It’s occurred to me over the last few months that diary keeping was frowned upon and against regulations during a large part of the Great War, and the editor of this work remarks upon this in his introduction. Well, considering the number of personal diaries that keep appearing almost weekly, this output from the war must represent the largest mass incidence of disobeying orders in the histories of the Royal Navy and the British Army bar none.

This diary/memoir edited by David Venner is, on the face of it, the standard fare of a Western Front infantry diary. However, this is a diary kept by a despatch rider, a diary kept by someone who had carte blanche to roam and who had the capability of recording what he saw on his daily rounds. In this diary we are not fixed to the routine of trenches, fatigues, support and rest but can travel from the front to the rear, visiting HQs and other establishments on the way. It is therefore slightly removed and gives us a view of the war from a slightly different angle and like many diaries that are currently emerging this one was worked on after the war’s end.

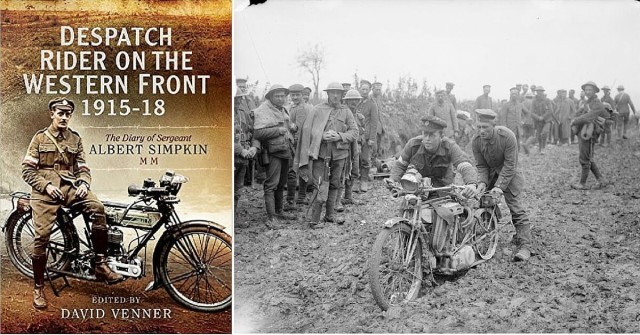

Albert Simkin was an apprentice engineer with the marine engine manufacturers Crossley Brothers of Manchester and as such he could have been employed in a number of roles during the war. Considering the need for skilled engineers on the Home Front I’m surprised that he was allowed to leave the company. However, Simkin was a motorcycle owner and enthusiast which prompted him to enlist as a despatch rider and the army welcomed him with open arms. He joined the 37th Division and went out to the Western Front in July 1915 after completing his training and he remained with the division for the duration of the war. The despatch riders bear a similarity to the pilots of the Great War; in fact a number of riders did transfer to the RFC/RAF during the course of the war. Some drank and some rode recklessly and many paid for it with their lives, with accidents claiming lives almost as often as the enemy did. There is of course a ‘man and machine’ connection here, the bikes gave the riders freedom in the same way that the aircraft gave the pilots freedom and they were both just as dangerous in unskilled or unlucky hands.

Along with the familiar sights of the war there are plenty of ‘road’ descriptions. Lines of communication clogged with traffic, dead animals and refugees. The roads were bombed and strafed, convoys toiled on the ruined roads and the weather was a constant companion to the riders struggling to deliver their messages. So too was distance, the riders could cover a hundred miles trying to deliver a single message, no mean feat considering the bikes that they rode and the conditions that they met. Unromantically but accurately, the despatch riders, in Simkin’s words, were the postmen of the war.

This is a book with a social conscience. Simkin was aware of belonging to a Citizen Army, had a dislike of privilege and was aware of the social differences between officers and men. Although, how much this was a post war construct is unclear. He certainly came into contact with staff officers on a regular basis and he was unimpressed by many of them. His comment, “The Corps General will not use our division as a unit because of our general’s ancestry…” made me laugh out loud. Tragically there were generals like that and such men do the rehabilitation of the Great War generals’ cause no favours at all. (Witness Hamilton mistrusting a division at Gallipoli because a large number of its officers came from Lancashire mill towns, where, in his opinion, no gentlemen could be found.) I think that it is very probable that Simkin’s experience of the war from his position as a despatch rider formed his political and social views. Throughout the diary he gives us his opinions about the battles of the Great War and again I wonder how much of his tactical and strategic insight came from the post war years.

The diary is divided into ten chapters and contains a short index, an itinerary for the 37th Division during the war and a short list of abbreviations. This is a book for bikers, for Great War researchers and enthusiasts. It is witty and grim, sometimes depressed and sometimes cheerful. I enjoyed this book but when one considers that 45,000 words of the original were omitted from the text one wonders what has fallen on the cutting room floor. Sadly, like so many of the Great War diaries/memoirs that are being published at the moment, as the war comes to an end so does the book. The editor obviously had to cut the book down to size for publication (the original is available to view at the Imperial War Museum) but I would have liked to have read more of Simkin’s words and learned more about a Despatch Rider on the Western Front. Nonetheless, it is worth seeking out and reading and if you are a fan of Great War motorbikes and vehicles this is a must.

Reviewed by Wayne Osborne for War History Online.

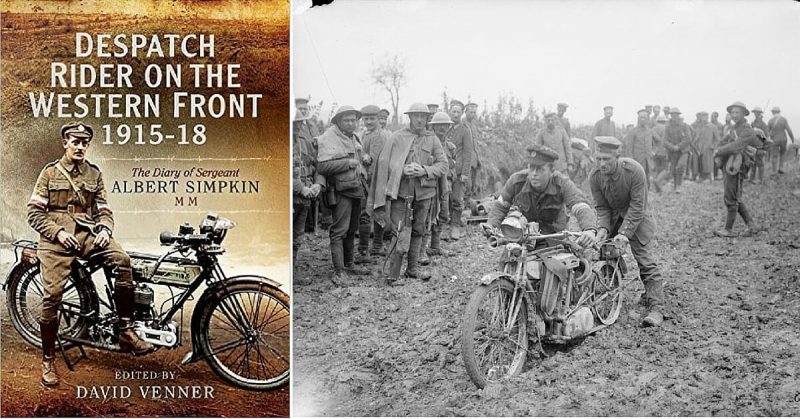

DESPATCH RIDER ON THE WESTERN FRONT 1915 – 18.

The Diary of Sergeant Albert Simkin MM.

By Albert Simpkin MM – Edited by David Venner

Pen & Sword

ISBN: 978 1 47382 740 0

Dr Wayne Osborne is a respected Great War historian who specialises in and writes about British Great War manufacturing and the workforce, Gallipoli, the 17th (Northern) Division and the 10th Battalion, the Notts & Derbys.