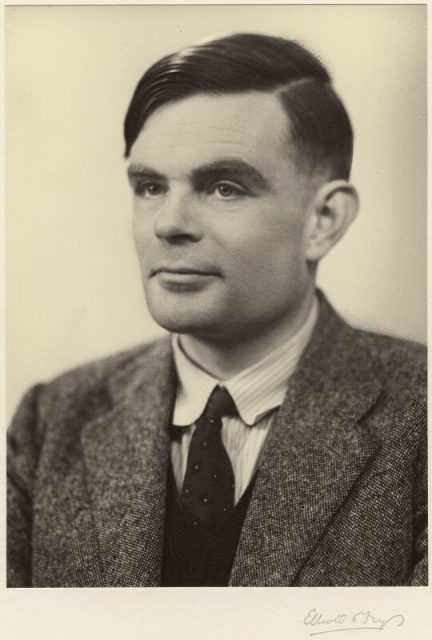

Alan Turing, one of the greatest mathematicians Great Britain has ever produced, is getting another “thank you” of sorts from the British government.

It is all “too little, too late” of course, as the government prosecuted Turing for his sexual orientation in 1952, and he died by his own hand shortly thereafter. But the government’s latest step toward restoring his legacy is putting Turing’s likeness on a new 50-pound note.

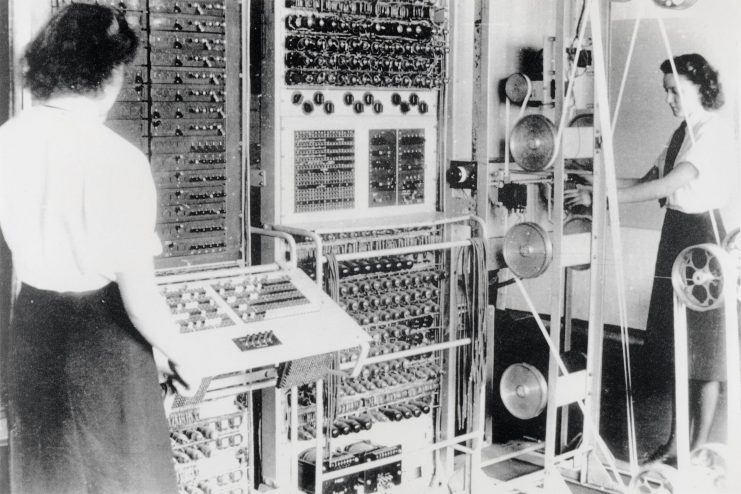

The British government of World War II turned to him to crack Germany’s Enigma, the cipher used by the Nazis to hide the times and locations of attacks by its submarines.

The Enigma machine caused Great Britain massive losses, until Turing and his team broke the code and interpreted its messages for wartime officials while stationed at Bletchley Park.

But once the war ended in 1945, Turing became vulnerable to the same bigotry and unease any other homosexual in Britain faced. In 1952 he was prosecuted for, and found guilty of, “gross indecency” for having a sexual relationship with a man.

Instead of going to prison, he chose pharmaceutical castration, which left him impotent and affected his intellectual prowess.

Rather than continuing like that, Turing took his own life by ingesting cyanide in 1954. Ever since, the British government has been executing an ongoing series of posthumous apologies, so to speak, to make up for the abhorrent treatment Turing received.

Turing’s contributions to the war effort against Nazi Germany are incalculable. It’s unlikely the Allies would have won the war when they did had Turing not been able to “translate” the messages sent to German U-boats in the North Atlantic.

The knowledge enabled the British Navy to prepare and be ready to counter attack, which it did, frequently sinking many German submarines in the process.

By the 1960s, English society’s attitudes toward homosexuality began loosening up, and sexual orientation was tolerated somewhat.

It was finally decriminalized in 1967, and slowly the authorities stopped persecuting people for their sexual orientation. But that was far too late for Alan Turing.

The series of apologies to Turing began with public acknowledgements by officials of his profound contributions to the war effort.

