How changes at the last hour led to great repercussions

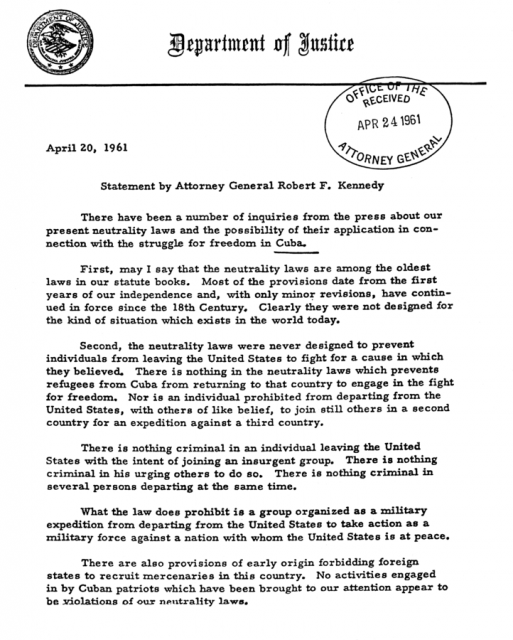

The initial plan for the 2506 Brigade, composed of exiled Cuban freedom fighters, to invade Cuba and overthrow Fidel Castro with American support, was modified by President John F. Kennedy, who was concerned about the impossibility of denying American participation in such a large-scale assault.

In the air, President John F. Kennedy gave an order to cut the number of participating aircraft in half–from 16 to 8. This decision ended up being the deciding factor in loss of control of the air space during the disembarkation of 2506 Brigade.

The plan had three parts: first, American airstrikes would start from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, in order to eliminate the Cuban air force by bombing their planes and airport runways.

Second, Playa Girón was chosen as the landing site for the ground assault. This remote place on the south coast of Cuba, a swamp infested with mosquitoes and crocodiles, has a small airstrip at the mouth of the Bay of Pigs.

(Kennedy was forced to answer difficult questions on Cuba 5 days before the Bay of Pigs Invasion, 12 April 1961 (question starts on 2:55))

The intention was to establish a beachhead. During the disembarkation, supply and protection flights over the attacking forces would continue.

A simultaneous disembarkation was planned near the town of Playa Larga, 35 kilometers at the end of the bay, but was canceled by President Kennedy.

The final stage of the plan was that after three days, the 2506 Brigade would request the transfer of a Provisional Government from Miami to Cuba, and then formally request US military assistance.

The Military Operation

Day 1 – April 15, 1961 – No Air Control

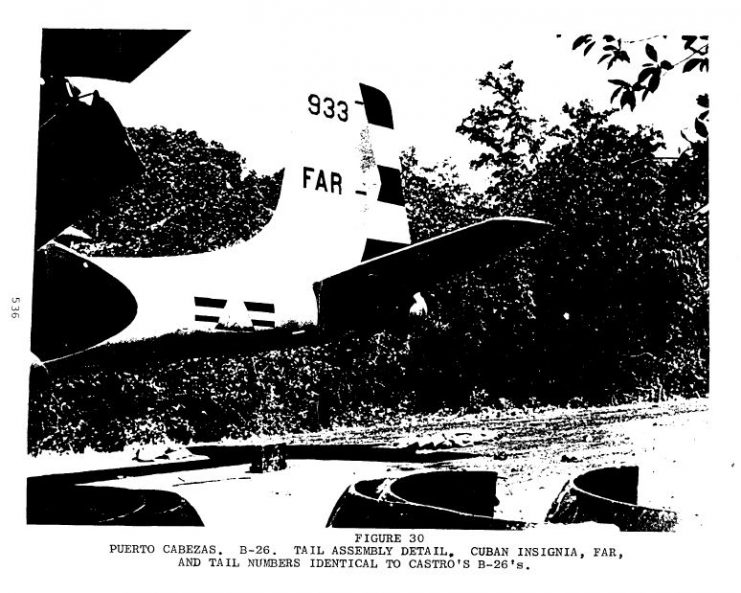

Eight B-26 bombers, with the Cuban flag on the fuselage, bombed the Antonio Maceo airport in Santiago de Cuba and the military airports of Ciudad Libertad and San Antonio de los Baños.

The result of this operation was modest. A Sea Fury, 3 B-26, a C-47 transport aircraft, and a few civilian aircraft were destroyed.

