With just his fists and his knife, he managed to fend them off, fighting with such fury that the Germans eventually retreated.

While the United States only ended up fighting in the First World War for just over one year and seven months, this relatively short period managed to produce a number of extraordinary American heroes.

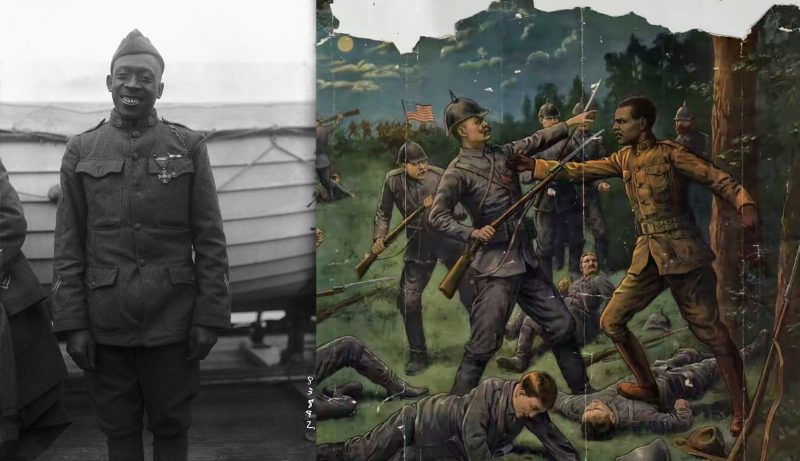

One of these was Sergeant Henry Johnson, the first American in history to receive France’s highest award for courage and valor: the Croix de Guerre avec Palme.

He was also awarded America’s highest decoration for valor, the Medal of Honor, for the astounding bravery and grit he showed in single-handedly fighting off a group of German soldiers in the Argonne Forest in May 1918. But this latter award was only conferred on him almost a hundred years after his act of incredible courage.

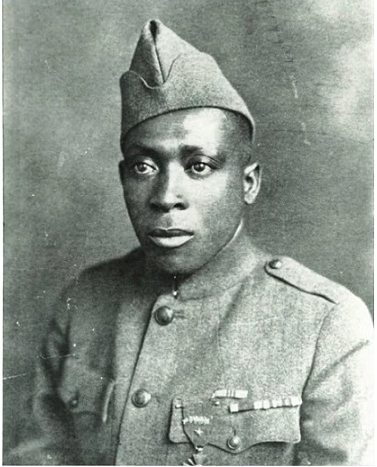

The exact date of Johnson’s birth remains unknown, but it was likely sometime in the 1890s in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. He was named William Henry Johnson at birth, but preferred to go by his middle name, Henry. He grew up poor, and prior to enlisting in the US Army, he worked as a luggage porter at Albany Train Station in New York.

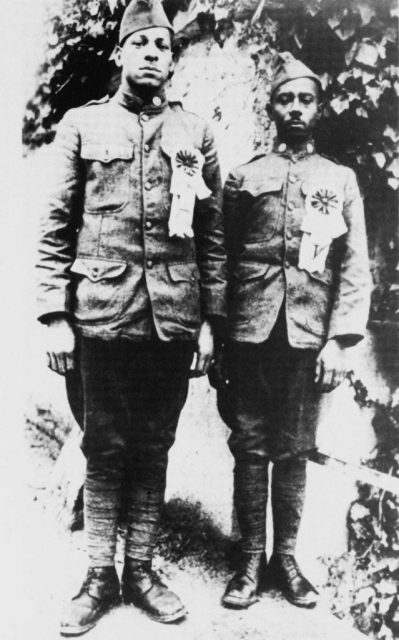

His life changed dramatically on June 15th, 1917 – the date on which he joined the New York National Guard 15th Infantry, a regiment of African American soldiers.

