While the far more well-known 54th Massachusetts Infantry regiment is usually portrayed as the first African-American unit of the American Civil War to have seen combat, the truth is that another African-American unit beat them to the post, going into battle two months before the 54th Massachusetts’ assault on Battery Wagner, a part of the Confederate fort at Port Hudson.

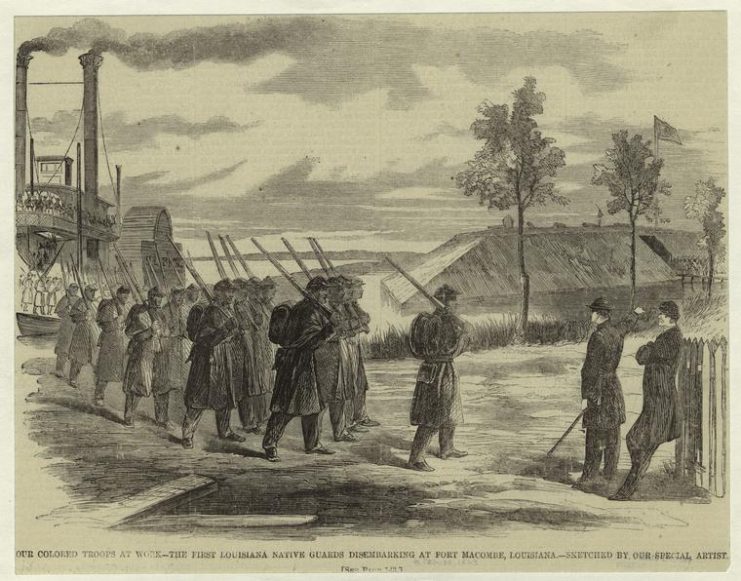

The Louisiana Native Guards, a Union infantry regiment composed of African-American and mixed-race troops, with both white and black officers, assaulted Confederate fortifications at Port Hudson, Louisiana, on May 27, 1863. Thus it became the first African-American regiment to see battle in the Civil War.

Interestingly enough, the Louisiana Native Guards started out as a Confederate unit. Shortly after the Civil War began, a group of free black and mixed-race men who resided in New Orleans held a meeting to discuss where they stood in terms of the war that had just broken out.

They decided to form a unit and volunteer to fight for the Confederate government, primarily because at that time New Orleans was part of the Confederacy.

It may seem strange to imagine that any African-American would have wanted to fight for the Confederates, who were against the abolition of slavery. However, all of the men who volunteered for the Louisiana Native Guards regiment were free men, and many were of a mixed racial background. Some had been free for generations and were successful, wealthy businessmen.

What was more, in Louisiana, formerly a French territory, slavery laws had long been different from those in other southern states. Its laws required slaves to be treated more humanely than they were under the horrific chattel slavery prevalent in neighboring states, and in Louisiana easier avenues to freedom for black slaves existed than in other states.

Slaves in Louisiana also had the right to marry and the right to not be separated from their families. Interracial marriages, although illegal, were common enough.

In New Orleans there was a particularly high concentration of free African-Americans and people of mixed racial heritage, many of whom were very highly educated, owned property, land and businesses, and in some cases owned slaves of their own. This did not mean, of course, that most of them did not see slavery as the abomination it was – it just meant that things were more complex than in other states or cities.

Why these free African-Americans chose to fight for those who were in favor of maintaining the horrible institution of slavery remains a matter of significant debate. Some theorize that the free black and mixed-race men who volunteered for the Louisiana Native Guards wanted to advance their own or their families’ positions in a segregated society, while others think that they may simply have feared spiteful reprisals if they did not answer the governor’s call for volunteers.

Whatever their reasons for doing so were, 1,500 men ended up volunteering for the Native Louisiana Guards. While the Confederate government initially acted as if it were thrilled that these men had volunteered to fight for the Confederacy, the specter of racial prejudice soon reared its ugly head.

As the question regarding the abolition of slavery in America became an increasingly prominent issue in the war, many Confederate leaders felt that to justify the continuation of the practice of slavery, it was necessary to promote the idea that black men were inferior to white men.

Having a black unit fighting alongside them would negate their belief in white superiority, and therefore they ultimately denied the Louisiana Native Guards the ability to fight for them in battle.

