Compared to the inconveniences that plague the average beachgoer – overcast skies, sand flies, or jellyfish, to name a few – the problems faced by the residents of the Falkland Islands over the past four decades is a little bit more alarming than most.

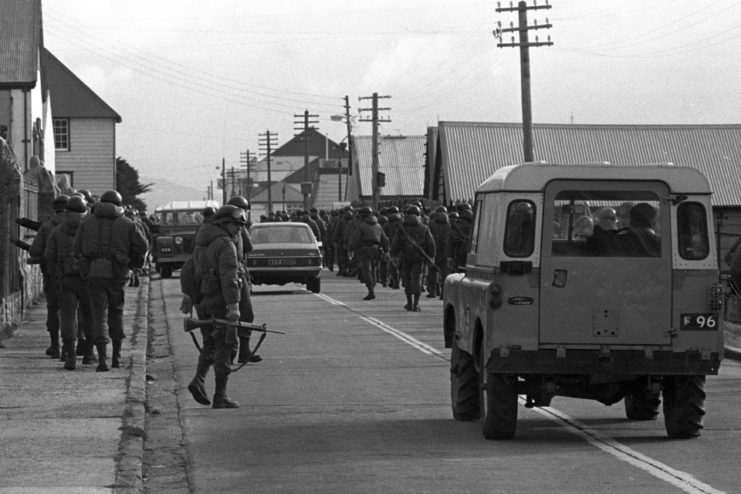

Since 1982, when a territorial dispute saw the British Overseas Territory invaded by Argentine forces, large areas of this group of islands in the south Atlantic have been off-limits to all human usage due to the tens of thousands of landmines left behind by Argentine troops.

Now, thanks to an international effort involving teams of veteran de-miners from Zimbabwe, the Islands have been declared landmine-free. The last beach to be cleared, a north-facing exposure on an archipelago at the eastern tip of the islands, was declared safe this month after a decade-long effort. Remarkably, notes Welsh transplant Dr. Barry Elsby, this feat was carried out without a single fatality or serious injury on the part of the de-mining crews.

The effort was driven in part by the United Kingdom’s commitment to an international anti-personnel mine ban, but its effects go far beyond the realm of political posturing. According to Elsby, some islanders under the age of 40 have never been able to walk on Yorke beach, and the final clearance is a weight off the minds of residents who have lived with the reality of war for decades after the last shot was fired.

Despite the gravity of the daily reminders in the way of warning signs and tourist advisories, he says the Island is a wonderful place to live – having originally planned to stay only two years when he arrived with his wife in 1990, he says the Islands quickly captivated him and he has made them his new home, now involved in the Islands’ government as one of eight members of the legislative assembly.

For some of the de-mining personnel whose expertise brought them overseas from Africa, the Falklands have begun to cast a similar spell. Dressed in NATO-issue body armor and heavy black face shields, the Zimbabweans work with metal detectors and trowels to locate and expose the remaining mines before defusing them.

The mines, a mixture of many nations’ manufacture, are built in two disc-shaped halves connected at the centre that are twisted together to arm and twisted apart to disarm – it is unbelievably dangerous work, but for many of the men, it is a job like any other.

The men have significant experience de-mining the borders of their home country which was heavily mined during its war for independence in the 1970s. Their expertise has found them employ in former battlegrounds throughout the world, but at least one of them intends to remain in the Falklands.

Blessing Kachidza, a survey engineer who came to the Falklands as a de-miner, has secured work with the Falkland Islands Company, a British company chartered in the mid 19th-century that now provides logistics and tourism services on the Islands.

A Zimbabwean church community has sprung up, and a generation of children born to Zimbabweans on the Island looks to change the primarily British demographic of the island as the de-miners take their place in the community they have helped to make safe.

Their migration to the Islands is not without tension, notes de-mining operations manager Phillimon Gonamombe, adding that “one person can spoil our reputation” – but few can argue that the men who risked their lives dismantling ordnance that the even the demure indigenous Gentoo penguins are too light to set off have earned their place.

Wendy Morton, the UK cabinet minister responsible for the Falklands, pays tribute to the de-mining crews and their work, but adds that the mandate of the UK’s de-mining program is never finished:

Another Article From Us: Blood, Metal, And Dust: How Victory Turned Into Defeat in Afghanistan and Iraq – Review

“Our commitment to ridding the world of fatal landmines does not end with our territories being mine-free,” she tells BBC. The government has allocated £36m to continue de-mining efforts wherever they are needed to continue to protect civilians from the remnants of armed conflict the world over.