There is a fine line between acts of bravery and acts of madness, and there are no better examples of balancing on that line than the men who served in World War II. Whether on the ground, at sea or in the air, the challenges of war were constant and often life-threatening.

James Allen Ward was a Royal New Zealand Air Force (RNZAF) pilot in the war, and there is no finer example of the gallantry and “daring do” demonstrated by so many of those who served. He was only 22 years old when he undertook an action that his superiors dubbed heroic, but that his mother undoubtedly would have dubbed insane.

Born in New Zealand and educated to be a teacher before the war, Ward was stationed at Lossiemouth, Scotland’s air base, after he joined the RNZAF. Approximately six months after he arrived, he and his crew were ordered on a raid against Munster, Germany.

Ward – who lived to tell this tale – said that the raid itself went very smoothly. The Germans mounted little in the way of a counter attack, so the men dropped their bombs as instructed, and headed for home.

Then things took a sudden turn for the worse–much, much worse.

Not only was an enemy plane on the tail of their Wellington bomber, but the plane’s intercom system also chose that moment to cut out. Ward could not alert his comrades to the looming threat. The Germans opened fire, and the plane went into a stomach-lurching nose dive.

Fortunately for Ward and his crew, the rear gunner was able to dispatch the German plane, but at the time he had no way of communicating that to the others. A silent, black comedy of problems ensued.

During the attack, the Wellington had taken a hit–its hydraulics were crippled, and half the undercarriage was so torn it couldn’t be used for landing. Worst of all, the gas feed pipe was damaged, causing a fire on the starboard wing.

The men readied their parachutes. Reaching the fire with an extinguisher had proved impossible, so it seemed the crew had little choice but to bail out. Unanimously, they decided to wait until they were over the open sea, as none wished to crash on land and become prisoners of war in Germany.

That is when Ward, either bravely or stupidly, depending on how one views risk, decided to gamble with his life.

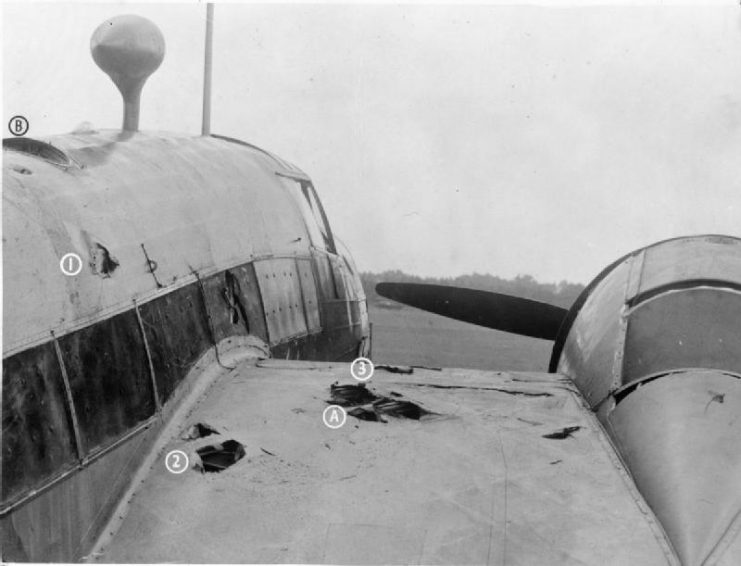

After tying a rope around his waist that the others then clung to, Ward climbed out the top hatch of the plane. Punching holes in the side and wing of the plane in order to hold on against the force of the powerful air stream, he worked his way over to the fire in the wing fabric and managed to smother it.

With help of the others, Ward then made it back into the plane safely, but barely, and was no doubt shaken up. With the fire extinguished, the crew was able to get the plane back to base.

Ward told his superiors precisely what had happened. At first, they scolded him instead of rewarding him, saying he took too much risk with his own life, and the lives of his comrades. Ironically, military leaders preferred giving the Victoria Cross to men who died during operations while saving others. But cooler heads prevailed, and finally Ward was indeed awarded the V.C. for his bravery.

War is a cruel and unpredictable game of chess, and it wasn’t finished with James Ward. On his 11th mission, his fifth as captain, his plane crashed near Hamburg. Two men did survive, but Ward did not. His luck, though not his bravery, had run out.