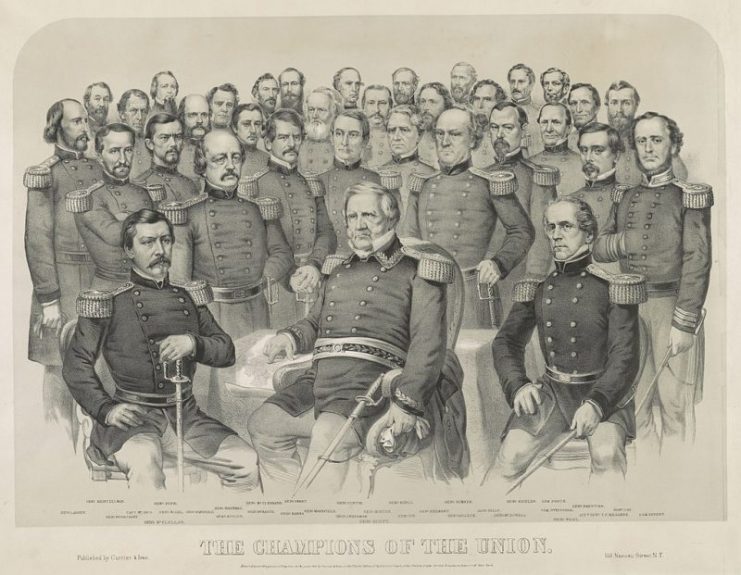

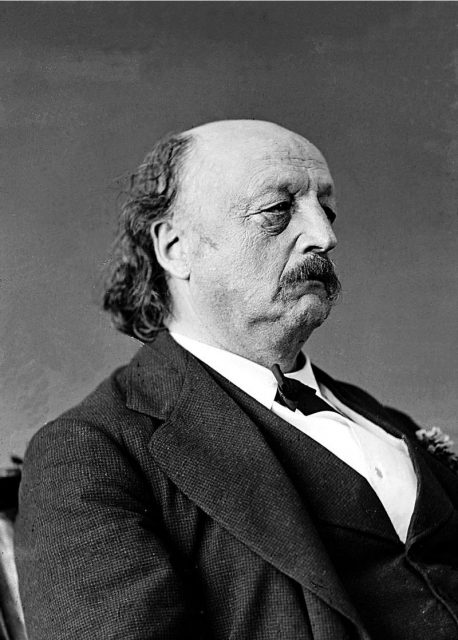

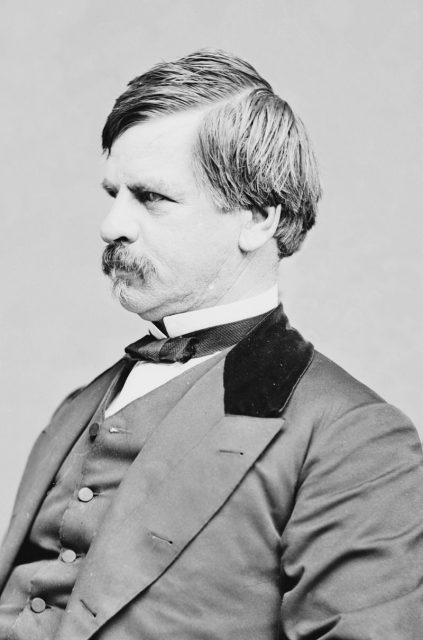

Around a year after the Louisiana Native Guards had been formed – and then disbanded – New Orleans surrendered to the United States Army and Navy. The Union commander, Major General Benjamin Franklin Butler, an abolitionist, decided to see if he could swell the ranks of his Union forces with local volunteers – specifically, men of color.

The men of the Louisiana Native Guards, who had been humiliated a year earlier by the insulting snub they had received from the leaders of the Confederacy, were only too eager to join up. Now that they felt their futures and positions in society were secure, they wanted to fight against those who wished to preserve the unjust and abominable institution of slavery.

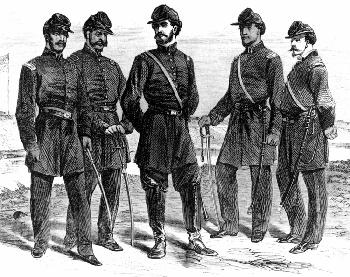

Within a few weeks over a thousand men had signed up. While rules stipulated that only free black men could join, many officers were willing to look the other way and allow runaway slaves, who also came in droves, to join the regiment. On September 27, 1862, the Louisiana Native Guards became the first black regiment to be officially mustered into the Union Army.

