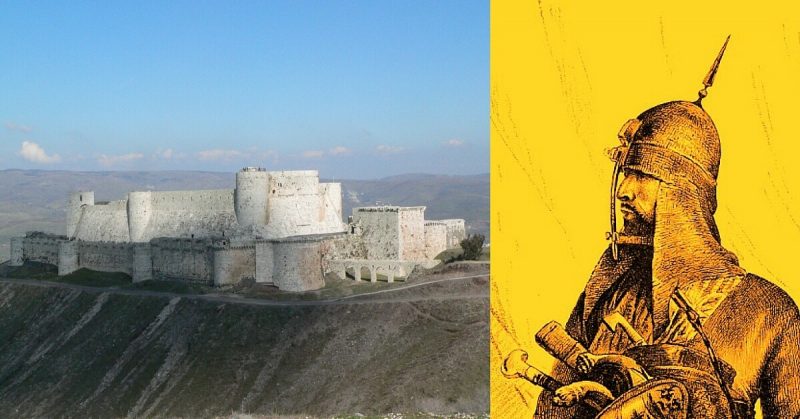

A hulking edifice of sun-bleached stone, Krak des Chevaliers loomed against a clear blue sky. How many men had died to hold those walls, and how many more to take them? On that bright April morning in 1271, it seemed as though the bloodshed might, for now at least, be at an end.

Through the gate they came; a long line of mounted men. They wore burnished mail and surcoats of black wool, and on their chests, they bore the splayed white cross of the Hospitallers.

Their order had once been key in the Crusaders’ conquest – now, the golden age of their dominion was behind them. Many rode without their helms, still more with bloodied features and splinted limbs, but every man held his head high. The Knights, proud even in surrender, surveyed the Sultan’s forces with a cold gaze.

They had held the castle with all their strength and fortitude. In truth, they would have gladly held it longer – died to hold it, even – had it not been for a letter they received the night before.

It would be some time before the garrison of Krak des Chevaliers discovered the truth about the terms of their surrender. The battle had been hard fought, but until the letter arrived there had been little doubt as to how it would end.

In truth, the fall of Krak des Chevaliers began long before the siege.

Sultan Baibars had first marched into the region a year earlier, grazing his livestock on the fields and taking full advantage of those resources on which the castle relied. The Hospitallers knew they faced a formidable opponent; this was a man who marched against the seemingly unstoppable Mongol hordes – and won. Yet he was a subtle tactician as well, and would not go out of his way to engage in unnecessary conflict.

So it was that, even as his armies converged on the Crusader castle, the Sultan turned his men around and retreated. News had reached him of the Eighth Crusade, led by King Louis IX, and in light of these new developments, he withdrew to consolidate his forces. When, a year later, the French monarch died, Baibars knew that Krak des Chevaliers’ time had come.

Once more he unleashed his host upon the region, and this time, his advance seemed truly unstoppable. As he went, the smaller castles in the surrounding region fell to him with little resistance. By the time he reached the Hospitaller stronghold, the chance of a victory against this man seemed to the Crusaders a very slim possibility.

Though drastically outnumbered and facing a renowned military mind, the Hospitallers were not ready to give up the castle just yet. Having offered refuge to many of the local populace within the walls, the Knights shut their gates and prepared for the siege.

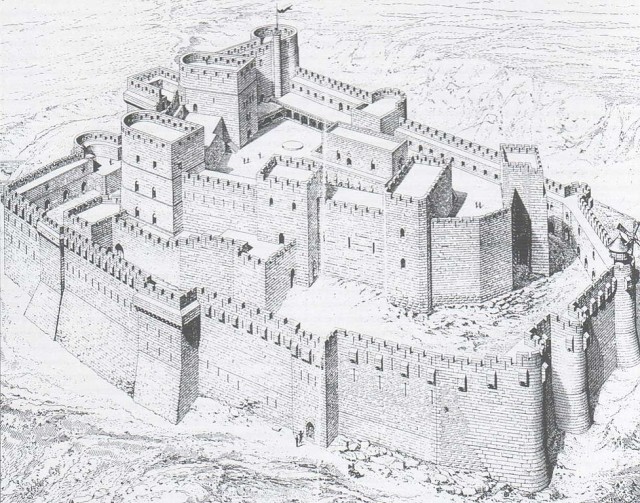

Even with the odds so clearly in favour of the attackers, Krak des Chevaliers itself still offered the Hospitallers some considerable advantages. This was a castle built specifically to withstand long and brutal assaults, with fortifications almost twice the size of some European fortresses. Complete with a large moat, several lairs of towering walls, and a gate accessed only through a long and twisting passageway.

This latter feature offered a particular challenge, as the ceiling of the corridor was lined with murder-holes. Through these gaps, a defender could hurl spears, rocks, and other projectiles, and pour boiling oil or hot sand down on the attacking force.

Knowing just how difficult it would be to even reach the gate, Baibars employed another tactic. After pummelling the castle with siege engines and heavy catapults, the Sultan ordered his men to go underground.

Digging a long tunnel beneath one of the south-western towers, the diggers supported the earth above them with wooden staves. Then, having burrowed beneath the foundations of the tower itself, they packed the shaft with dry straw and the carcasses of pigs and set it all ablaze.

As the wooden supports turned to ash and the ground gave way, the tower above began to sink and crumble. A gaping hole opened up in the outermost wall, and Sultan Baibars gave the order. As one, the vanguard of his infantry stormed the breach, entering the castle’s outer ward.

They faced little resistance – the outermost fortifications was at that point largely home to the local civilians the Hospitallers were sheltering. The Knights themselves withdrew further into the castle, determined to fight on to the last man. The inner wall was a far more imposing affair than the one the Sultan had now captured, and there seemed no easy way to break through or to draw the garrison out.

At that point, the possibility of a long and drawn-out waiting game seemed most likely.

The Hospitallers had access to clean water from their moat and enough food to weather a siege for months, and though their numbers had dwindled considerably, the remaining knights were adamant that they would not betray their order and surrender.

And so it was that, after a ten-day lull in open hostilities, a letter was delivered to the castle. It was signed by the leader of the Hospitaller order, the Grand Master himself. The instructions contained in the letter were quite simple – the defenders must surrender the castle and seek terms with the Sultan and his men.

At once, the Knights within Krak des Chevaliers sent out an party of men to establish the conditions of their surrender. The Sultan, being a reasonable and merciful man, agreed to let every man, woman, and child leave the castle unharmed, guaranteeing both the Hospitallers and the civilians safe passage. With the blessing of their Grand Master, the Knights accepted his proposal and the siege was over.

On that sunny morning in the late spring of 1271, the gates of the fortress opened. The bloodshed was over, the garrison rode proudly forth, and the Sultan’s forces began to mend the damage they had previously dealt to their new conquest. After seeming truly impenetrable for centuries, Krak des Chevaliers had fallen.

In the end, it only took a single sheet of paper to capture the Crusader stronghold. One signature at the bottom of a page changed history forever.

That signature, of course, was not the Grand Master’s.

Accounts differ as to whether or not the Sultan’s own hand forged the letter, but there is no doubt that the order came from Baibars. Wishing to circumvent a long and bloody siege, he employed a far simpler technique. The Sultan decided to simply give the Hospitallers permission to surrender.

In the end, it wasn’t military might or cunning siege techniques that proved the undoing of Krak des Chevaliers – it was a simple forgery, and a scrawl at the bottom of a page.