The prisoners slept on the bare and damp earth. The toilets were insufficient, and the food was in short supply.

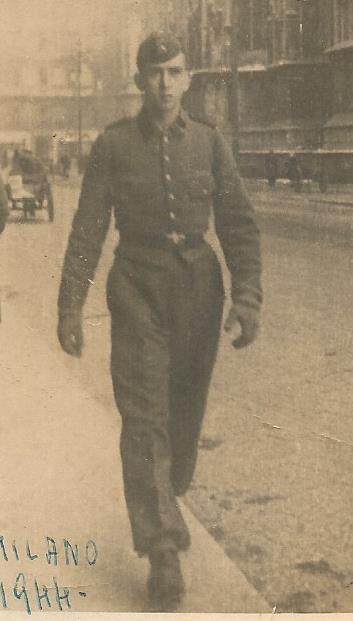

On April 25, 1945, the German troops in Milan surrendered to the Allies. On May 7, in Reims, France, General Alfred Jodl signed the instruments of German surrender signifying the end of the Second World War in Europe.

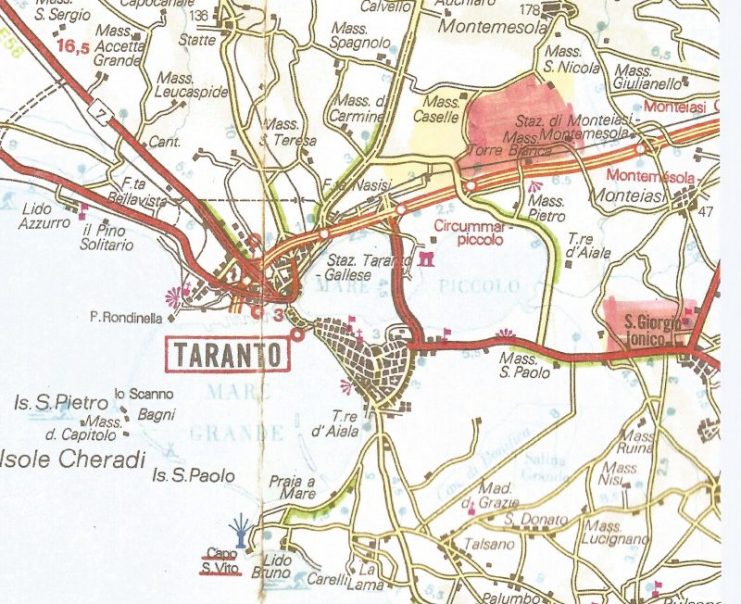

During that period, in the Sant’Andrea area of Taranto, the Allies set up a camp to continue the imprisonment of fascist soldiers, German collaborators, and members of the Decima Flottiglia Mas (Italian for “10th Assault Vehicle Flotilla,” sometimes referred to as “Xª Mas”), a special frogman unit under the command of Prince Junio Valerio Borghese of the Social Republic.

The command of the camp was entrusted to the British, but the garrison consisted of an Indian Army unit.

Sant’Andrea was intended as a transit camp. In fact, the prisoners were transferred to Algeria where they were kept for at least six months before they were freed to return to their homeland.

At the camp, there were Italian soldiers already taken prisoner by the Germans in the Aegean and the Balkans. The prisoners held by the British in Africa and India were faithful to the King, Vittorio Emanuele III, were repatriated to their families before those who were faithful to the Duce.

The latter group of prisoners was continually told: “tomorrow – when the ship arrives.” Their wait was unnerving, and their repatriation came months later.

A veteran remembers

Severino De Prosperis was a veteran from the Aegean. He recalls his return to Italy after his imprisonment in Cos, an island in the Dodecanese:

“It was July 10, 1945, when, with the ship Ville de Orange, we returned to Italy. Entering the Mar Grande, in Taranto, the emotion mixed with euphoria came over us. After three difficult years, we finally returned home. When the ship entered the revolving bridge channel, people from the seafront began to whistle, scream, call us fascists, throw tomatoes, and anything else that could hurt our feelings. We did not understand that behavior. We noticed it when the ship docked and we disembarked.

“There were Indian soldiers who forced us to get on their trucks to move us to a camp beyond the Mar Piccolo, towards the hill, Campo Sant’Andrea. We then learned that in that center, fenced with barbed wire and wooden spikes (cheval de frize), controlled by sentries, there was a mixture of fascists and sailors of the Xª Mas. There, we were interrogated by British officers. They asked us what we did after September 8, 1943. With my German card I proved that I was a worker.

