I reviewed the last collection of essays edited by Spencer Jones over a year ago and it remains one of the most impressive reads I have enjoyed in a long time. The gathering of a diverse group of respected historians to present key elements of the conflict was a winner from first to last. It was a book outside my comfort zone challenging me to broaden my perspectives. In essence it makes readers like me grow up a little and this is no bad thing.

This second volume is broadly similar but whereas the first concentrated on leadership during the first months of the war this one looks at the difficulties facing the British Army on the Western Front in 1915, a year of heartbreak and much disappointment.

It was a year when the rapidly expanding British Army was faced with fighting battles in support of the French. Britain was junior partner in a coalition where the senior partner had shouldered a greater part of the burden of pushing the Germans back but it had cost France dear and her army was showing signs of flagging under the strain. Despite having a great empire Britain’s regular army was tiny in comparison to the large forces fielded by her European neighbours and the race to catch up proved fraught with difficulty.

The regular army was decimated in the cauldron of fighting from August 1914 onwards and although the remnants had held on and dug in it would be the tens of thousands of volunteers who would take the war forward. The call to arms had been immensely successful, but the demand on British industry to supply the army with ever increasing amounts of shot and shell would lead to recriminations and a full blown scandal in the face of inadequacies in practically every area of procurement.

It was the unhappy combination of the need to conduct offensives it did not choose to fight while lacking the weapons it needed to succeed that would see ever increasing numbers of casualties giving rise to the myth of lions and donkeys on the Western Front.

The Germans were keenly aware of the frailties of their enemies evinced by the month long Second Battle of Ypres when they failed to inflict a decisive defeat on the ‘English’ despite being superior in practically every sense. German industry had the capacity to feed the army’s need for munitions while the country’s scientists were busy developing new weapons that continue to define the war in popular memory. The battle is best remembered for the first large scale use of chlorine gas but the Germans failed to exploit the initial impact of the dreadful weapon giving British and Canadian troops time to recover before going on the counter offensive to shore up the shrunken salient around Ypres.

As important as Second Ypres is to the story of 1915, it is the British offensives on the Western Front during that bloody year that illustrate the urgent need for the introduction of new ideas and tactics in conjunction with better weapons in adequate numbers.

It was an artilleryman’s war and bigger more powerful guns were needed to break down German defences. The British simply did not have enough of them and it would be the infantry who would suffer the consequences in numbers exacerbated by a paucity of understanding of how to fight a new kind of war.

Successful aspects of Neuve Chapelle inspired misplaced confidence but pride always comes before a fall. Aubers Ridge, Festubert and, above all, Loos, were battles fought to fit in with aims the French devised but could not meet. Lord Kitchener, himself; recognised the consequences of the Hobson’s Choice presented to Field Marshal John French by Joseph Joffre but he insisted it was necessary for the BEF to shoulder its share of the burden for the sake of the alliance. The year would see the last vestige of the old army disappear. Thousands of men would die for very little gain as the New Army took up the strain. The disappointments of 1915 would be followed by the cruel reality of a war of attrition in 1916. The high point of late summer 1918 when the British had refined the concept of all arms tactics and had war winning weapons in their arsenal were light years away. Visit the cemeteries of Flanders, the Gohelle and the Artois and the cost of British failure in 1915 is painfully evident.

But there were bright spots. For all the criticism he has faced since his death; Douglas Haig was the coming man who welcomed new weapons and tactical innovation. His belief that victory was just around the corner if the breakthrough could be achieved was barely dimmed by the disappointments of the year. Haig’s ability to work alongside Britain’s ally was just one aspect that made him an attractive alternative to the faltering and mercurial John French. 1915 was the year when understanding the reality of modern war was the only subject on the minds of Britain’s strategists, but disseminating painful lessons would take time.

This book seeks to look at all the elements that made the year so important to the eventual outcome three years hence. It was a year of trial and error on the Western Front overshadowed by the disastrous sideshow of Gallipoli and the calamity of the first day of the Somme a year later. We have only to look at the schedule of centennial commemorations to see a preoccupation with the imagery of futility espoused by a handful of poets that still dominates establishment thinking in Britain. They ignore crucial events and decisions to remain aligned to populist notions of doomed youth current fifty years ago. There was so much more to the war and books like this cut to the chase.

The diversity of voices and the range of subject matter allow the reader to gain a much broader appreciation of events from battalion up to corps level during the key encounters of 1915 in France and Belgium. We see the growth in importance of the Royal Flying Corps and the quest for new solutions to breaking the deadlock of the trenches. The contribution of troops from Canada and India is covered in detail and the fluctuations in the fortunes of the high command say much about the changing face of warfare at the time. The performance of key figures is treated with a sobriety I find most welcome. I sometimes find myself confused with the labels of traditionalism, revisionism and counter-revisionism applied to aspects of Great War historiography. All I want is clarity and it is much in evidence here.

I can’t genuinely describe myself as a student of the Great War in particular. But I read a lot about it and have walked a lot of the battlefields encouraged by the enthusiasm of the late Richard Holmes in print and on TV. I read the works of Lyn Macdonald and her history of 1915 remains a treasured read, but I see all that work as a jumping off point for getting at the heart of the war. 1915 was the year my twenty-year old great uncle Les died at Hooge. He was the impetus for my deeper interest in the conflict and it was men like him who lured me away from Normandy, Arnhem and the bomber war of 1939-45 for quite some time. But variety is my thing and I want to learn as much as I can about a range of military history that sets the scene for the world I live in. This is the sort of book to do just that. It is brilliant.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online.

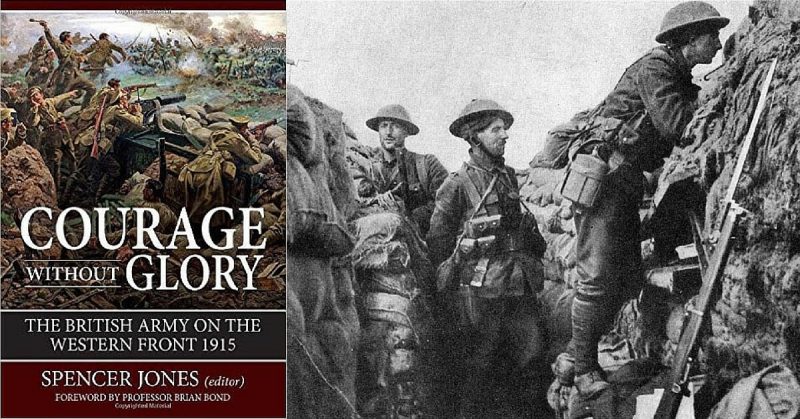

COURAGE WITHOUT GLORY

The British Army on the Western Front 1915

Edited by Spencer Jones

Helion & Company

ISBN: 978 1 910777 18 3