Artillery shells and bullets whizzing over the trenches created a cacophony of noise. With all of this noise, shouted commands could go unheard. Trench whistles were used to overcome this.

British forces were the first to make use of whistles in the trenches of World War I. The whistles were made by J. Hudson & Company, which was later bought out by ACME Whistles. They continue to manufacture whistles today.

The original whistle was not made for the trenches. The cylindrical whistles which began to be manufactured in 1875 were meant for the Metropolitan Police and were known as “Pig Nose” or the “Glasgow Police Call.” Many police officers at the time attributed their safety on duty to these whistles.

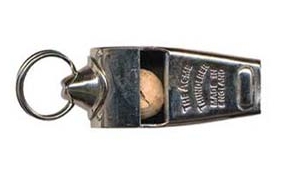

During WWI, the production of whistles changed when J. Hudson & Company created the first military whistle, called the Hudson officer’s trench whistle. These whistles normally had JHudson and Birmingham stamped on them along with the date.

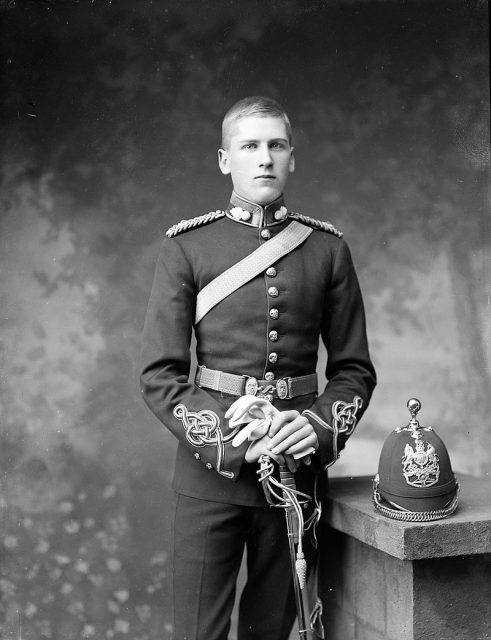

The British army was among the first to use whistles on the WWI front and in the trenches. They were provided to higher ranking officers and had a leather lanyard or strap which was used to keep the whistle from being lost during battle. The initial trench whistle had an average size of 3.15 inches in length and two-thirds of an inch in diameter.

The whistles were used to coordinate movements across companies. Commands for coordinated movements could be relayed down the trenches with greater efficiency. With the din of battle overpowering vocal commands, a sharp trill from the whistles was a better option.

Trench whistles provided a sound that would otherwise not be found on the front. To better communicate, a series of trench commands were created. The one that was used most often was to signal going over the top. Whistles were also used to alert artillerymen that their guns were about to fire so they could avoid injury from the recoil.

While the British military was the first to use whistles in the trenches of WWI, the use of whistles soon spread to the Commonwealth regiments fighting alongside the British, such as Canadian and South African regiments.

American troops also made use of whistles and they were provided to both commissioned and non-commissioned officers. The whistles used by these soldiers were generally made from brass and had a cork ball inside which produced the whistling noise.

The shape of these whistles was also different from the British ones. The American Thunderer design looked like what most people think of when they imagine a whistle, and is the basis for the modern whistle design.

Different whistle designs were provided to the different commanders in the American army. A battalion commander would have a siren whistle while a company commander had a kinglet whistle. Platoon and squad leaders would be provided with Thunderer whistles. This allowed soldiers to determine who the commands on the battlefield were coming from.

Stories of whistles from the front not only provide information about their use in trench commands, but also tell tales of how whistles saved the lives of soldiers. One of these soldiers was Corporal Clucas who fought with the Royal Field Artillery. In France he was hit by enemy fire, but was miraculously spared when a bullet bounced off the brass whistle he was carrying.

As whistles become more common on the WWI battlefields, the demand for them increased. The British government eventually seized control of the factory in Birmingham where the whistles were manufactured to ensure production continued. However, the increased demand combined with an increasing shortage of brass led to a slowdown in production.

To ensure production continued, ACME requested that the government divert some of the steel and tin plate which was heading to Cadbury. Tins for biscuits were shipped from Cadbury to ACME and pressed to make whistles, many of which thus ended up with the Cadbury logo on them.

Read another story from us: Whittling Time Away: Trench Art of WWI

The widespread use of whistles continued in WWII. The whistles of WWII were not only used by officers to signal commands in trenches as had been done in WWI, however. The Air Service used them to signal air raids and the dropping of incendiary bombs, for example. They were also used for emergency signals, and most soldiers were equipped with one.