More than a dozen films have been made about him. Countless books have been penned about him and the times in which he lived. But still, no one is certain just how Rasputin died.

Both good and bad legends swirl around the Russian “priest” whose behavior certainly hastened the fall of the Czar of Russia, if not directly caused it. He was a charmer, a snake oil salesman who deluded the Romanov royal clan into believing that he could cure their son of hemophilia.

His deceit and appalling behavior led to his death at the relatively young age of 47. He died under questionable circumstances at the Imperial Palace in December 1916.

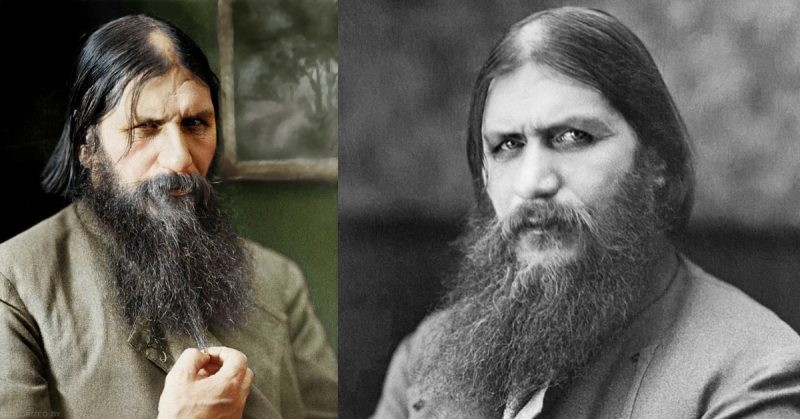

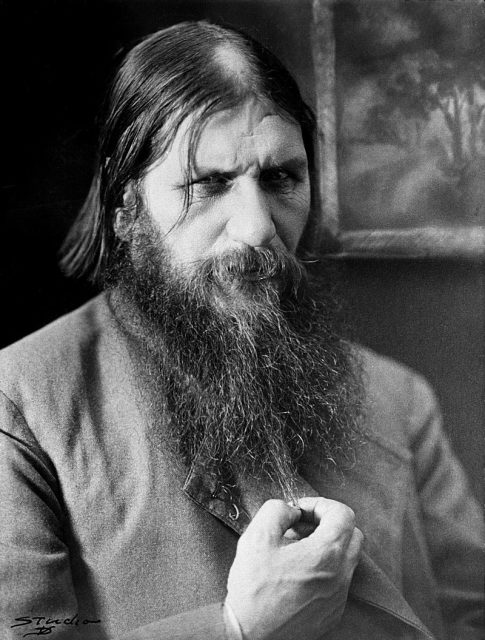

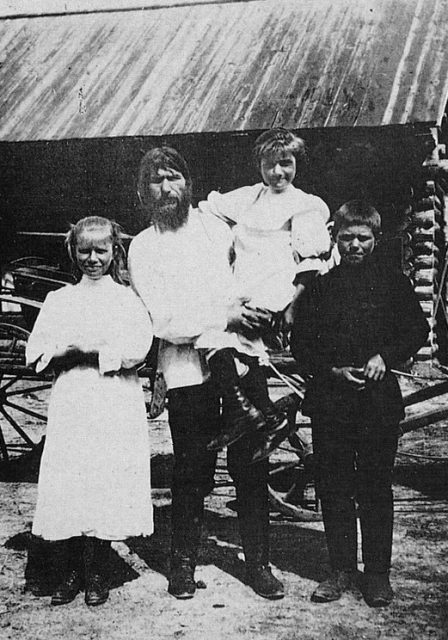

Grigori Rasputin was born in a small village in Siberia in 1869. He was a controversial character long before he began siphoning money and comfort from the Royal family.

After leaving his wife and children, Rasputin roamed around Russia for several years. He took cover in various monasteries to escape the brutal Siberian climate. In 1893, he declared he’d had a vision, and subsequently founded his own church in 1902.

Although he’d never gone through seminary school, he called himself a monk. But his “scriptures” were so bizarre that members finally expelled him. At one point, he announced that parishioners should commit sins, then seek forgiveness for them.

By 1905, he’d gone to Petrograd (now St. Petersburg) and adopted a more temperate religious doctrine.

People there were ready for someone like Rasputin, and he developed a substantial following. Opinions about Rasputin were sharply divided and never tepid. Some declared him a mystic, others said he was a charlatan.

