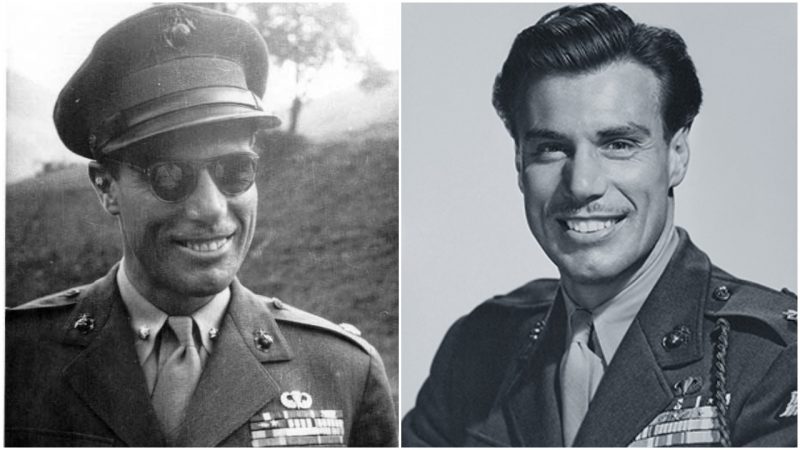

World War II had many heroes, but few had the flair and elan of Pierre Julien Ortiz, known to his friends (and his enemies) as Peter.

The New York-born Ortiz was educated in France and signed up to the French Foreign Legion in 1932 when he was just 19. He made his way through the ranks quickly, becoming first corporal then sergeant just two years later.

His bravery earned him the Croix de Guerre – twice – and also the Medaille Militaire. Although he was offered a commission and French citizenship for his services to France, he declined. He elected to return stateside in 1937.

Initially, he became an advisor on Hollywood films, giving input to producers who wanted their military-themed movies to have an aura of authenticity. But when war erupted again in 1939, Ortiz wanted to serve, so he headed back to France.

His boat was struck by the Germans, but he was picked up by a passing luxury liner. He re-enlisted in 1940.

He fought in the Battle of France in 1940 but was wounded while sabotaging a fuel station. The Germans caught him, but he escaped and was able to get back to America. When Pearl Harbor was attacked in December 1941, he was asked to serve in the CIA’s Office of Strategic Services (OSS).

While waiting to hear back from them, he chose to enlist in the United States Marine Corps (USMC) instead, in 1942. In addition to his experience and training, Ortiz spoke ten languages, including German and Arabic, making him an enormous asset to the Allies.

He was sent to the North African front. His orders were to find out all he could about the enemy – just the kind of assignment he relished.

Ortiz finally did become a member of the OSS in 1943 and fought in the Battle of Kasserine Pass.

He wasn’t slowed by an injury to his right hand and tossed hand grenades at a German vehicle to disable it. Although he had to go back to America to have surgery on his hand, Ortiz remained committed to the fight.

When the Allies began organizing Operation Overlord (Normandy), men were needed to train the French Resistance fighters. Ortiz volunteered, so he and two others were parachuted into the Rhone-Alps in early January 1944.

Over several months, the trio sabotaged rail cars, blew up patrols, and did anything else they could to inhibit the Germans’ progress. Though they staged some risky and even foolish moves, they evaded capture. His mission was halted just long enough for Ortiz to be given a Navy Cross and promoted to Major.

In August 1944, Ortiz and a crew of seven others were back in the French Alps, but this mission did not go as smoothly. The Germans were on their trail. One of the men was hurt and had to be pulled out, and another was killed during the parachute drop.

But Ortiz and his men were determined to keep morale up and even wore their Marine uniforms at all times to prove they were unafraid.

It wasn’t just the soldiers who needed their spirits lifted; civilians did, too. So one night, in a cafe packed with soldiers and civilians alike, Ortiz pulled a stunt that would make him famous until the end of his days.

This particular cafe was teeming with German soldiers, all of them uttering their distaste for the war and how their country was faring. It was also filled with ordinary French folks who were depressed about the fighting in which their country was mired.

Suddenly, the Germans fell silent. A man had stood up, taken off his coat, and revealed a U.S. Marine uniform. A 45 caliber pistol was pointed straight at them. The man ordered the German men to make a toast to the American president, Theodore Roosevelt, and they complied – they had no choice.

Pushing his luck, Ortiz then insisted on another toast, this time to the U.S. Marines. Once again, the Germans obeyed. The “mystery man” bowed in a grand, sweeping gesture, and before his audience could react, he was gone.

Ortiz was known to the locals, but stunts like that rapidly made him a legend. Yet his grandest stunt still lay ahead, on August 16. He and his men were making their way through a small village called Centron. It was here that they were attacked by a German unit.

Wildly inflating the number of men he had, Ortiz told the Germans that he would quietly surrender his “entire garrison” if the Germans would just let the townspeople live. Miraculously, they agreed, and Ortiz was sent to a German prisoner of war (POW) camp while the town was spared.

In the spring of 1945, not long before the war was formally over, he and three other men escaped.

In spite of all Ortiz had done and witnessed throughout the war, when he got home, he offered to go and fight the Japanese in the Pacific. Before he could do so, the Japanese surrendered.

Read another story from us: How France Fell to the Nazi Invaders

In addition to the medals he earned in France, Ortiz earned two Purple Hearts, the Order of the British Empire, and many other honors.

Once settled stateside, he resumed his career as an advisor to movie producers. If anyone could guide Hollywood movie makers about what really happened during World War II, and how to make it all seem like a grand adventure, it was Pierre (Peter) Ortiz.