1,700 men sent to the Three pagodas Pass together with Sir Harold, only 400 remained alive in October. The 400 surviving POWs were then sent back to Changi where half later succumbed to death brought about by diseases as they endured another year building an airfield in the camp.

Sir Harold had no idea of the breakthrough that was to come on August 5, 1945 – a day before America dropped the first atomic bomb in Japan which forced the country to surrender.

“All feel that things cannot go on much longer as they are. Yet there is no sign of anything significant happening to bring about our freedom,” he voiced out in his diary.

Ten days later, after the dropping of the second atomic bomb, Sir Atcherley wrote again in a more positive note:

“The delight and shock of sudden incredible, wonderful news. 3 ½ years to the day and the war appears to be as good as over. It is difficult to believe that in a week or two we might be free.”

He, together with the other surviving POWs in his division, sailed back to Britain and were received by the Mayor of Bootle – he wrote at this point that “they were worth the Mayor of Liverpool”.

He immediately landed a job with Shell which entailed him to travel through the world and from that point did his best to avoid any talks about the war.

“I’ve never been someone who likes looking back,” he said.

Still, throughout the seventy years that passed, the raw emotion he feels when he recalls the time he spent being one of the workers of Burma Railway has not changed, it is still the same as it had been before.

He admitted that when he attended the preview screening for the new Burma Railway documentary set to be released this year (2014), he spent most of the whole time with tears running down his cheeks.

“It brought back the people I knew who didn’t make it. At the back of my mind I have this guilty feeling: I survived, but others didn’t,” he said.

Sir harold Atcherley’s diary while being a POW in Burma, “Prisoner of Japan: A Personal War Diary”, is published by Memoirs Publishing for £14.50.