Here we are again with another instalment of the Images of War series from Pen & Sword. This time round we find ourselves in the jungles of Burma at a time when the Allies were desperate to reverse the advance of the Japanese after the disastrous loss of practically the whole country with all the consequences for both India and the on going struggle in China to consider.

The campaign in Burma was as much a war against the elements as it was a fight between nations. Huge numbers of soldiers succumbed to a range of lethal diseases and the very nature of the conditions would consistently reduce fighting units to handfuls of men in very short order. The Japanese had been built up as a kind of invincible army of supermen in the minds of many European planners. They appeared to cope better with the terrain and refused to fight along the kind of conventional lines many of their opponents had learned at staff colleges and the like.

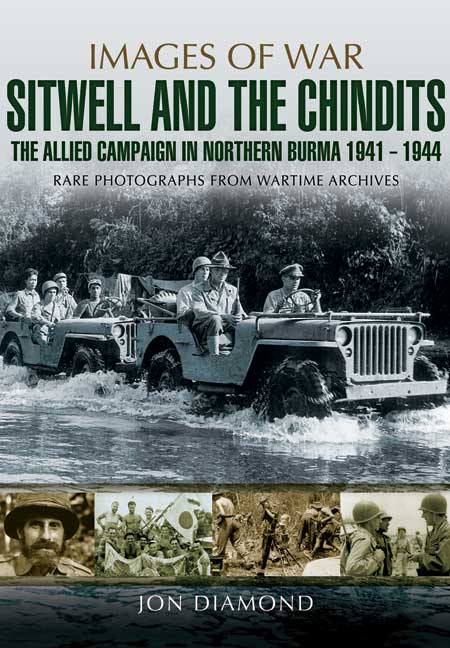

Fortunately some officers were content to be unconventional and found ways to take the war to the Japanese with albeit differing results but the main point was they were on the offensive, interdicting Japanese supply routes and stalling their build ups for attacks on India. The problem was the sheer scale of area the relatively small forces had to fight in. He who defends everything defends nothing and this old maxim dictated that key routes and geographical features became the focus of events. Crossing sometimes wide and fast flowing waterways and just getting through the jungle was an immense challenge. Getting fighting units in was one thing, but getting the wounded out and maintaining supplies was something else altogether.

Aside from practicalities, strategy was another contentious issue for the Allies.

There was a never-ending climate of suspicion surrounding motivation between the British, American and Chinese commanders. It might be fair to say that a piggy in the middle was Joseph Stilwell, a no frills, hardnosed officer who saw his mission as defeating the Japanese regardless of what it took. He was, at times, exasperated with the attitudes and policies of his main allies and wasn’t afraid to show his displeasure.

Stilwell displayed a pronounced Anglophobia in his dealings with the British. He had no times for the trappings of rank some of them expected and showed distaste for his ally’s way of doing things where the traditional position of the officer class and the background of colonial establishment caused him to suspect the British were only interested in regaining imperial real estate rather than totally defeating the Japanese. It’s fair to say thatmilitary and imperial prerogatives were bound to be a problem for the British and cause conflicts in the decision-making. But the military solution – the defeat of the Japanese in detail was the recognised necessity.

To this end, the rise of the truly great Bill Slim, seen by many as Britain’s greatest general of World War II, was enhanced by brilliant victories on the Indian side of the border at Kohima and Imphal in 1944. These successes put the Japanese on the back foot onand ended any chance of a full invasion. Slim may well have been an unvarnished soldier’s soldier prepared to carry a rifle and get out and push when the going got tough, but the singular character of ‘Vinegar Joe’ Stilwell had difficulty dealing with him and indeed any of the British commanders, including the eccentric Orde Wingate whose Chindit operations were giving the Japanese a severe headache, albeit at considerable cost. Wingate did not live to see final victory having been killed in an air crash. He is one of a small number of Brits buried at Arlington National Cemetery. In cooperating with Stilwell, the legendary Mike Calvert faired no better and it got worse when Stilwell took direct command of Chindit brigades operating in northern Burma and drove them to the point of destruction.

Part of wider American strategy was to see the Chinese take a much bigger place on the international stage acting as a counter to the colonial powers and fulfilling the true potential of a vast country with massive human resources. History tells us this plan backfired when the Nationalist regime lost the bitter civil war against Mao’s communists in 1949. But at the height of World War II it isn’t difficult to see why the Americans promoted Chinese advancement. Part of Stilwell’s job was to build up the Chinese army where despite successes the nature of Chinese politics and society in general always worked against him.

The Kuomintang were riven by factions,and with one eye on the advance of the communists, Nationalist unity was severely stretched in the face of any serious plan to defeat the Japanese. Ordinary Chinese citizens were often ambivalent to war aims and many recruits were apathetic and simply voted with their feet. But Stilwell and his American instructors somehow managed to build a force that would prove capable of success against the Japanese.

The Americans committed millions of dollars of supplies to the Chinese and huge amounts of this were stolen by an array of individuals, either for personal enrichment or for stockpiling to use against the communists. The vast American logistical effort with road building and air routes was a stunning achievement in it’s own right, but despite progress on the battlefield Stilwell gradually began to realise his Chinese allies would never fully deliver their end of the bargain and he became disillusioned.

Stilwell may not have got on famously with many of his allies but it is fair to say his methods did not sit so well with many of his compatriots. A member of Merriill’s Marauders is quoted as having the temptation to shoot him when an opportunity arose. Stilwell drove his units hard and had little sympathy for their suffering under intensely tough conditions where men succumbed to exhaustion, disease and malnutrition. Nonetheless his Chinese/American force captured the strategically vital Myitkyina while the Chindits drove themselves to the point of ruin harrying the Japanese.

This book shows these events in a succession of excellent archive photographs.

We see the full range of the story unfolded with images of personnel from all the nations involved in the fighting; Americans, Brits, Burmese, Chinese, Gurkhas, Japanese – they are all here. This is a solid piece of work and I have learned much from Jon Diamond’s well-paced and efficient text. This is definitely one from this series to add to your list. Despite the odd dip, they seem to improve all the time and while they are always dependent on the quality of photographic sources, they work very well in the main. I think of them as being a bit like an extended version of the part-works prevalent in the seventies and early eighties and we generally get a lot of bang for our buck. Full marks.

STILWELL AND THE CHINDITS

The Allied Campaign in Northern Burma 1943-44

By Jon Diamond

Pen & Sword Military

ISBN: 978-1-78383-198-2