The Battles of Narvik refer to the naval offensives and land battle that occurred between the Germans and Allies in Norway. It was one of the first large-scale missions of World War II and initially looked to be an Allied victory, until things took a turn in Europe, leading to an unexpected withdrawal.

A shared interest between the Axis and Allied powers

Narvik, Norway, was of interest to both the Allied and Axis powers. Located in the North Atlantic, its ice-free harbor allowed for the easy transport of iron ore shipped from Sweden. Both sides were interested in securing this supply, and they were willing to breach Norway’s neutrality to obtain it.

The resulting combat would be the biggest battle to occur since the German invasion of Poland in 1939.

Operation Weserübung

On March 1, 1940, the Führer ordered the German invasion of Norway, codenamed Operation Weserübung.

The Kriegsmarine was tasked with occupying six ports, and, a month later, 10 destroyers – Z22 Anton Schmitt, Z21 Wilhelm Heidkamp, Z2 Georg Thiele, Z19 Hermann Künne, Z18 Hans Lüdermann, Z9 Wolfgang Zenker, Z12 Erich Giese, Z13 Erich Koellner, Z17 Diether von Roeder and Z11 Bernd von Arnim – departed.

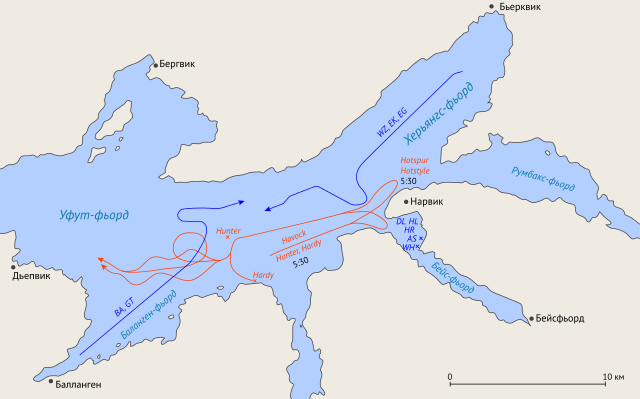

The vessels arrived at the Ofotfjorden leading to Narvik on April 9, where they captured three patrol boats. They then split up. Wolfgang Zenker, Hermann Künne and Erich Knoellner transited to Herjangsfjord, to capture the regimental supply base in Elvegårdsmoen, while Diether von Roeder patroled the water.

Unknown to the Germans, one of the captured ships had sent a message to the Norwegian coastal defense. The ships approached, prepared for battle. However, the enemy sailors had been told to make the invasion as peaceful as possible, so they attempted to convince the Norwegians to surrender. When that didn’t work, the naval offensive began, leading to the German fleet sinking the Norwegian ships. The action was heard by the garrison on land, but they were no match for their invaders.

While the Germans had successfully gained control of Narvik, they soon had another issue: fuel. Their destroyers were running low and had access to only one tanker, instead of the intended two. This forced the fleet to remain in Norway.

First Naval Battle of Narvik

The first of two naval battles at Narvik occurred on April 10, 1940.

It was the British Royal Navy’s chance to defeat the Kriegsmarine with its 2nd Destroyer flotilla, which consisted of five H-class destroyers. They launched a surprise attack in the early hours, sinking Anton Schmitt and Wilhelm Heidkamp, heavily damaging Diether von Roeder and causing minor damage to two other vessels. They also fired torpedoes at the merchant ships near shore, sinking two Norwegian, six German and two Swedish vessels.

The British fleet then became involved in engagements with Wolfgang Zenker, Erich Giese, Erich Koellner, Bernd von Armin and Georg Thiele. They lost two destroyers, while a third was damaged. They then made their retreat.

Second Naval Battle of Narvik

The Royal Navy believed it was imperative for morale and strategic purposes to defeat the Germans. They sent nine destroyers, one battleship and various aircraft to Ofotfjord, instigating a second naval battle. In the ensuing engagement, they sunk three German destroyers, while Wolfgang Zenker, Erich Koellner, Bernd von Armin, Hermann Künne and Hans Ludemann, low on fuel and ammunition, were forced to retreat.