“Luckily I was [separated] from the others who had joined the German Army. These were punished by sending them to Algeria to camp 311 where they stayed seven months before returning to Italy permanently. After a couple of days, I was transferred to the Santa Teresa camp, in a pine forest East of Taranto, towards San Giorgio. We were free to move; there were no fences. I stayed there a couple of days. On August 2, 1945, I finally returned to Fiuggi by train.”

The Camp

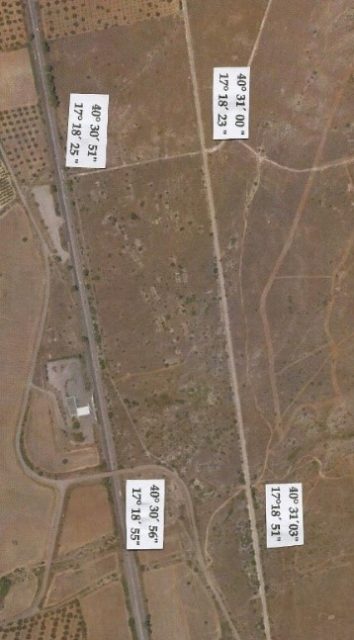

Sant’Andrea camp, also known as “Campo S” or “Hunger Camp,” was located North of Mar Piccolo, in the area of four farms: Caselle, Torre Bianca, Sant’Andrea and Torre Rossa. The foundations of the barracks, part of the sewage and road system, as well as the route of the fences are still visible.

The shelters were called “pen” (chicken coop), and the prisoners spent endless hours in terrible idleness.

Photos above: On the map, the foundations of the shelters are visible.

The prisoners slept on the bare and damp earth. The toilets were insufficient, and the food was in short supply. According to local news, about half of the 20,000 men who passed through there died.

The field was surrounded by two barbed wire fences and a path for surveillance. But it was not enough to block the escape of the most daring.

On one occasion, a dozen of them found shelter in the home of a car engineer in the Old City of Taranto, and his relatives brought them food. They avoided being discovered by informers who, for personal gain, could have put everyone in danger.

Little is known about the history of Sanslflskt’Andrea camp, although some new information was recently revealed by a priest who spent much of his time helping the prisoners.

A fresh study conducted by Dina Turco, a researcher from Taranto, made public what was happening in the era and in that camp.

The first prisoners came from Afragola, near Naples, from an Allied camp. They arrived in Taranto on May 4, 1945, in cattle wagons. They were given only empty bins to deal with their personal needs. Some of the prisoners jumped off the running train.

Four days after their arrival, on June 8, they were put on a ship, the Duchess of Richmond, to be transferred to the camp in Algeria where they remained for eight months. Many fell ill with dysentery and other infectious diseases.

Their return to Italy should have meant the end of their suffering. Instead, after traveling back on the Strathaird steamer, they were put on trial for any war crimes committed during their service.

The prisoners lacked food and health care. During the day, they would walk along the fences, asking for something to eat. The inhabitants in the neighboring areas and the relatives who had learned of their presence in the camp brought food and clothing to help them.

Such items were delivered with the help of the field guards who required bribing and, very often, kept the goods themselves. Limited contributions were also provided over time by the Catholic Church.

An excuse for rioting

On one occasion, on April 4, 1945, an incident occurred that provoked a riot. An elderly lady had gone to the edge of the camp where she began to shout her son’s name. When she saw him, she threw him a bundle containing food and a few other things.

Unfortunately, she was rather weak, and the package became tangled in the fence. The man, ignoring the order of the sentry, approached the fence and was seriously injured. This triggered the riot.

Part of the fence was broken, but the situation was soon back to normal. A few days later, the camp was handed over to the Italian authorities. The prisoners were freed and the field dismantled.

The bitterness of the loosers

A famous Italian comedian, Giorgio Albertazzi, one day said: “I went to Salò (Republic of Salò) like many guys, convinced that we were fighting for Italy, but in our minds aware that at that time we were on the side of those who had already lost.”

This was a thought that was in the mind of many young Italians who had kept faith with Mussolini, despite knowing their end would soon come.

The Italian institutions were highly criticized for the lack of assistance given to the prisoners and for the disinterest they showed in the prisoners’ prolonged isolation. At the end of the war, new Catholic-communist political ideas were in the ascendancy. Many wanted revenge for what had happened.

However, to avoid the participation of thousands of prisoners in the referendum for the Monarchy or the Republic, those men had their segregation prolonged. This was the treatment granted to men who had the misfortune to fight honestly and proudly on the losing side.

All photos are provided by the author.