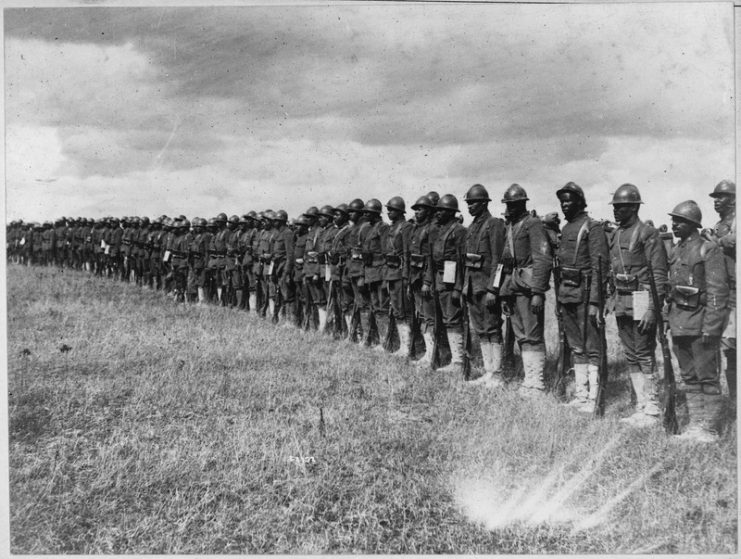

When the regiment, based in Harlem, was officially mustered into the army, they were redesignated as the 369th Infantry. The unofficial nickname they later earned was “The Harlem Hellfighters.”

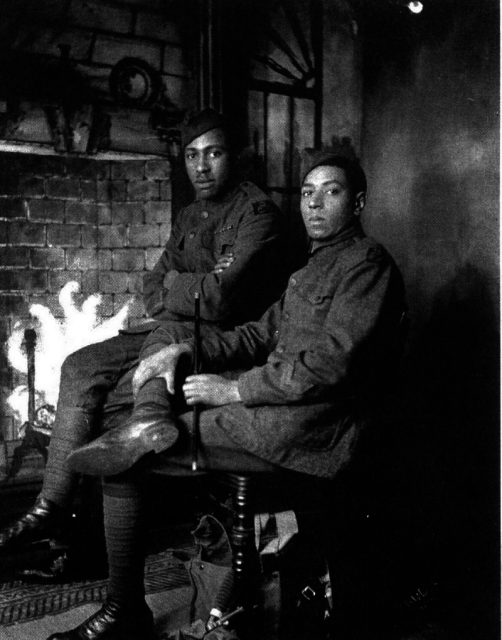

Military life for the African American men of the 369th was a challenge from the outset. During their training in South Carolina, they were subjected to racist attacks, abuse, and harassment. The perpetrators were a number of white soldiers who were vocal about their refusal to fight alongside black troops.

When the 369th finally arrived in Europe, they were given shovels instead of rifles and made to do menial labor instead of fighting alongside their white compatriots in the trenches.

While American military commanders may have been reluctant to send black troops into combat, their French counterparts had no such reservations. The French army suggested that since the 369th was not being used in the trenches by the American command, they could use the men in their own trenches.

General Pershing acquiesced to this request. Johnson and the other men of the 369th were happy to finally get their hands on rifle, bayonets, and grenades, even if it meant that they had to wear French uniforms and be under French command.

The French deployed the 369th to Outpost 20 on the edge of the Argonne Forest. It was here that Henry Johnson would perform his act of amazing valor.

