When thinking of crusaders, the Knights Templar and Hospitaller first come to mind, being the most famous of the Christian warrior Orders. Another Order was just as powerful as them, although its influence was focused in Eastern Europe rather than the Holy Land.

This was the order of the Teutonic Knights.

Beginnings

Founded during the Siege of Acre (1189-1190), the Teutonic Knights were primarily a group of German warriors. Like the Hospitallers of St Thomas of Canterbury, they provided an association bringing together warrior nobles from a single area of Europe. These nobles had gone to the Holy Land in search of fame, glory, wealth, or redemption. They quickly became the foremost group for central European crusaders in the East.

Papal Blessing

By the late 12th century, knightly Orders were officially recognized by the church hierarchy. In 1199, the Teutonic Knights had become quite large and were important enough to receive the Pope’s endorsement.

Limited by Rivals

Although they were a popular group, the Teutonic Knights struggled to establish a power base in the main crusading region of the Holy Land. The Hospitallers and Templars already occupied many of the castles and positions of power available in the area. They saw no need to share them with the newcomers.

Their influence in the Holy Land being restricted, the Teutonic Knights turned their attention back home. Christian Europe was expanding eastward, on the fringes of the Germanic region. This created clashes between Christian settlers and pagan rulers. It was a perfect area for crusaders to fight in.

Joining the Order

On joining the Teutonic Knights, new members took a vow of poverty, chastity, and obedience. This was usual amongst knightly Orders. It reflected a focus on God above worldly matters, and the connection between obedience, authority, and religious duty was common in medieval Christianity.

Avoiding Pride

In theory, members of such an Order were as much like monks as they were knights. Their Christian duty extended to avoid the sin of pride.

This led to walking a delicate line where battlefield equipment was concerned. One of their tasks was to maintain their weapons and armor; usually done with a sense of pride. To counteract this, the bright colors and precious metals used to decorate the equipment of secular knights were banned.

Support Staff

Though the most prominent members of the order were noble knights, they were supported by many other members. Clergy dealt with religious services. Servants carried out chores and maintenance. For every knight, there were ten men-at-arms from the common stock, known as half-brothers or grey-mantles, who provided military support.

Lordly Pursuits

Unusually for a religious Order, the Teutonic Knights were given permission by the Pope to indulge in the sport of hunting. Like other noblemen, this helped them keep in practice for war. They hunted creatures such as wolves, bears, and boars.

Avoiding Women

To maintain their chastity and keep them focused on their holy work, the knights were not allowed to interact with women. This was easy in their home bases, which were occupied only by men. When going out into the world for diplomacy, recruitment, or even war it became more difficult.

As a result, the Knights were banned from attending plays, weddings, and other occasions where there might be drinking and worldly distractions. They were not even allowed to embrace female family members.

Selecting a Leader

The Teutonic Knights were led by their Grand Master. He oversaw the running of the organization and was its main diplomatic face.

Choosing a Grand Master was a complicated process. All available knights in the area were summoned. They elected a series of 13 representatives in succession – eight knights, one priest, and four men from the lower ranks. These men then held a closed discussion to choose the new leader.

A Variable Diet

The Teutonic Knights had some earthly pleasures and were especially fond of wine and beer. Letters to the Pope clearly show they followed restrictive food rules like many other holy men. They also enjoyed breaking from those restrictions on feast days whenever the opportunity arose.

Hermann von Salza

The man who took the Teutonic Knights from being a respected fighting force to one of the most powerful bodies in Eastern Europe was Hermann von Salza.

Elected Master of the Order in 1210, he gained the favor of the Holy Roman Emperor. Von Salza successfully led the Teutonic Knights on crusades in Egypt and the Middle East. Recognizing the limits of what they could achieve there, he shifted focus to Prussia.

Expelled from Hungary

The power and influence of the Teutonic Knights often made them unpopular with others. In the 1220s, they were expelled from Hungary because their control of land and castles upset the local nobility.

Conrad von Landsberg

The Teutonic Knights became well known for fighting in Prussia, a region with a strong pagan tradition and fractured local leadership. In the early 1200s, the Order was heavily involved in crusading in the Middle East. Not wanting to give up the opportunity to fight for Christians in Prussia, Von Salza sent a small group of knights under Conrad von Landsberg. They built a castle called Vogelsang (Bird’s Song), establishing the Order’s first foothold in the area.

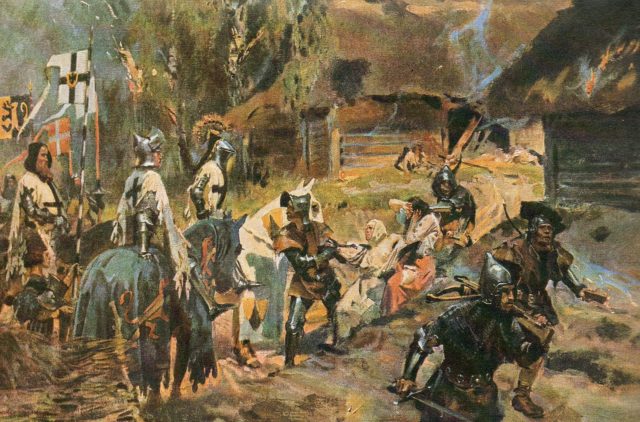

Fighting the Samogitians

One of the toughest fights the Teutonic Knights faced was the Second Prussian Insurrection, which ran from 1260 to 1275. Deciding to fight for their pagan religion, the Samogitians rose up against the Christian forces expanding east across Europe. With crusading forces busy in the Holy Land and secular authorities otherwise occupied, the Teutonic Knights found themselves fighting almost alone for fifteen years, weathering a storm of attacks.

Source:

Jonathan Riley-Smith, ed. (1994), The Oxford Illustrated History of the Crusades.

William Urban (2003), The Teutonic Knights: A Military History.

Terence Wise and Richard Scollins (1984), The Knights of Christ.