Construction of the IJN Shinano

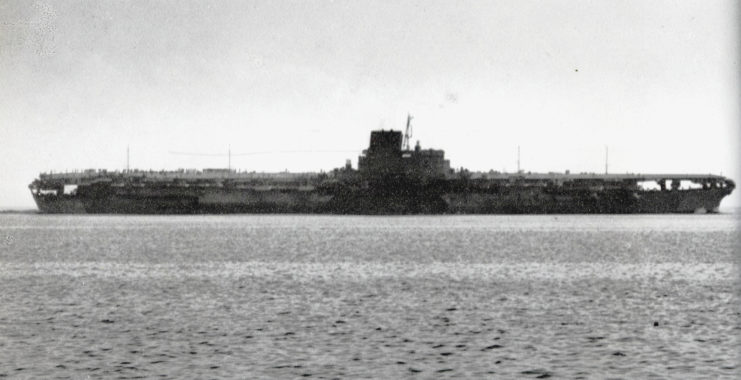

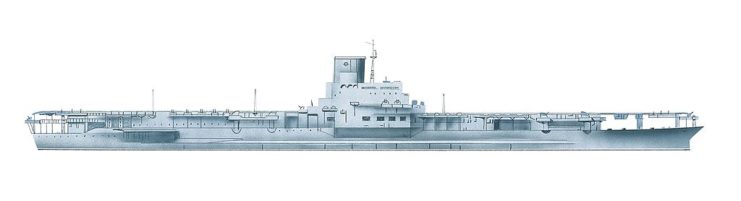

Construction of the IJN Shinano began on May 4, 1940, at the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal and moved forward steadily until 1942. That year, after Japan suffered several defeats against the U.S., military leaders decided to change the ship’s purpose. Instead of finishing it as a battleship, they converted Shinano into a heavily armored aircraft carrier, weighing 65,800 tons. Rather than being used for direct combat, Shinano was meant to serve as a support carrier, carrying reserve planes and fuel for the fleet.

The IJN Shinano was initially based on the design of the Yamato and Musashi, with plans calling for slightly thinner armor and upgraded anti-aircraft capabilities. However, once she was converted from a battleship into an aircraft carrier, her design shifted significantly. Much of her original armor and her massive main guns were sacrificed to accommodate her new role.

Traveling toward certain destruction

Initially planned for commissioning in early 1945, the IJN Shinano‘s construction timeline was accelerated following the Battle of the Philippine Sea. This battle inflicted heavy losses on the Japanese Navy, including the destruction of two fleet carriers, one light carrier, and two oilers, while several smaller vessels sustained damage.

The hastened construction of Shinano led to compromised workmanship on later components. Nevertheless, she was launched on October 8, 1944, and officially commissioned on November 19 of the same year.

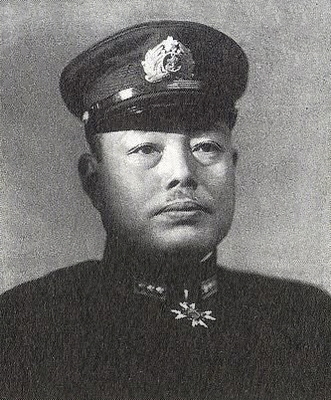

After her commissioning, Shinano was scheduled to travel from the shipyard to Kure Naval Base, where she was to be outfitted with armaments and aircraft under the command of Capt. Toshio Abe. Although Abe requested a delay due to incomplete bailing pumps and fire mains, his superiors denied his appeal and insisted on immediate departure. As a result, he was forced to set sail at night, despite his preference for a daytime departure.

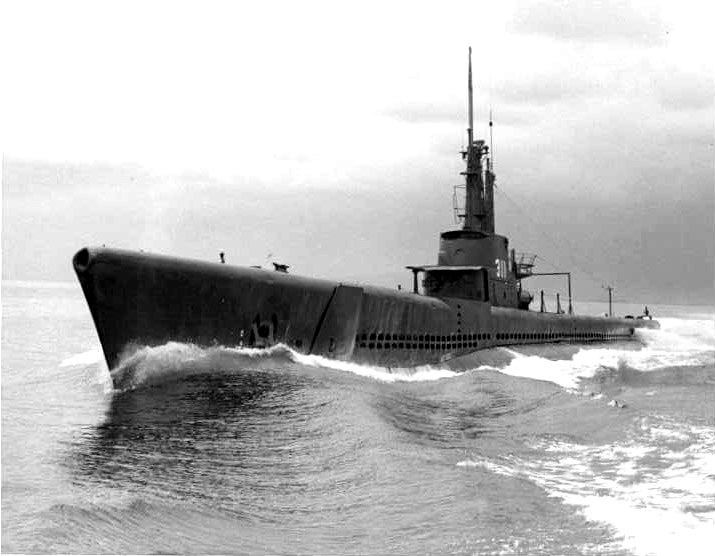

Shinano departed at 6:00 PM on November 28, 1944, escorted by Isokaze, Yukikaze, and Hamakaze. During the voyage, the group detected radar signals indicating the presence of an American submarine nearby, prompting evasive maneuvers. Unknowingly, these actions placed Shinano directly in the path of the USS Archerfish (SS-311).

Sinking of the IJN Shinano

Joseph Enright, the captain of the USS Archerfish, spotted the Japanese aircraft carrier IJN Shinano two hours before the carrier realized a submarine was nearby. Commander Abe, in charge of the Japanese forces, mistakenly thought they were dealing with a group of American submarines and ordered his ships to change course to escape. Even though Shinano was the faster ship, it had to slow down to avoid possible damage.

At 2:56 AM on November 29, Abe first steered his ship toward the submarine but then turned southwest, unintentionally exposing Shinano’s entire side to Archerfish. At 3:15 AM, Enright ordered the launch of six torpedoes. Two of them struck the carrier before the submarine quickly dove to a depth of 400 feet to avoid any counterattack.

In total, Shinano was hit by four torpedoes, leading to her sinking. Enright and his crew didn’t learn the true identity of the carrier until after World War II. They also didn’t know that it took more than seven hours for Shinano to go under after being hit.

Hindsight is 20/20

Initially, those aboard the IJN Shinano underestimated the severity of the damage caused by the torpedo strikes, meaning minimal effort was made to salvage the ship. Abe, in particular, directed her to maintain maximum speed, inadvertently accelerating the flooding of the aircraft carrier.

Unfortunately, by the time they grasped the gravity of the situation, it was too late. The ship had become too heavy to be towed by escort vessels, too inundated to be pumped out and too irreparably damaged for the majority of her crew to evacuate. Out of her 2,400-man crew, 1,435 perished with the ship, including Abe and both navigators.

The survivors were sent to Mitsukejima until January of the subsequent year, preventing the widespread dissemination of news about Shinano‘s sinking. Following the conclusion of the war, the US Navy analyzed the aircraft carrier, along with other Yamato-class ships, and identified significant design flaws that rendered specific joints susceptible to leakage. It was concluded that the torpedoes from the USS Archerfish happened to strike these vulnerable joints, contributing to Shinano‘s demise.

Regarding Enright, US Naval Intelligence initially doubted his claim of sinking a Japanese carrier, believing all had been identified. However, this was rectified after the war, and Enright was duly honored with the Navy Cross for his victorious achievement.