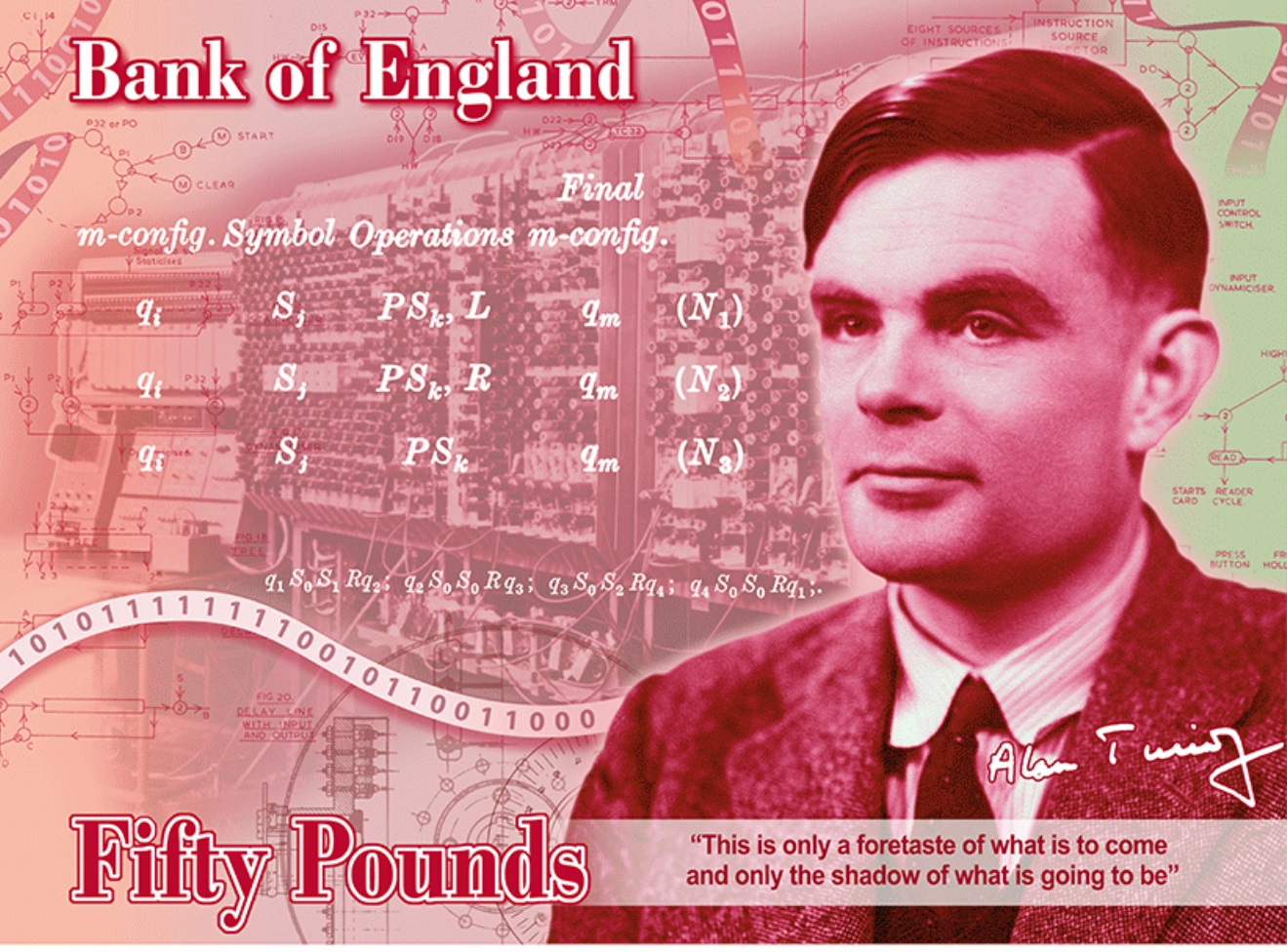

Then came a royal pardon, almost 60 years after his death. Mark Carney, governor of the Bank of England, said in a recent ceremony to announce the new note, “Alan Turing was an outstanding mathematician whose work had an enormous effect on how we live our lives today.

As the father of computer science and artificial intelligence, as well as (a) war hero, Alan Turing’s contributions were far ranging and path breaking. Turing is a giant on whose shoulders so many now stand.”

One British gay activist, Peter Tatchell, concurred. He told The Guardian that Turing’s recognition on the 50-pound note “is a much-deserved accolade for one of the greatest minds of the 20th century.”

The bank held a competition of sorts to gather suggestions on who should grace the new note, which will not be in circulation until 2021. Almost 230,000 names poured in, but only about 1,000 of them met the required criteria.

From there, the list was whittled down to 12, and Carney made the final selection. In the end, Turing was competing with other famous scientists like Stephen Hawking for the honour. Carney said he considered many things before choosing Turing, although some quibbled that he should have chosen someone of colour.

“We want to represent as best as possible all aspects of diversity within the country, from race, religion, creed, sexual orientation, disability and beyond,” Carney said in a statement.

“What we have today (in the choice of Turing) is a celebration of one of the greatest mathematicians and scientists in the United Kingdom, not just in this country’s history, but world history.”

The choice of Turing cannot be argued with in that context, certainly; he helped win a world war. Yet he paid the ultimate price – his life — for simply living honestly as a gay man.

Today, he is celebrated in books and films, like 2014’s The Imitation Game, starring Benedict Cumberbatch as the beleaguered but brilliant scientist in an Oscar-nominated performance. And of course accolades like this, his likeness on the 50 pound note, will keep Turing’s image in front of the British public for decades to come, perhaps even generations.

But it all seems lacking, somehow, considering what Turing gave his country, and indeed the world, compared to what he was ultimately forced to give up.

It is the best the British government can do, unfortunately – pay tribute to a man who in so many respects was responsible for guaranteeing the nation’s freedom.

Another Article From Us: PBY Wreck Found in Irish lake

If only officials had recognized those contributions at the time, and at the very least left Turing alone to live his life in peace. That’s all anyone asks, really, and it is something that surely war heroes, in particular, deserve.