However, although the CIA mistakenly believed the bombing runs had liquidated the Cuban air force, enough T-33, Sea Fury, and B-26 aircraft remained intact to be decisive in the combat on the following days.

This error at the outset practically condemned the whole operation, because the air supremacy remained on the Cuban side.

Since the Second World War, it became clear that dominating the air is vital in all modern conflict.

On the part of the Fuerzas Aereas de Liberación (Air Forces of Liberation/FAL), one B-26 was shot down by the Cuban antiaircraft artillery, another was diverted to Grand Cayman due to low fuel, and a third was damaged, landing at Boca Chica airfield in Naval Air Station Key West, Florida.

As part of the CIA’s cover-up to hide the participation of the United States in the bombing, a B-26, piloted by Captain Mario Zunigas, flew directly from Happy Valley in Nicaragua to Miami. After landing, he identified himself as a deserter of the Cuban Air Force and claimed that he and other pilots had been the perpetrators of the attack on the airports, and that they were part of a military group whose objective was to overthrow the Castro government. This deception was short lived.

2 more bombings were scheduled, even one the day of invasion; however, after the first protests of Cuba to the United Nations and the unconvincing story of the B-26 landing in Miami, President Kennedy ordered the suspension of the bombings on the following days. This turned out to be a major mistake.

Day 2 – April 16, 1961 – Unwanted Effects

The operation consisted of 2 fundamental phases: the military action of establishing a beachhead, and an uprising throughout the entire island.

The bombing on April 15 had contrary consequences. Apart from not achieving air supremacy and making it clear that in a few days there would be an invasion, it triggered another important reaction.

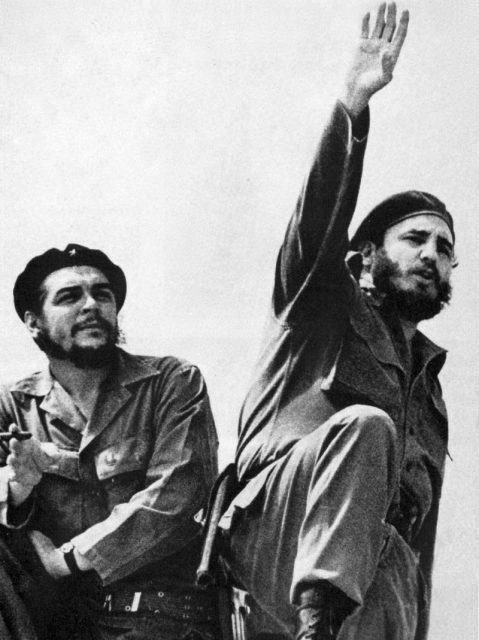

On April 16, Fidel Castro gave a speech in the presence of a huge crowd armed with Belgian and Czech rifles, and declared for the first time the socialist and Marxist character of the Cuban Revolution, despite the fact that in 1959 he had repeatedly rejected Communism in interviews with the press.

Fidel Castro’s speech had a strong impact regarding any possible internal uprising manifestation.

Fidel Castro considered it to be a foreign intervention, and called all the people to defend the Homeland. The Cuban army and the Revolutionary National Militias were concentrated, waiting for a possible invasion.

The State Security Department of the Cuban Revolution (better known as G-2) carried out an extensive raid to imprison a large number of potential opponents, which neutralized numerous contacts between citizens and members of the 2506 brigade, particularly in Havana.

Day 3 – April 17, 1961 – The disembarkation and the losses of the freighter ships Houston and Rio Escondido

On the third day, freighter ships departed from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua, carrying all the arsenal and the Brigade members. This was done with the approval of President John F. Kennedy as a continuation of the previous government’s policy.

At dawn on April 17, about 1,200 members of the 2506 Brigade landed at Playa Girón and Playa Larga, which had some 30 kilometers distant between them, and found little resistance in their advance.

The invading fleet consisted mainly of 4 freighter ships chartered by the CIA: Houston (code name Aguja; Needle), Rio Escondido (code name Ballena; Whale), Caribe (code name Sardina; Sardine), and Atlantico (code name Tiburón; Shark).

