I like to think I’ve been open about my disappointment with the way the centenary of the Great War was handled in the UK.

Four years of endless plastic sorrow stirring up a queasy mix of futility and fudge were our lot. We might have taken the opportunity to remember the thousands who came home to live again, but no, all we got was maudlin grief for the dead.

The opportunity to celebrate the living and recall their experience to remind us that their lives were more than just the sum of a war was thrown away. Sometimes it was difficult to recognise there was a victory at all. I know quite a number of historians and aficionados of the Great War who feel the same way as I do. But it’s done and good riddance.

There is no need for interpretation and saccharin reflection when we read the prose of a man who was there, who lived and was able to record his experience in exceptional style. This awfully beautiful book by WV Tilsley does the job perfectly.

Other Ranks first appeared in 1931. It had been in gestation for a number of years but the author was filled with doubt over what to do with it. He had seen a forest of first-hand accounts and other tales of daring do appear and he seems to have decided to wait out, but he had a change of heart and got his book published. We are the winners.

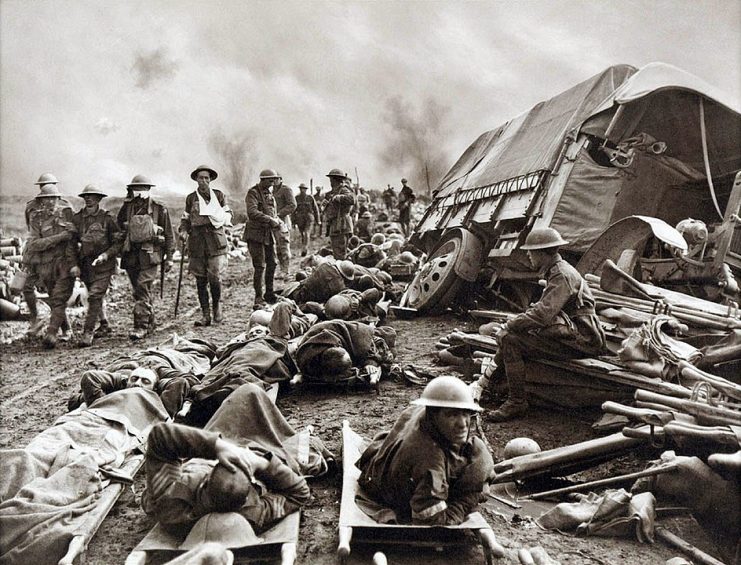

William Vincent Tilsley was born in 1896 and had begun a career in industry when the Great War intervened. He found himself in uniform and after training he was off to France to take part in the Battle of the Somme.

After that he performed a number of tasks before heading to Flanders where he endured Third Ypres in 1917, better known as the Battle of Passchendaele. The experience forms the backbone of his account of the war, which he based on a surreptitious diary and notebooks he filled during his time out in France and Belgium.

Bill Tilsley’s war is told with names changed to protect the real characters from any embarrassment. He becomes Bradshaw, writing in the third person, but aside from the names and a few physical details, all the people we encounter were very real.

Tilsley was a Lancashire lad and his book is infused with the local vernacular, but it does not hinder appreciation in any way, if anything it adds to the charm. The attention to detail is incredible and the writer’s ability to set scenes and paint pictures is stunning.

The quality of his writing is so good, it comes as surprise to learn this was his first book. The gradual change in mood and awareness of our hero is perceptible in his descriptions and moments of reflection.

The Bradshaw we meet writes his own diary and notebook as we progress and his descent from fresh faced rookie into hardened frontline soldier sings out. There are moments when the awareness of the change in his outlook hits home, eliciting a begrudging pride in his prowess.

Bradshaw identifies the difference between men like him, products of the Derby Scheme, with later conscripts. He looks at the dwindling number of old soldiers, some of whom had been at the Battle of Festubert in 1915.

There is a chasm between them all, but they remain glued to their brotherhood of the frontline trench. Bradshaw sneers at the huge number of support troops living in comfort. The REMFs of modern parlance. However reluctant, he is part of the tip of the spear and will always be superior.

Periods of action are mixed with the misery of backbreaking labour and boredom. Bradshaw’s war is a confusion of sights, sounds and emotions.

Friends die while others are wounded and disappear from the story. Awareness of a bigger picture is scant. Some men barely know which units they are in. Senior officers are hardly seen.

This is the story of section, platoon and company level warfare populated by subalterns and captains. The protagonists are family. There is very little contact with the enemy and greater effort is expended fighting personal wars against lice and rats.

Bradshaw appears as a particular product of his age. Not particularly patriotic, not a true believer in the rights and wrongs of the war. He doesn’t drink, smoke or swear.

He loathes profanity; instead he seeks something tangible to place him outside the base instincts of his comrades. But they were all in it, together or not; and our hero seems a fair focal point for a kind of universal soldier we can all admire over a century on.

Bill Tilsley was a Mancunian by birth, he served initially with the Manchester Regiment before being re-mustered into a battalion of the Loyal North Lancashires where most of his comrades were products of the industrial towns of the north-west of England. He had enjoyed a good education by the standards of the day, which clearly shows in his writing.

After the war he went through many of the struggles of life, seeking work and trying to recover from his experiences. He married and had a son, but, very sadly, he did not live to an old age, dying in 1943.

The gentle sleight of hand Bill Tilsley used to tell his story should not detract from its abundant authenticity. His account of trench life with the 1st/4th Loyals offers as genuine a window on trench warfare and the lot of the ordinary Tommy as you will find anywhere.

This new volume is enhanced by the work of Gaye Magnall to rediscover Bill Tilsley, the man, and Bradshaw. She traces his comrades and has done an amazing job identifying them from among the cyphers in Bill’s wonderful book.

Bradshaw’s chum ‘Bagnall’ was her husband’s uncle Ernest Magnall. The book is further enhanced by an introduction from Edmund Blunden, one of the top names of contemporary Great War writing.

Another Article From Us: The Rum-Loving Monkey Who Crash-Landed in a B-17 During WW2

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

OTHER RANKS

By WV Tilsley

Uniform

ISBN: 978 1 912690 18 3