A single clandestine meeting three-quarters of a century ago ultimately led to the allying of British and U.S. spy agencies – an alliance that persists all the way down to the present day.

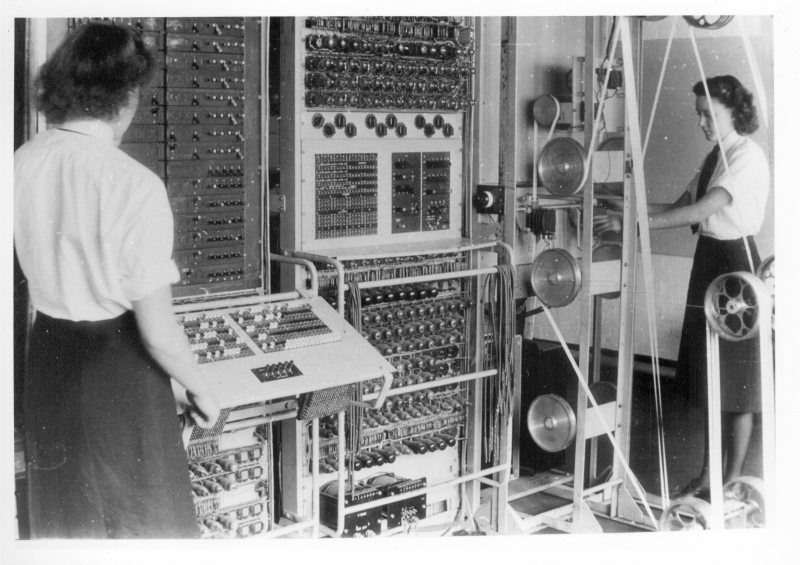

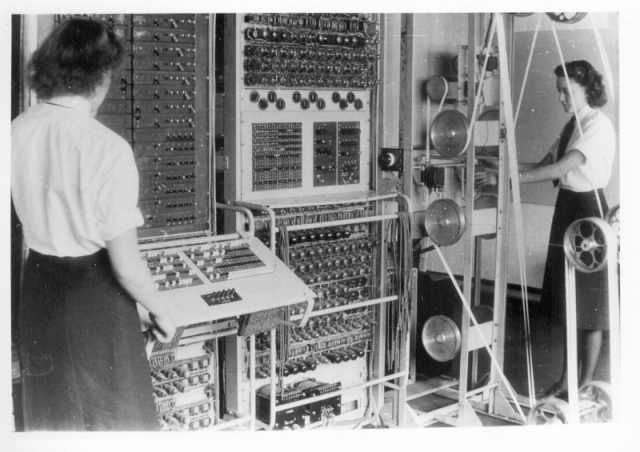

It was before Pearl Harbor, and thus before the official entrance of the United States to World War II. The British agency, housed at Bletchley Park, had thick black-out curtains over the walls, making the already gloomy mansion seem even darker than it actually was. Four Americans arrived at the end of a long, stormy, and dangerous secret mission.

When the meeting concluded, a tentative alliance had formed; British and American intelligence services agreed to work together to fight against the Axis powers – Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Imperial Japan. That alliance, though no longer against the same enemies, continues to be in place today. It’s the longest alliance between two such services in world history.

February 8th marks the 75th anniversary of that meeting, and in its honor, the directors of the two agencies that are still working together have met at Bletchley Park, like their predecessors. Today, heads of the intelligence agencies are Admiral Mike Rogers of the U.S. NSA, and Robert Hannigan, chief of the GCHG. The two men walked up the same path that the four Americans who first visited the facility walked when they arrived for that historic meeting in 1941.

Admiral Rogers was quoted as saying that he believes that the conversations that were had and the agreements that were reached during that one meeting in 1941 directly underpinned the formation of the world’s closest and longest-standing intelligence alliance.

Hannigan agreed, calling the relationship “incredibly close,” and referring to the agreements of that one evening as “a leap of trust.”

The American operatives departed from Annapolis in January of 1941. They brought crates of equipment with them – crates so large, in fact, that they wouldn’t fit into the two pontoon planes dispatched to pick them up in Scotland. Instead, they hitched a ride on an old Navy cruiser down the coast to Bletchley Park.

But they were far from being safe. A German recon plane spotted the cruiser containing the Americans. Dive-bombing and strafing runs ensued that nearly sank the ship. If the Germans had not been using copper-jacketed explosive ammunition, which was unable to penetrate the sturdy crates of equipment the Americans brought with them, the meeting would have been fruitless.

What the Americans had in their crate was their most important code-breaking success in recent history. The United States had replicated a Japanese code machine, for which they’d cracked the code. They intended to give it to the British as a gesture of good faith.

Franklin Roosevelt, then the President of the United States, understood that Britain made an excellent potential ally should the United States enter World War II, as it did some ten months later after Pearl Harbor. The two intelligence agencies were allies in the war effort before the US and Britain were officially allies.

Things were tense at the meeting in 1941 – Britain did not yet consider the U.S. an ally – but the gift of the code machine helped England eventually crack Germany’s Enigma code machine, and served as the basis for the longest spy friendship in world history. One which helped to win WW II and the Cold War and is now essential to the ‘War on Terror’.