Officials from Navajo Nation confirmed recently that native American code talker Alfred K Newman has died aged 94.

He had served from 1943-45 in the 1st Battalion of the 21st Marine Regiment and 3rd Marine Division. He was one of many Navajo men who used a code based on the Navajo language to out-wit the Japanese. Newman saw service in Guam, Iwo Jima, Kwajalein Atoll, Enewetek Atoll, New Georgia, and New Caledonia.

It may seem strange that the native Americans, whose situation and ambitions appeared to be at odds with those of the European settlers, would be ready to take up arms alongside their former foes. However, the warrior tradition has long been a deep and significant part of Native American culture, where protection of the needs of the tribe take a central role.

For many American Indians, life in the military offered some financial security and opportunities for education, training, and travel. During WWI, more than 12,000 American Indians, a quarter of the adult male population, served in Europe.

Later, during World War II, when Alfred K Newman enlisted, he served alongside an estimated 44,000 First Nation men and women.

Code talking began in the US Army in World War One with Choctaw and other American Indians sending messages over the telephone in their native tongues. Although code talking was not used extensively, it was credited with helping the US Army to win a number of key battles.

At the beginning of 1940, the US forces set out once again to recruit native American speakers to transmit and receive messages. Using specialist trained American Indian army officers, they began by recruiting Choctaws and Comanches, Hopis and Cherokees.

Philip Johnston was a World War One veteran who had grown up on a Navajo reservation. While Johnston was not a Navajo, he had heard of the successes of the Choctaw Telephone Squad and so set about convincing the Marine Corps that the Navajos and others would be ideal for the same essential roles in the unfolding crisis of 1941.

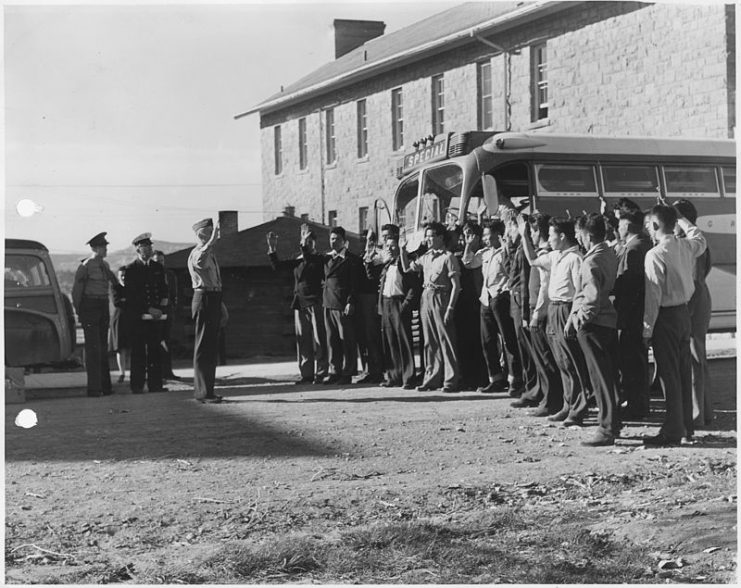

A demonstration was set up, and within two weeks, the Marine Corps had signed up 29 Navajo warriors. A specialized Navajo Code was developed, and a training school was set up.

As the war went on, more than 400 Navajo code talkers were recruited and trained. After Basic Training they progressed through Code School where they were expected to memorize the codes and communication skills.

For many code talkers, it was simply a case of using every day tribal language, known as Type Two codes. The Navajos and others developed things a little further. The Navajo Type One code was developed by the first 29 recruits who used a Navajo word for each letter of the English alphabet.

For example, the letter C was sent as “Moasi,” the Navajo for “Cat.” The letter D was sent as “Lha-Cha-Eh,” the Navajo for “Dog,” and so on. There were also specific code words for military hardware, ordnance, etc, such as, “Atsá” the Navajo for “Eagle,” which was used to refer to transport planes.

The code talkers became an essential and integral part of the war in the Pacific, simply by referencing the natural world that filled the Navajo tradition of songs and stories. Their remarkable memories were a result of generations of absorbing an oral tradition that was recorded nowhere else.

Read another story from us: Marines’ Secret Weapon in the Pacific: Navajo Code Talkers

Navajo code talker Carl Gorman explained it this way: “For us, everything is memory, it’s part of our heritage. We have no written language. Our songs, our prayers, our stories, they’re all handed down from grandfather to father to children—and we listen, we hear, we learn to remember everything. It’s part of our training.”