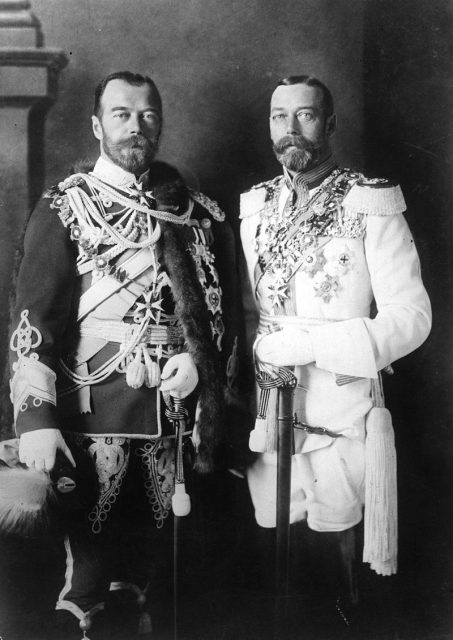

It was his claims of being a healer which brought him to the Imperial family’s doorstep. Nicholas II and his wife, Alexandra, had one son, Alexei, who became very ill at just three years old. Legend has it that Rasputin knelt at the boy’s bedside, and within a few hours, the boy had recovered.

At that moment, Rasputin had the parents in his thrall. He started exploiting their wealth and devotion to him and gained a large following among Russia’s upper class.

When the Great War broke out in 1914, Rasputin tried to dissuade Nicholas from letting Russia join, but Nicholas was determined, and even went to the front himself.

During his absence, Rasputin seized the chance to cozy up with the Empress and her inner circle even more.

He even claimed to be the true Emperor, a statement that found its way into the newspapers of the day. He was widely mocked for this and other stances, but the Royal family did not expel him from their midst.

His lectures, his so-called healing powers, and his patronage of brothels riled the government. One politician, in particular, Vladimir Purishevich, spent several hours in front of Parliament recounting Rasputin’s misdeeds, blaming him for all the country’s woes.

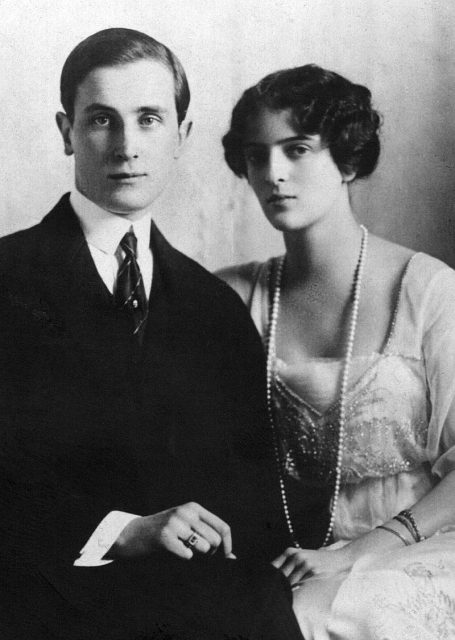

In the audience was Prince Felix Yusupov, the Czar’s nephew-in-law. He believed Rasputin had to go. Russia’s elite had watched America and France undergo drastic revolutions. Now, they feared for their safety and believed their country’s societal structures were under threat.

Felix told Rasputin that his wife, the Czar’s niece, Irina, was a chronic nymphomaniac, hoping this would lure the “mystic” to his home. The plan worked. Upon arrival, Rasputin was, legend has it, given wine and food laced with cyanide. But although he ate a great deal, the poison had no effect.

In another room, Yusupov’s co-conspirators were waiting: Vladimir Purishkevich and the Grand Duke, Nicholas Mikhailovich. The Duke grabbed a pistol and shot Rasputin in the abdomen, but even then he didn’t die.

When Rasputin tried to leave, Yusupov went after him and shot him again. Still, the “priest” didn’t die. Growing frustrated at their failures, the men beat and stabbed Rasputin, then finally tossed him into the Malaya River, where he drowned.

Rasputin had predicted that, if he died at the hands of Russia’s nobility, the Royal family would be assassinated within two years. About 18 months later, the whole family was killed by the Bolsheviks.

What should we make of Yusupov’s account of Rasputin’s death? Did he poison him to no effect, then shoot him? Yusupov’s version of events does not line up with the autopsy results, which concluded that Rasputin had been shot by two different guns and that there was no poison in his system. One of those guns matched the type used by British spies.

Many historians think that Rasputin was eliminated by Lieutenant Oswald Rayner, of the British MI6 spy agency. The monk was a target because he did not support Russia’s war efforts, and his opinion carried great weight with Czar Nicholas.

Many believe it was Rayner who fired the second, fatal shot to Grigori Rasputin, as a way of ensuring he could not persuade the Czar to withdraw Russia from the war. While it’s known that the Czar met with British officials after Rasputin’s death, what they spoke of isn’t clear.

Read another story from us: Diary Reveals Firsthand Account of Fierce Turkish-Russian Battles

What is clear is that the Russians continued to help the Allies in World War I, and that their participation went a long way toward ensuring the Allies won.

It was not just Rasputin’s attitude to the war that imperiled him. He flouted conventional mores, took advantage of nearly every woman who came within his reach, and boasted about being a “mystic” and a “healer.” Such actions were equally responsible for his fate.