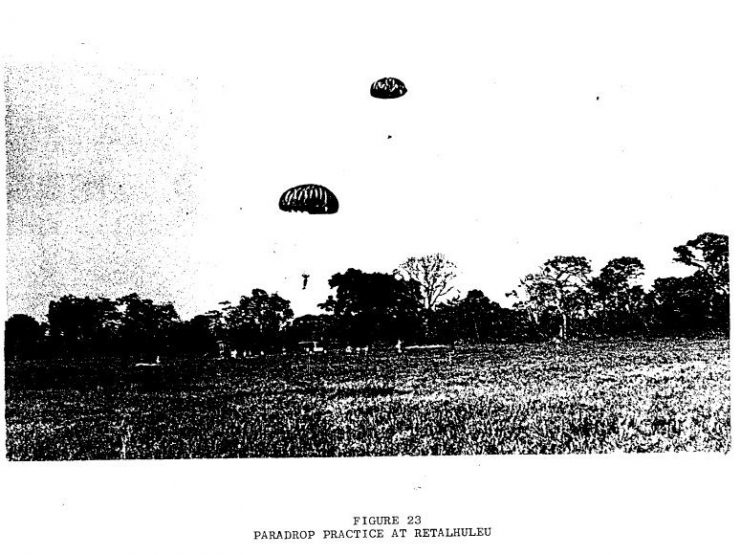

Hours after the disembarkation, paratroopers were transported to Horquitas, Central Covadonga, Central Australia, San Blas and Pálpite, to expand the invaded area and control access to the site.

In those first hours, however, the Cuban air force destroyed several B-26 aircraft. In those B-26’s, the turrets of the rear machine guns had been removed in order to reduce the weight and to increase the autonomy of flight; but this came with a high cost, as it prevented the B-26’s from defending themselves with all their weapons as they normally could have when an enemy was located on their tail.

This situation caused the freighter ships to be left unprotected against the attacks of Cuba’s Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias (Revolutionary Armed Forces/FAR) planes, which put Houston and Río Escondido out of combat near Playa Larga, also losing the supplies they were carrying.

Houston was hit by a rocket launched by a T-33. The captain of the ship ran it aground to prevent it from sinking completely, but that could not prevent part of the men from being drowned or hit by artillery on the deck. Those who reached the shore, tried to reach Playa Larga.

For its part, Rio Escondido was hit completely by enemy bombings, causing a gigantic explosion due to the fact that it contained fuel and ammunition. The loss of this freighter ship was a major setback because it contained medical supplies, food and the radio with which communication was established with the FAL.

In view of these losses, at the end of the day the remaining ships of the assaulting brigade retreated definitively, leaving unloaded equipment and ammunition.

The regular troops of Fidel Castro’s regime were gradually arriving into the area, reinforcing the militiamen (Revolutionary National Militias) who until then had been trying to repel the attack.

In this way the fight gradually changed irreversibly in favor of Castro’s troops.

Day 4 – 18 of April of 1961 – Counteroffensive of the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias

The counter-offensive began with the massive use of artillery acquired from the Soviet Union and Czechoslovakia.

The battered troops of the 2506 Brigade that controlled the two access roads to Playa Girón were forced to retreat to the area of San Blas.

The troops of the brigade in Playa Larga, faced with a difficult situation due to lack of ammunition, decided to abandon their positions and go to Playa Girón to join the other members of the brigade. The Cuban regular army took control of Playa Larga.

Day 5 – April 19, 1961 – The Defeat

The assaulting forces had to retreat from San Blas to Playa Girón; those who remained were soon surrounded, and surrendered in the early hours of the morning. On the beachhead, the shortage of ammunition combined with the lack of air support to hasten 2506 Brigade’s defeat.

The Cuban commander José Ramón Fernández (“Gallego”) and Fidel Castro himself moved to the conflict zone and participated in the last actions.

Fidel Castro pressed hard against the remains of the brigade resistance, forcing them to surrender.

The members of the brigade tried to flee, some looking for boats, others hiding in the swampy areas. Most were captured. Some members of the brigade wandered for days through the dense mangroves of the area.

The operation ended with a total defeat of the members of the 2506 Brigade.

Consequences

The number of casualties among the invaders exceeded a hundred dead; the captured were 1189.

The prisoners were tried and condemned by the Cuban Communist government, then exchanged through intermediaries with the US government in exchange for 53 million dollars in the form of food, medicines, and tractors.

At the end of 1962 they arrived in the United States, where they were received and honored by President Kennedy.

The victory became an enormous factor in the consolidation of Fidel Castro’s regime and the socialist character of the Cuban Revolution.