Project Iceworm was a covert Cold War initiative by the U.S. Army to establish a hidden network of nuclear missile launch sites beneath Greenland’s ice sheet. The aim was to position nuclear weapons close to the Soviet Union, using the thick ice as a cover to prevent detection. However, the plan encountered a significant issue—the ice sheet was constantly shifting and changing, which made it impossible to maintain the stability of the underground system over the long term.

To test the concept, the Army constructed Camp Century in 1959. This experimental base featured living quarters, laboratories, and even a nuclear power plant, all buried beneath the ice. But as the glacier continued to shift, the tunnels and structures began to collapse and deteriorate. Within a few years, it became evident that the environment was too unstable for such a project. By 1967, Camp Century was decommissioned, marking the end of Project Iceworm.

Getting permission from Denmark

In 1951, the United States and Denmark signed the Defense of Greenland agreement, which allowed NATO members to discuss the possibility of establishing military bases in Greenland to help safeguard the country and other NATO territories. This agreement effectively gave the U.S. the green light to build a base on the island.

However, the agreement did not grant permission to place nuclear missiles there. When the U.S. Army began planning a facility in Greenland, Danish Prime Minister H.C. Hansen advised against introducing nuclear weapons to avoid stirring international tensions. Despite this, when U.S. Ambassador Val Petersen inquired about the Army’s plans for a base, Hansen did not give a direct refusal, leaving the door open for the project to proceed.

The U.S. Department of Defense presented the project as a means to test construction techniques in Arctic conditions, experiment with portable nuclear reactors, and conduct scientific research on Greenland’s ice cap. However, the key objective of the base—stationing nuclear missiles in the region—was conveniently left out of the official narrative.

Camp Century

The Army named the project “Camp Century,” using it as a public disguise for the true nature of the operation.

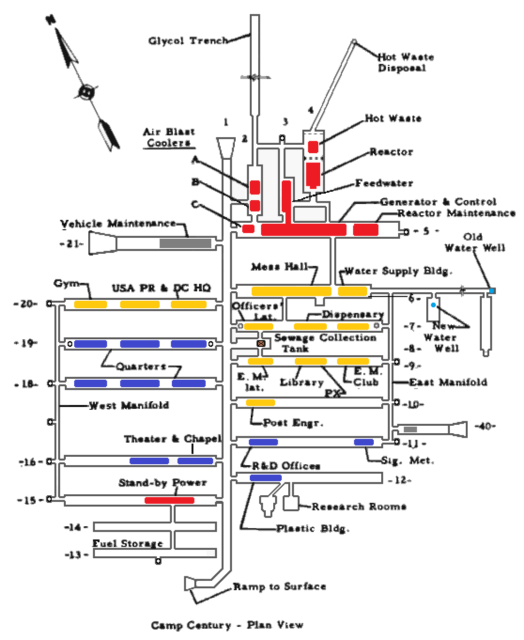

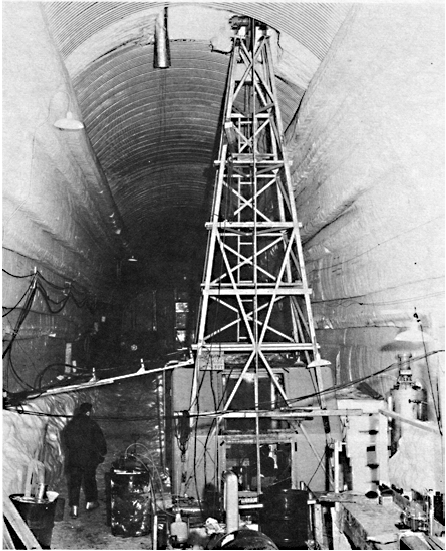

Construction began in June 1959 and was completed just over a year later, in October 1960. The process was challenging. A three-mile-long access road was built to transport equipment and supplies to the location. Trenches were dug into the ice, reinforced with steel arches to create a roof, and then covered with snow for additional protection and concealment.

Within these trenches, wooden buildings were put up, with gaps left between the walls and the ice to minimize melting caused by internal heat. The base was insulated, sourced fresh water from the ice, and was powered by the world’s first portable nuclear reactor (the PM-2A), which was installed in 1960.

Camp Century was capable of housing over 200 soldiers and included various amenities, such as a kitchen, cafeteria, laundry, communications center, hospital, chapel, and even a barbershop. It featured 26 tunnels and acted as a testing ground for assessing the viability of operations beneath the ice.

Project Iceworm

Camp Century was really just a cover story for the Army’s top-secret project called Iceworm. Inspired by Camp Century’s layout, Project Iceworm aimed to build a massive network of underground tunnels stretching over 52,000 square miles—an area about three times the size of Denmark.

Within this huge tunnel system, the U.S. planned to deploy 600 “Iceman” ballistic missiles, each placed four miles apart. The project also included plans for 60 Launch Control Centers to manage the missile network. The goal was to bury these weapons deep under Greenland’s ice sheet, giving the U.S. a hidden advantage for launching strikes—mainly aimed at the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

The Iceman missile was a modified version of the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) and could hit targets up to 3,300 miles away. To keep the whole operation running, the Army expected to house around 11,000 troops at the site.

Problems with Project Iceworm

On paper, Project Iceworm looked like a great plan—placing nuclear missiles close to Soviet targets gave the U.S. a big strategic edge. But problems started showing up not long after the project began.

Within just three years, ice core samples showed that Greenland’s ice cap was shifting much faster than expected. By 1962, the ceiling in the reactor room had already dropped five feet and had to be lifted back up. At that pace, the tunnels and base would be crushed within two years.

After learning this, the U.S. Army decided it was too risky to store hundreds of nuclear missiles in such an unstable environment. On top of that, changing the Iceman missiles to work in the Arctic would have been expensive, and it was hard to figure out how to communicate with missiles buried deep under the snow.

Because of these problems, Project Iceworm was officially shut down in 1963, and no missiles were ever placed in Greenland. That summer, Camp Century was converted into a seasonal base, now powered by diesel after its PM-2A nuclear reactor was shut off. The reactor was taken out the next year, and by 1966, the whole base was abandoned.

Campy Century could have a long-lasting ecological impact

Project Iceworm remained a secret until the Danish Institute of International Affairs began investigating the former military base. Documents about the Army’s true intentions were declassified in 1996, and the secret about Camp Century was finally revealed to the public.

Years after the base was shuttered, its tunnels collapsed, and now a thick layer of ice covers the once-operational facility, making it virtually unreachable. However, the operation wasn’t for nothing, as Camp Century actually provided valuable information via the collection of some of the world’s first ice core samples.

The environmental effects of Project Iceworm may be awaiting society in the future. While Camp Century was in operation, its nuclear reactor produced over 47,000 gallons of radioactive waste that’s still buried under Greenland’s ice cap.

More from us: How Many Times Did the World Nearly End During the Cold War? Answer: A Lot

Scientists believe that, if climate change continues at the rate it currently is, the ice cap could melt enough to expose the nuclear waste by 2100, which could negatively impact the ecosystems within the surrounding area.