Many of the black officers of the regiment were some of the most well-educated, wealthy and highly-respected men of New Orleans, and they were itching to go into battle against the Confederates to prove just how wrong the Confederate leaders had been about their supposed lack of capabilities.

One of these men was Captain Cailloux, who was fluent in both English and French, and who had been educated in France – an education which had included extensive military training.

In May 1863 the men of the Louisiana Native Guards got their chance to taste battle. Now under the command of Major General Nathaniel Banks, the regiment was brought in to assist with the assault on Port Hudson, a Confederate stronghold on the Mississippi.

The stronghold had been fortified extensively – using slave labor – and the men knew that breaking through the fortifications in a frontal assault was going to be a difficult task. Nonetheless, every man of the Louisiana Native Guards was prepared to give his all in the effort to take the fort. Waiting to take on the Union troops were around 6,000 Confederate soldiers, supported by 31 pieces of field artillery and 20 siege guns.

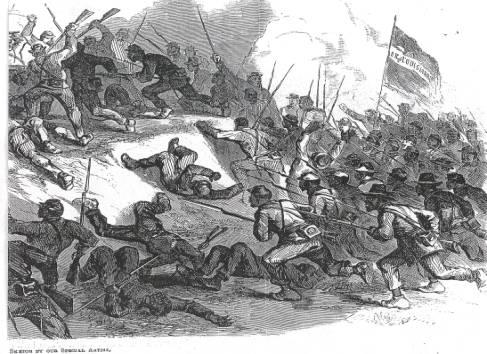

From the early hours of the morning Union cannons pounded the fort in preparation for the attack, and at 10 AM the bugle call signaled the advance. The Native Guards charged at a run across half a mile of broken ground, and were hammered with artillery fire from all sides as they advanced.

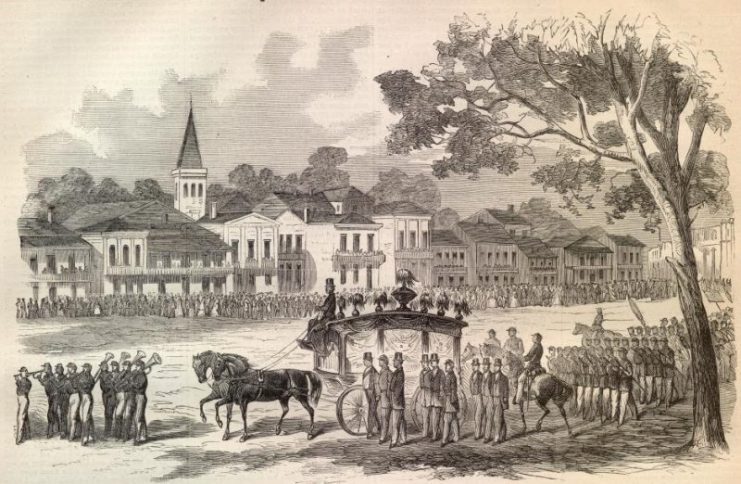

Determined to prove their courage, they pressed on, refusing to back down even as Confederate troops began to pepper them with musket volleys when they got into range. Captain Cailloux’s arm was shattered by a musket ball, but he nonetheless pressed onward, crying out to his men to follow him and take the fort. A shell hit him next, though, ending his life.

After finally being driven back by musket volleys at near point-blank range, the men of the Native Guards reformed and charged again, even though their ranks had been decimated. They were unaware that they were now the only Union unit attacking the fort.

Totally unsupported and heavily outnumbered, they continued their brave assault, jumping into and swimming across the moat in full view of the enemy in their eagerness to attack. Yet again they got to nearly point-blank range before they were driven back by withering fire.

Read another story from us: The Real Louisiana Tigers

A third courageous charge resulted in the same outcome, and after this the Native Guards were finally ordered to withdraw – which they did in good order, marching off the field of battle in formation, as if on parade, even as the enemy continued to fire on them. After this heroic if futile display of tremendous courage and fighting spirit, nobody could in good conscience believe that black troops were in any way inferior to white soldiers.

After the Louisiana Native Guards had blazed this initial trail, 180,000 black men ended up fighting for the Union over the course of the Civil War.