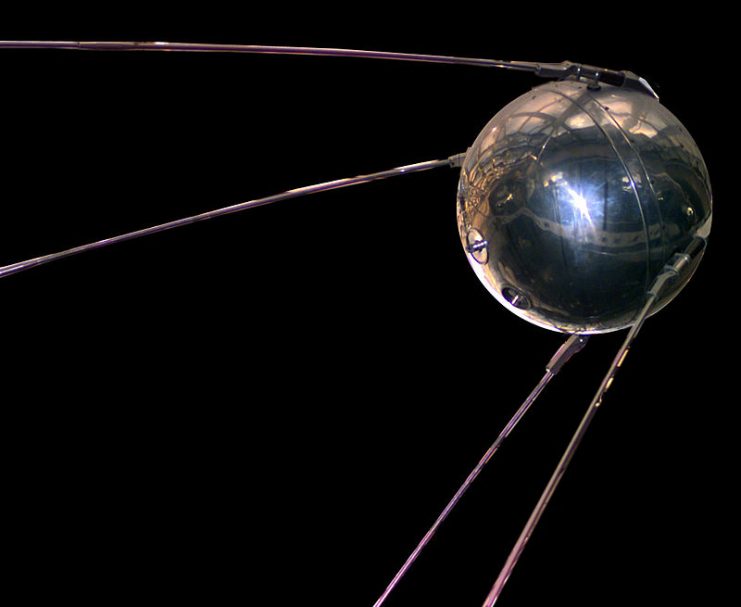

Mere months after Sputnik terrified Americans and signified the early Soviet lead in the Space Race, the American military came up with a bold, and perhaps absurd, response.

The American government felt that it needed to send a message. This response had to be visible to the whole world, it had to be a show of force, and it had to be more impressive than just copying the Soviets by sending up a satellite. America decided to nuke the moon.

Although the United States military has still not technically acknowledged that they were involved in the creation of this plan, code-named Plan A119, several sources have come forward to discuss it. Most famously, it was revealed in Carl Sagan’s posthumous biography that he had been involved in the project.

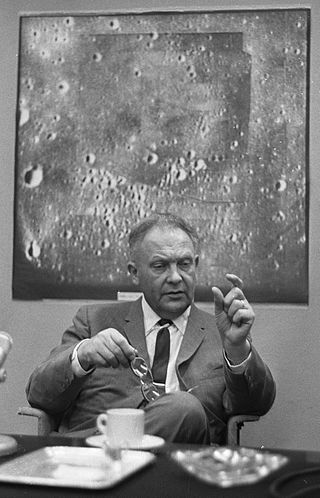

His biographer only learned of the project because Sagan had violated the confidentiality standards he was meant to follow by listing the plan as research experience on an application for a graduate fellowship. At the time, Sagan was only a doctoral student and was working on the project with his mentor, Gerard Kuiper, under the direction of Leonard Reiffel at the Illinois Institute of Technology.

Shortly after the biography was published, Reiffel himself acknowledged the project in an interview with The Observer, where he discussed the goals, practical considerations, and science behind the project.

Theoretically, the plan was plausible. At one point, the NASA scientists involved believed that the strike could be accurate within a two-mile radius. By 1958, when the project was created, hydrogen weapons had been developed to surpass more old-fashioned fission bombs. Nonetheless, one of these older fission bombs, similar to the one used on Hiroshima, was to be used for this mission because of its lighter weight.

A hydrogen bomb would have been too heavy for the intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) that would carry it to break the atmosphere. Even the smaller bomb would have caused a bright enough flash and kicked up enough debris to be visible from Earth. The goal would be primarily to one-up the Soviets, but some scientists were also excited about the prospect of learning more about the crust of the moon and revealing more about how nuclear weapons would work in space.

However, this all ignores the obvious strategic problems with nuking the moon. It would not only be an expensive endeavor but would also lead to the militarization of space and the moon. Scientists were also concerned that the explosion would ruin the surface of the moon and potentially kill any microorganisms that might live there (as some scientists believed was possible at the time).

Later plans to measure the background radiation on the moon would also have been foiled. Reiffel himself had objected, stating that he “made it clear at the time there would be a huge cost to science of destroying a pristine lunar environment, but the US Air Force were mainly concerned about how the nuclear explosion would play on earth.”

Project A119 was soon abandoned due to the conclusion that the public would respond negatively to an attack on the moon. Indeed, when the plan was revealed in the late 1990s, the public responded either with mockery or distress to what would have ultimately been nothing more than a pointless outburst of violence in response to falling behind in a space race.

Less than a decade after the plan was scrapped, the Outer Space Treaty and numerous other agreements were signed to prevent the militarization of space, indicating that global consensus had become hostile to any such idea. Instead, the government refocused on the much more popular goal of a moon landing, and the rest is history.

The equivalent Soviet project, code-named E4, was similarly canceled. Although less is known about Project E-4, and documents pertaining to it have only been publicly revealed in the past decade, it is thought that the project was abandoned for similar reasons to the American project. Additionally, the Russians were concerned about the potential failure of the launch and the resulting danger to civilians.

Although the A-119 Project was short-lived, some of the scientific goals of the project were, and still are, of real interest to scientists. As recently as 2009 NASA sent a kinetic energy impactor called “Centaur” to the moon to hit the surface as a means of learning more about its depth and composition. This mission was partially successful, as water was found on the moon, but it did not create a big enough impact to obtain the samples that NASA wanted.

Read another story from us: Project Stargate: The name of a secret unit of the US military

As far as is publicly known, there is no plan to use a nuclear weapon to get a larger impact. However, the partial success of NASA’s mission to explore the moon’s crust further does raise the question of what they might do in the future to achieve deeper penetration and better samples. Whatever NASA decides to do, it will require a more powerful explosion than that which was created by the 5,600 mile per hour impact of Centaur.