The Hundred Years War was one of the most protracted wars of the Middle Ages. For over a century, the French and English monarchies battled for control of the French nation and the territories of northern and western France. Success in this on-going conflict required strong leadership. So who were the men leading the troops of the Hundred Years War, and how did they go about their business?

Kings – The Top of the Command Structure

At the start of the war in 1337, the command structure was the same on both sides.

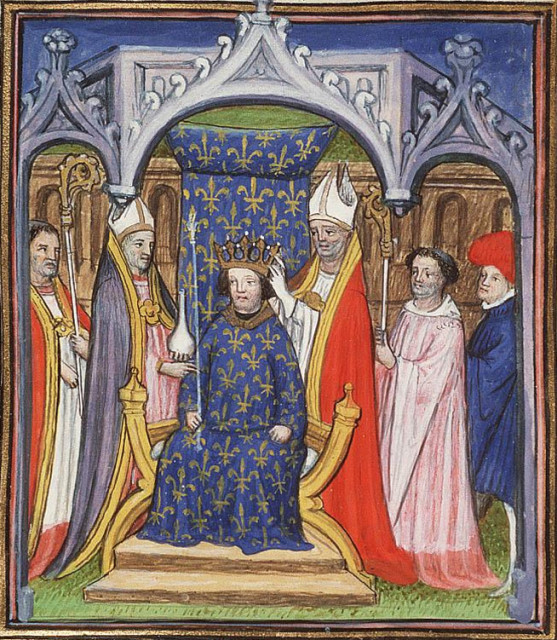

At the top was the king, commanding men in peace as he did in war. He had the right to summon men for war, lead them in battle and punish them for failing to serve. His presence on the battlefield could be a huge motivator, as for the English at Agincourt in 1415. But it also brought risks, as when John II of France became a captive of the English at Poitiers in 1356.

As a result, the whole structure of military command revolved around the royal court. It was from there that most leaders were recruited. Whatever his social station, a man’s best chance of leading an army came from being recognized at court.

High Nobles and High Command

As a result, the top commanders were generally drawn from the high nobility. This was also a reflection of social and political thinking in the 14th and 15th centuries. Nobles were seen as a distinct class, whose God-given role was to lead others.

Many prominent commanders were men of royal blood, brothers or cousins of the king such as John of Gaunt. Even those who did not share grandparents with the king were often related to him through marriage or more distant relations, the nobility having set out down the path of inbreeding that would later cause havoc to royal lines.

Others held their positions because they were too powerful to be ignored. A man such as the Duke of Burgundy, who held so much land and power that he could act independently of the French crown, had to be pandered to and given positions of prominence. Failure to do so could lead to the sort of rebellious activity Burgundy undertook.

Lower Nobility and Professional Soldiering

Beneath the high nobility were the lower nobility. Thanks to feudal recruitment methods, in which men fulfilled obligations to their superiors by providing troops, many of these men arrived for war at the head of fighting units, already embedded in a social hierarchy that had taken up arms.

For the French, these men played a vital role in organizing and leading the defense of territory, using their local authority to raise troops and prepare towns to withstand the English.

Both sides used them as something similar to an officer class, leading soldiers in battle, and as shock troops, due to the superior equipment, they could afford. It was through service in such roles that men could rise above their origins, becoming famous professionals and being paid for their work. Men such as Bertrand du Guesclin and Sir Thomas Dagworth gained prominence through merit more than birth, becoming commanders of royal armies.

Treatises on Leadership

Though thinking on military leadership was less sophisticated that it has since become, there were still popular books and theories.

Most important was De Re Militari by Vegetius. This 4th-century Roman work set out ideas about how war should be fought, putting great emphasis on leadership, moral character, and the role of experience in making soldiers. To a modern mind, a 1000-year-old book might seem out of date, but to medieval scholars its ancient heritage gave its ideas legitimacy.

Military history was also studied for the lessons to be learned. In particular, two 1st century books were popular – Frontinus’s Stratagemata and Valerius Maximus’s Facta et Dicta Memorabilia. Again, the fact that these were works by and about ancient Romans gave them status rather than a sense of irrelevance.

Military thinkers of the age were starting to write their own books, such as Geoffroi de Charny’s Livre de Chevalerie. But these were more concerned with chivalric culture and the moral character of knights than they were with the practicalities of warfare.

Changing Views of Leadership

Though Vegetius’s De Re Militari was a millennium old, its growing popularity was leading to a change in thinking about military command.

The traditional medieval attitude was that leaders were chosen by God, put into their place in society for the good of all. But Vegetius took a different view. To him, positions of leadership should be granted to men based on their merits and experience. They could not just assume a position of power in an army.

This became part of a wider discussion about the nature of nobility. Could it only be inherited, or could it be bestowed? How was a man’s behaviour connected to his noble rank?

In practice, the importance of the war meant that Vegetius’s perspective became more important than it would have been in times of peace. Competent leadership was needed. The fate of the nation could not be left in the hands of ungifted men, whatever their rank.

It was this that allowed men such as du Guesclin and Sir Robert Knolles to gain positions of respect and authority despite their relatively humble beginnings. But still, by the end of the war the high nobility was seeing a resurgence, and at no point were armies being led by commoners.

Charles VII’s Reforms

In the 1440s, King Charles VII of France reformed his army, focusing on placing competent men in command. The results reflected a mix of old and new leadership thinking, with the nobility still firmly in command, but middling nobles given great responsibility. Even these limited reforms could only be achieved because Charles had competent men of high rank. Without them, leadership would have remained as it always had – bound up in and limited by social status.

Source:

- Christopher Allmand (1989), The Hundred Years War: England and France at War c.1300 – c.1450.