However, they couldn’t outrun the British, which sunk Diether von Roeder and Erich Giese and hit Hermann Künne. They also inflicted damage to onshore batteries and installations. The remaining German destroyers made their way to Rombaksfjord and were soon scuttled.

Upon the conclusion of both battles, Narvik remained under German control. This was largely because no Allied forces were available to make landfall. Without a clear objective, the Allies had settled on bombarding the shore.

Battle in the mountains

The naval battles occurred alongside a land offensive, which, from May 5-10, 1940, was the only active theater on land in the war. German mountain troops, Kriegsmarine sailors and paratroopers from the 7th Air Division faced the Poles, British, French and Norwegians, 5,600 to 24,500.

While the Germans were initially successful in their land campaign, they struggled to survive in the mountainous terrain. Even though they successfully beat the unprepared Norwegian troops during the Battle of Gratangen, they abandoned Gratangsbotn and withdrew from Lapphaugen and Gratangsdalen.

Not long after, the British were reinforced by a French expeditionary force, made up of three battalions of Alpine troops and two battalions of the 13th Demi-Brigade of the Foreign Legion. They were deployed to the south and north of the Ofotfjord.

Norwegian troops began traveling south toward Narvik, before changing direction and heading for the town of Bjørnfjell. By the second week of May, they’d advanced against the Germans east of Gratangseidet, the most significant move on the Narvik Front.

Launching an amphibious assault

With France and Britain growing impatient, the decision was made to launch an amphibious assault at midnight on May 12, 1940. Starting with a naval bombardment, they set their sights on Bjerkvik. The French Foreign Legionnaires were the first to arrive on land, supported by five French Hotchkiss H35s.

The plan was for the Polish troops to aid the French from the west and the Norwegians from the north, boxing in the Germans. After taking Evlegårdsmoen and Bjerkvik, they moved to the northeast, where the Germans were withdrawing, and south along Herangsfjord.

While the plan worked in theory, it failed to account for the trouble Allied commanders had working together. Disagreements resulted in a gap, giving the enemy a path through which they could escape. Despite this, the Allies still planned to attack over Rombaksfjord.

The next day, British Lt. Gen. Claude Auchinleck assumed control of the Allied land and air forces. His mission was to ensure the Allied control of Narvik by maintaining a hold on Bodø, along the German route from Trondheim. He redeployed British troops to the town and appointed French Brig. Gen. Antoine Béthouart to command the Polish and French troops as they worked alongside the Norwegian forces.

On May 28, 1940, at 11:40 PM, a naval bombardment commenced. Two French and one Norwegian battalion were moved across Rombaksfjord to Narvik. The French went east along the railway, while the Norwegians moved toward Taraldsvik Mountain. The Poles advanced toward Ankenes and inner Beisfjord.

By 7:00 AM, the German commander evacuated and retired along Beisfjord, marking the first major Allied land victory.

Operation Alphabet

The Allies had managed to push the Germans out of many areas around Narvik, and it was believed Bjørnfjell would be their last stand. However, it soon became apparent they’d be able to re-establish their control.

It was discovered on May 24, 1940, that the British government had made the decision to evacuate troops from Norway. That night, the fleet received its orders and retreated under the cover of night, so as to not raise the suspicions of the Germans.

The Allied retreat was met with disbelief from the Norwegian government, who felt it would have support until the enemy were forced out. It decided its troops would be able to work alone, leading to an attack order on June 5. However, the offensive failed, and the king and government were evacuated to England on June 7.

Operation Juno

In one last naval offensive, the Germans looked to sink as many British warships as possible. On June 7, 1940, the British aircraft carrier HMS Glorious was loaded with eight Hawker Hurricanes and 10 Gloster Gladiators from No. 263 and 46 Squadrons RAF. This was done out of an abundance of caution, as the Allies worried they’d be destroyed during the evacuation.

Glorious began her journey to Scapa Flow in the early hours of June 8. However, she and her escorts were ambushed by German battleships, destroyers and a heavy cruiser. The fleet sank the Allied ships, causing the deaths of 1,500 men.

More from us: Calvin Graham: The 12-Year-Old Sailor Who Received the Bronze Star During the Guadalcanal Campaign

Despite losing the offensive, the British managed to inflict damage to the German vessel. Their two battleships, Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, had to be retired for repairs, allowing the Allies safe passage through the area later that day.