The Battle of Bosworth Field was fought on the 22nd of August 1485 outside the small town of Market Bosworth, England. It was one of the most important battles in English history.

Constituting the climax of the Wars of the Roses, it ended decades of conflict over the throne and brought stability to a nation torn apart by war.

The Wars of the Roses

The Wars of the Roses began in the 1450s when the weakness of King Henry VI led to rival factions competing to control the throne. King Henry’s own House of Lancaster was led by a group of nobles centered around Queen Margaret, who wanted to protect her own influence and the future of her son. Opposing them was a faction led by the Dukes of York.

Years of war and political maneuvering eventually placed the younger Duke of York on the throne as King Edward IV, following victory at the Battle of Tewkesbury in 1471. But when Edward died in 1483, his son was too young to rule, just as Henry had been at the start of his reign.

Edward’s brother seized the throne, becoming King Richard III. In securing his position, he seized and killed prominent noblemen, as well as his own nephews. Having alienated significant parts of the nobility, he had set the stage for fresh war.

Coming to Bosworth

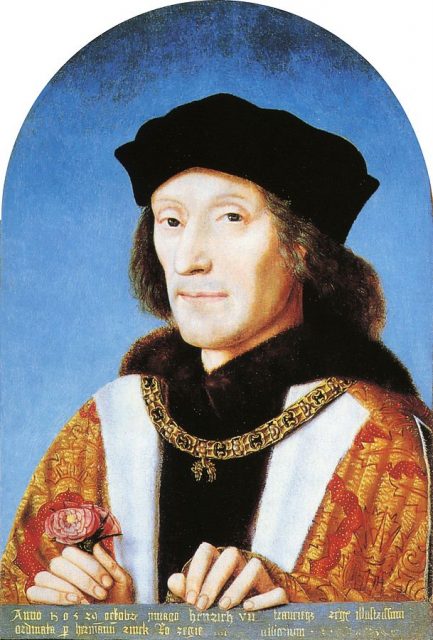

Those disillusioned by Richard’s rule rallied around the remaining Lancastrian claimant for the throne: Henry Tudor. He planned to return from exile, seize the throne, and marry a descendant of the Yorkist line, finally bringing peace and unity.

His first attempt was thwarted when storms delayed his crossing and an insurrection in the West Country was swiftly put down. But more allies rallied to Henry, while Richard prepared for the inevitable invasion.

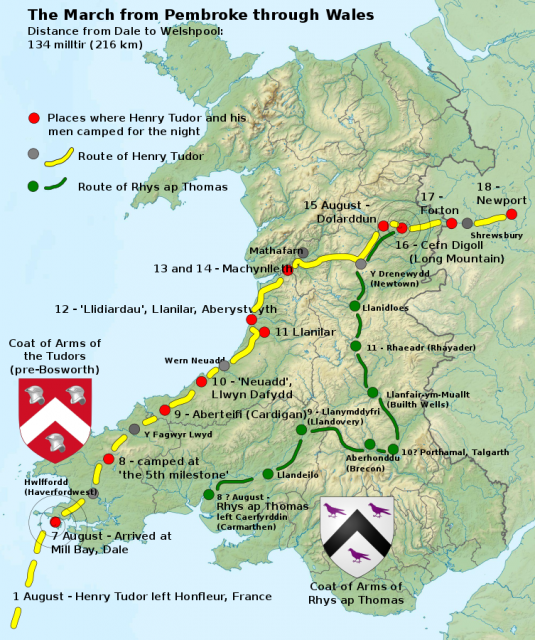

Henry arrived at Milford Haven in August 1485. Family connections caused many in Wales to rally to him. From there he marched east into England, accruing troops as he went.

By mid-August, several prominent nobles had deserted Richard, taking their soldiers with them. However, he lacked neither courage nor manpower, so he marched forth from his rallying point at Nottingham, set on defending his throne.

The Armies

Three armies met at Bosworth on the 22nd of August. The largest was Richard’s, consisting of around 8,000 English soldiers. Then there was Henry’s rebel force, consisting of 2,000 French mercenaries plus Welsh and English rebels, giving a total of around 5,000.

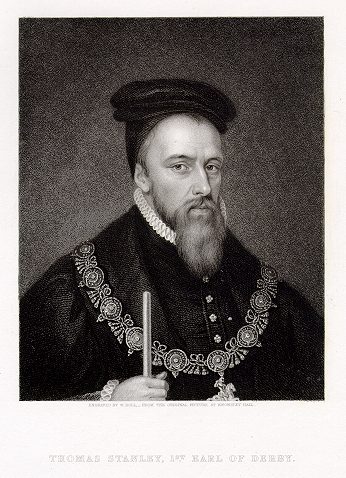

The third, led by Lord Thomas Stanley and his brother, Sir William, was the smallest with 4,000 men. Lord Stanley had met with Henry Tudor and was sympathetic to his cause, but Stanley’s son was in Richard’s hands, making him unwilling to commit against the king.

The armies consisted mainly of infantry carrying spears, billhooks, and other polearms. There were also hundreds of archers and some men equipped with early handguns.

The elite of the armies were the men-at-arms – knights and other wealthy warriors equipped with heavy armor, hand weapons, and warhorses. They were supported by cannons firing lead, iron, and stone shot.

A Clash of Arms

As the armies approached each other, Richard, an experienced soldier and able tactician, acted quickly to place his troops in good positions on high ground. The men-at-arms left their horses in the rear to join the battle line.

Both Richard and Henry sent messengers to Lord Stanley calling him to their side. He acted on neither, hedging his bets against the outcome of the first clash.

Henry’s advance in column was delayed as he negotiated marshy ground. If Richard had seized this opportunity, he might have attacked while his enemy was vulnerable, but instead he held his position.

Once in line, the two sides bombarded each other cannons and bows. While doing little damage, this disrupted formations and encouraged men to close to the attack.

At last, the armies met. Bloody hand-to-hand combat ensued, the two lines pressing against each other, men fighting desperately with sword, bill, and flail.

Henry played little part in the fighting, leaving command to the more experienced Earl of Oxford. Richard was always near the heart of the action, directing his men with skill and vigor.

The Stanleys’ Attack

After more than an hour of brutal combat, the fate of England still hung in the balance. Both sides were pushing in their reserves to keep the lines strong.

But on Richard’s side, the Earl of Northumberland, commander of the rearguard, refused to commit his men to combat. Though he had marched to war with Richard, now he would not fight for him – one more desertion on the heap of those that had come before.

At last, the Stanley’s made their move. Sir William’s forces charged in, attacking Richard’s men. The tide of battle swung against the King.

Many times in the Wars of the Roses, leaders had taken flight when the battle turned against them. Not so Richard III. He fought to the bitter end, his blood mingling with that of the men who had fought for him.

According to one version of the story, he died while trying to ride down Lord Stanley, set on punishing his betrayal. A more popular version says that he died during a desperate attack on Henry and his retinue.

The End of the Lines

With Richard dead, his army collapsed and the battle was over. 1,000 men had died on the royalist side, 200 on that of the rebels.

Richard’s gold circlet was found and placed on the victorious leader’s head by Lord Stanley. Henry Tudor was now King Henry VII, who would soon marry Elizabeth of York. The lines of Lancaster and York ended, replaced by the House of Tudor, one of England’s most famous dynasties.

Read another story from us: No Games of Thrones – The Real War of the Roses

Two years later, the Wars of the Roses saw one last battle, as Henry put down Lambert Simnel’s rebellion at Stoke. But it was at Bosworth Field that the Yorkist dynasty ended, Richard III lost both his kingdom and his life, while England finally found a ruler to unite behind.