The diary of a Nottinghamshire Territorial Army Nurse, Beatrice Hopkinson, who served in the UK and then on the Western Front. Editor Vivien Newman has included a chapter about nursing for historical reference, illustrations, appendices and an index.

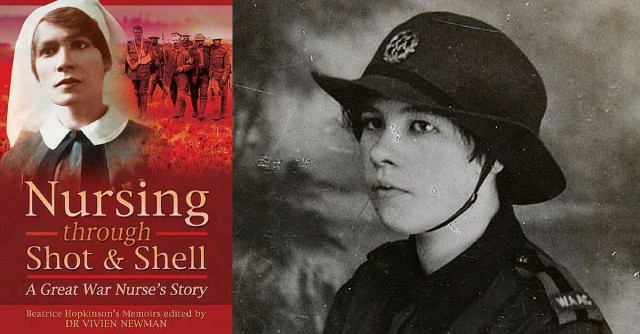

Beatrice had trained as a civilian nurse in Nottingham, and when the war began, she was working as a probationer at the County Hospital, Lincoln. During her time there she worked on the military wards and saw many casualties coming into the system. Her own brother Charles was killed in action serving with the 181st Tunnelling Company, Royal Engineers while she was at Lincoln. Her probation time came to an end in 1916, and it was at this point that she joined up and became a Territorial Nursing Sister. Beatrice was assigned to another hospital in Lincoln specialising in military cases, and she was sent to the Western Front in 1917.

The diary begins in a very idealistic, ‘for God and Country’, sort of way. Beatrice does initially appear to be innocent, and I thought it is amusing that at St. Omer while working at the 59th General Hospital and with the war so very close at hand, she recorded that she was afraid of the bats that flew around the accommodation at night. She soon discovered that there was another serious aerial threat more terrifying than bats; the air raids. The innocence quickly evaporated when the casualties started coming in from the battlefield.

Even though she had seen plenty of casualties and seen some of them die on the wards in Britain, these casualties, fresh from the fighting were different. The book becomes increasingly grim as the war progresses. The casualties continued to roll in; the shelling and the air raids carried on, and Beatrice very quickly became a veteran. In early 1918 she was selected to be part of a six-person team, which would work together at all times and sent to serve in a Casualty Clearing Station very near to the front line. Nurses had to be very skilled, fit and level headed to be assigned to one of these teams. The editor, Newman, is quite correct when she says that most Great War historians know little or nothing about these teams, I for one have never heard of them until I read this book.

The ‘set piece’ in the book for me is the German Spring Offensive. The troops stream by her CCS as do the civilian refugees. Beatrice’s descriptions of the clogged roads and the panicking refugees are graphic and remind me a little of the headlong flight of people described in H. G. Wells’ ‘War of The Worlds’. Beatrice wrote that the guns were firing all of the time and artillery units set up where they could. Sometimes they dug in alongside the medical stations and as they fired they drew fire into the surrounding area. She captures the chaos and fear of these days and the growing realisation among the troops and the non-combatants that the Allies could actually lose the war.

The Allied retreat was attacked from the air, and she recorded how one night a German aircraft strafed her CCS. Beatrice was outside when the Raider arrived overhead, and she firmly believed that the crew used her white headdress as a marker when they opened fire. It is interesting to note that the aircraft was forced down behind Allied lines, and the German crewmen were found to be drunk. There seemed to be no outrage that a medical facility had been attacked. In 1918, after years of total war, such events were commonplace. In fact, anti-aircraft fire and aerial attacks feature quite prominently in the diary.

Cut off from her own unit Beatrice served at another CCS and she recorded that they worked under fire, setting up the hospital tents, treating the wounded and then they retreated once more. There was no sleep and all of the time she was anxious to get back to her unit. Even as a reader I was relieved when Beatrice made it to Boulogne saying, “I shall never forget how utterly hopeless I felt…” At this point, both diarist and reader needed a break.

However, there was no respite. Moving on to St. Omer she re-joined her own unit and was sent straight back into action handling the wounded who streamed in. Needless to say, the retreat ceased and after a pause the movement was all the other way, and the work was just as intense, exhausting and stressful. In a very quiet, private and understated way, while all of the war raged around her, she met her future husband, a young American doctor serving with the British RAMC. After the Armistice, there were still casualties to deal with because 11/11/18 did not spell the end of the suffering. Soldiers and civilians were still in the wards with all manner of physical and mental injuries and the booby traps in the trenches and no-man’s-land, accidents with munitions and Influenza still gave the medical teams plenty of work.

I could go on and tell her story in precis, but I can’t do it justice. So many episodes stand out that it is best to recommend that if you are interested to go and find the book for yourself and have a read. I am often on the lookout for something different in the way of Great War books in the vast array of works that have recently emerged, and this one fits the bill. The book has all of the familiar elements of a Great War memoir or diary but this one stands out because it is by a woman who was on the Western Front. You don’t tour the trenches much in this one, but you live with our diarist just behind the lines trying to patch up the wounded while under fire. For instance, you watch in horror as a wounded, lice-ridden, soldier dies, literally bitten to death by the ‘chats.’ It makes for very different reading; it makes for relentless and sometimes, uncomfortable reading. This is a very good and informative book; innocent, wholesome and whimsical it is not, the grim reality of the Great War it is.

Reviewed by Dr Wayne Osborne for War History Online.

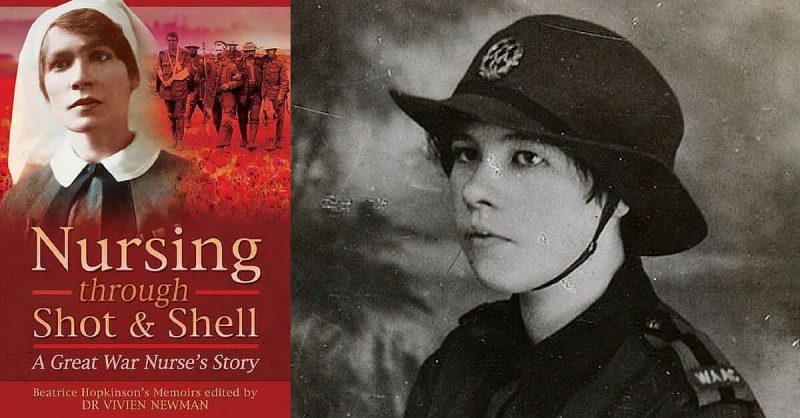

NURSING THROUGH SHOT & SHELL

A Great War Nurse’s Diary.

By Beatrice Hopkinson. Edited by Dr Vivien Newman.

Pen & Sword

ISBN: 978 1 47382 759 2