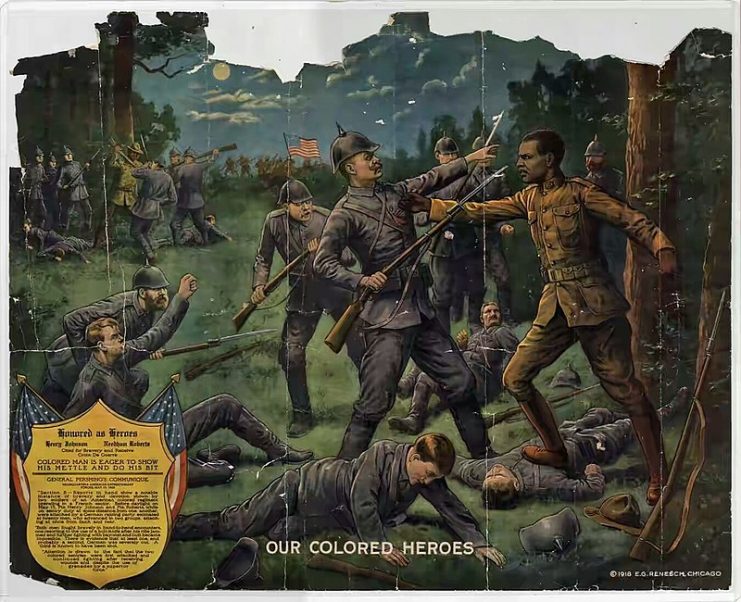

On the night of May 14th, 1918, Johnson and another soldier, Needham Roberts, were on sentry duty at an observation outpost in the forest when a German raiding party launched a surprise attack. Roberts was wounded and incapacitated early in the attack, leaving Johnson on his own to face the attackers who numbered at least twelve men, if not more.

Johnson managed to toss a grenade and get off one shot with his bolt-action rifle – a shot that took one German out of the fight. But reloading was impossible as the Germans were right on top of them.

Forced to fight in a vicious hand-to-hand battle while outnumbered twelve to one, Johnson launched himself into the fray using his rifle as a club. When it was ripped out of his hands, he whipped out his bolo knife, with which he managed to stab at least one of his attackers in the head.

With just his fists and his knife, he managed to fend them off, fighting with such fury that the Germans eventually retreated.

During the encounter, Johnson was shot three times but kept fighting. He ended up with 21 wounds from German knives and bayonets.

His heroism ended the German raid before it even had the chance to begin and saved Roberts from being taken prisoner. Even more astonishing was how Johnson, a relatively small man at five foot five and 127 pounds, managed to fight off so many men single-handedly.

For this act of heroism, the French did not hesitate to award Johnson their highest decoration for valor, the Croix de Guerre avec Palme. Johnson became not just the first African American to win this award, but the first American in history to win it.

His own country, sadly, was not so quick to reward his astonishing courage. While he was promoted to the rank of sergeant after this incident, he did not receive any American decoration for valor – at least, not until almost a hundred years later.

When his story got into the hands of the American press, his daring and courage were celebrated in a number of newspaper articles. When he returned home, he and the men of the 369th – who had served in the trenches longer than any other American unit – were permitted to participate in a victory parade in New York in February 1919.

![Famous New York [African American] soldiers return home. [Henry] Johnson, one of heroes of New York’s [African American] 369th (old 15th) regiment, passing along Fifth avenue during parade. He is standing in automobile with bouquet presented to him](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2019/02/famous-new-york-african-american-soldiers-return-home-henry-johnson-one-of-heroes-of-new-yorks-african-american-369th-old-15th-regiment-passing-along-fifth-avenue-during-parade-he-is-stan-741x587.jpg)

Initially, Johnson went along with this, but one evening in St. Louis he broke down and told the audience the truth about the fact that the men of the 369th had been on the receiving end of much racial abuse. He described how many white American troops had refused to fight alongside them.

After this, Johnson quit his lecturing tour and was not asked to return.

His story ended in quiet tragedy. After his wife left him, his permanent health issues – the result of his war wounds – led to a downward spiral into despair and alcoholism, a sadly typical story with many war veterans.

Although supported by an Army disability grant and receiving Army-sponsored help at a number of medical facilities, he died of myocarditis on July 1st, 1929.

Over the following decades of the 20th century, many veterans and civilians campaigned to have his valor officially recognized. Their efforts eventually paid off when, in 1996, he was posthumously awarded the Purple Heart.

In 2015, his heroism finally got the full recognition it deserved when he was posthumously awarded the Medal of Honor.