The very foundation of the English constitution is based in conflict. Magna Carta, the basis of much English law, was written in a failed attempt to stave off a rebellion against King John. When this peace failed, England descended into a civil war which would include a French prince, a royal death, and a cavalry charge led by a seventy-year-old.

Political Opposition and Magna Carta

King John was not a popular king. His brother, Richard I, had exhausted the royal finances, leaving John to pick up the pieces and take the blame. Cruel, greedy, and insecure, John came into frequent conflict with the nobility.

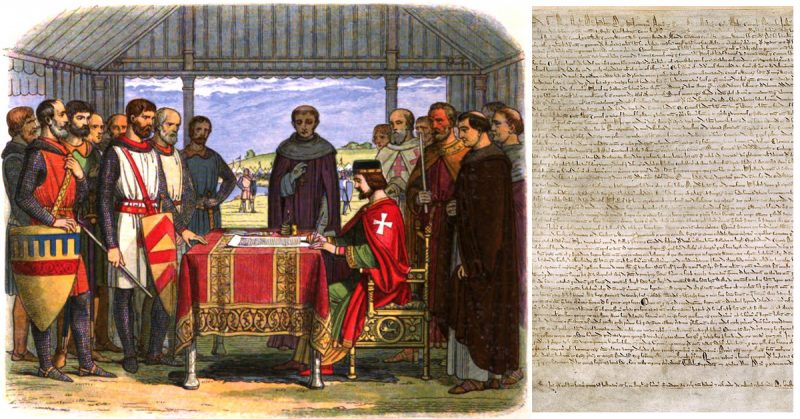

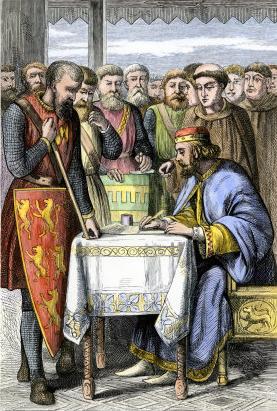

After a decade of rule, effective opposition formed against him. At the time, it was not unusual for opponents to take up arms to shift the policies of a king. The rebel barons seized London in May 1215, and it was clear that extremes had been reached. Trying to avert war, on June 15th, 1215, John signed Magna Carta, a document promising legal reforms which would protect the nobility from his excesses.

A Noble Revolt

The wax was barely dry on the seal of Magna Carta before John started reneging on his promises. The nobles opposing him rose in open revolt, declared John deposed, and offered the English crown to Prince Louis, the son of the French king.

John had been hiring mercenaries from the Low Countries and recruiting troops from his continental holdings. He had control of a network of strong castles. Though he was threatened by Scots to the north, Welsh to the west, French to the south and treacherous nobles throughout his kingdom, it would be hard to dislodge him.

King John on the Offensive

In October, John took Rochester through a combination of undermining and starvation. Rebellious London was isolated.

From there, he proceeded north against King Alexander II of Scotland and the rebel northern English barons who had made the Scottish King their leader. John’s troops stormed Berwick on January 15th, 1216, and raided the Scots to punish Alexander.

Marching hundreds of miles up and down the country, John took one rebel castle after another, while his lieutenants harried the rebels in the Midlands and East Anglia.

Royal Collapse

A storm on May 18th scattered John’s fleet, allowing Prince Louis to cross the English Channel with his troops. John wanted to meet him in a pitched battle, but more experienced men, including the aging veteran William Marshal, persuaded him not to take the risk.

With French support, the rebellion revived. Many in the south-east, who had previously kept out of the rebellion, now rose against him. Many nobles, including four earls, the most powerful men in the land, defected to the rebels.

In August, Louis laid siege to the vital Channel port of Dover, where he was joined by King Alexander and the northern barons. But though they took some of the outer defences, an assault failed.

A Brief Comeback

Emboldened by his opponents’ struggles, King John marched forth again. He drew troops away from the siege of Windsor, relieved Lincoln, and arranged supplies for his castles.

The threat of John heading towards their lands alarmed King Alexander and the northern barons. They left Dover, and the rebel army was once again scattered as each man looked to his own interests.

But just as John was beginning a comeback, disaster struck. He became sick with dysentery, a common problem in medieval armies, and died on October 18th, 1216.

William Marshall Makes Peace

The kingdom was now ruled in theory by John’s son, King Henry III. But Henry was underage, and so William Marshal was made his guardian. The elderly Earl took over the generalship of the royalist side.

Marshal faced many problems. Royal funds were exhausted, the Welsh were threatening the west, and the royalist barons were arguing with each other. Though the rebels’ revolt had been against John, his death did not cause them to give in. So Marshal agreed a truce to last through the winter, giving him time to put the royalist house in order. The price of this truce was ceding castles to the rebels.

Louis Falters

From February to April 1217, Prince Louis was in France, raising reinforcements for his army. During his travels, he was briefly trapped by royalists and guerrillas at Winchelsea.

With John gone and Louis looking vulnerable, two leading rebel barons defected to Marshal, along with many less prominent nobles. Taking the opportunity, Marshal summoned the royal war leaders and recaptured castles they had lost.

When Louis returned, he quickly retook Farnham and Winchester. But with Dover still holding out against him, he was forced to split his forces. While some remained at Dover, others went to besiege Lincoln.

The Battle of Lincoln

Marshall saw his opportunity. Gathering together the royalist host, he marched on Lincoln from the north, taking the rebels by surprise on May 20th. Mistakenly believing that they were outnumbered, they retreated behind the town walls.

The Bishop of Winchester discovered a blocked gate into Lincoln. While other forces distracted the defenders with diversionary attacks, Marshal broke through the gate, once more surprising the rebels. Fierce street fighting ended with a rebel surrender. Forty-six barons and 300 knights were captured, ripping away a huge chunk of Louis’s support base.

One Last Throw of the Dice

With his support crumbling, Louis began to negotiate. Aware that he risked leaving his English supporters in the lurch, he avoided any agreement while waiting for reinforcements from France. But their fleet was caught in the Channel and defeated off Sandwich on August 25th. At last, Louis made peace and returned home.

Throughout the war, both sides had avoided a pitched battle and the risks that it brought. But it was the boldness and battlefield courage of William Marshal, incredible for a man aged around 70, that won the war for his side.